(Reproduced with permission by the author, Clyde Durham; Dec 1, 2007)

At 1000 hours Sunday,

25 June 50, Far East Air Force Headquarters received word of the North

Korean attack on South Korea.

About six hours earlier the North Koreans had slashed across the 38th

parallel and the South Koreans were being totally routed.

That afternoon the United States Air Force was at war again. President

Truman ordered Gen. Douglas MacArthur to send the Air Force and the Navy

to battle.

First USAF bombers on the offensive were 12 Douglas B-26 attack bombers

from the 8th Bomb Squadron. They hit rail yards at Musan early on the

28th of June. That same afternoon four B-29s from the 19th Bomb Group

out of Kadena Air Force Base on Okinawa hit roads and railroads just north

of Seoul. (Mick's note: please forgive the author for referring to KAB as "Kadena Air FORCE Base" - as you may know, U.S. Air Force facilities not on U.S. soil are "Air Base" and not "Air Force Base).

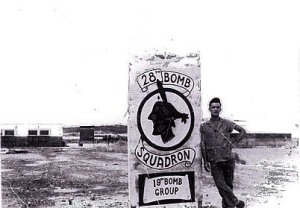

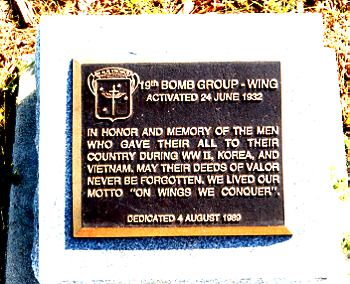

The 19th BG was made

up of the 28th, 30th and 93rd Bomb Squadrons and was permanently based

at Andersen AFB, Guam. Less than 24 hours after being alerted, the 19th

BG was at Kadena and preparing for their, first combat mission over Korea.

They had been told to take enough clothing and personal items for " a

few weeks." No one dreamed that 37 months later the 19th would still be

at Kadena, the only one of the three original B-29 bomb groups to fly

combat for the entire war.

As the war began, in addition to FEAF's 19th, SAC sent the 22 "d and 92"d

Bomb Groups, also equipped with B-29s.

In May of 1952 the three B-29 groups flying combat were two at Kadena,

the 19th and SAC's 307th and the 98th, also SAC, which was based at Yakota

AFB near Tokyo.

That same month a replacement crew, headed by Aircraft Commander Capt.

H.M. Locker, prepared to fly from California to Kadena AFB, reporting

for a tour of duty with the 28th Bomb Squadron. I was the left gunner

on that crew.

We had orders to fly a re-conditioned B-29 from McClellan AFB to Kadena

but after waiting 10 days with no plane being ready, our orders sent us

to Travis AFB and a day later we left on a C-54 ambulance aircraft that

shuttled between Korea and the states. They flew wounded GIs home and

returned to the Far East with replacement personnel.

We spent about 24 hours at Hickam AFB in Honolulu, then made the remainder

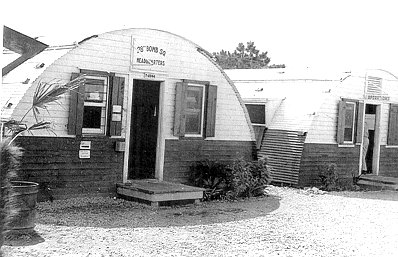

of the trip in a couple of hops. After reporting in at 2e Bomb Squadron

headquarters, we were assigned barracks, flight gear and attended orientation.

This all took the better part of a week and then we began flying training

missions. The training included very little formation flying, which was

unexpected by us, but was long on navigation and radar bombing using SHORAN

as well as LORAN. We soon were told why.

Up until a few months prior to our arrival, most B-29 missions were during

the daylight hours, but now that the Chinese Communists were into the

war their better experienced MiG- 15 pilots were really beginning to take

a toll on B-29s. On one mission a few months before we got there, we were

told that on one five-plane B-29 raid, four of them were lost to MiGs.

As a result strategy was changed and now we were flying almost 100% of

our combat missions at night. In fact the undersides of less than half

our B-29s had been painted black. It wasn't until after we had flow four

or five missions that all the B-29s at Kadena had been coated with black

paint on their undersides.

After flying the orientation training missions we were cleared for combat

and told that our first mission would probably be in the next three or

four days.

The procedure in the 28th was to post the names of crew members and their

aircraft on the bulletin boards in the barracks daily for the following

nights mission. This was done about 24 to 28 hours prior to scheduled

takeoff.

Since we knew we would soon be on a mission we were joking about flying

it on Friday, the 13th! On Thursday afternoon, 12 June 52, word quickly

spread that Friday's combat roster had been posted.

A friend stuck his head in my room, we were bunked two to a room, and

told me my name was on the list. I made a fast trip to see for myself

and there it was! It was as though my name was typed in inch-high capital

letters and highlighted with a spotlight.

I'm sure my heart paused for a few seconds. My first combat mission and

on a Friday, the 13th!

As was the custom, crew members on their 'first" combat mission were flown

as extras or replacements on a veteran crew. Not until the second or third

mission did a new crew fly as a unit together. With us it was our second

mission that we flew as a crew with only an experienced pilot as observer.

It was on a B-29 named `.`Island Queen".