| This site offers background and a bibliography of recent and historical articles and writings on tobacco-induced brain damage.

This site assists in the "rediscovery" of "tobacco use as a mental disorder" (see citation below).

This is not initial discovery, this is rediscovery: data that used to be widely known, but became subjected to the tobacco taboo (meaning, censorship, suppression, treating this data as 'unmentionable.'

The tobacco taboo is still not overcome. You can observe that most all writers on the subject perversely insist on calling tobacco use (meaning, addiction, mental disorders, and brain damage), a mere 'habit.' (In law, the

universal malice intent of such writers is foreseeable harm, as shown by the typical natural and probable consequences of the censorship and suppression of this data, obstructing public awareness, limiting meaningful awareness to the research community.)

Tobacco Smoke is properly identified as Toxic Tobacco Smoke (TTS). It is produced by Tobacco Smoking Conduct (TSC). The TTS chemical combination is not environment-, but conduct-generated.

TTS has high quantities of

carbon monoxide (42,000 particles). Carbon monoxide is unsafe in quantities above 100 particles. See our site on cigarettes' toxic chemicals.

The brain requires an unobstructed blood flow and operates on electrical impulses and chemicals, e.g., serotonin, dopamine, endorphins, etc. They are involved in regulating mood, reasoning, ethical controls, and all brain functions. The brain's message transfer process involves individual brain cells, neurons, passing messages from one neuron to the next. Neurons communicate with each other by using such chemicals to transfer messages, cross the synapses, between neurons.

Tobacco's massive quantities of toxic chemicals have an impairing effect on this message transfer process. Tobacco alters, impairs, damages, brain function and structure.

Naturally the foreseeable result is that brain functions (e.g., mood, reasoning, ethical controls, the self-defense function, arithmetic abilities, verbal skills, thought and sentence formulation, etc.) are impaired, paralyzed, damaged, altered, destroyed. Tobacco is, in short, what may be deemed a "mind-altering drug," a "narcotic."

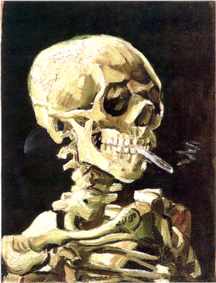

Tobacco causes brain damage. The role of tobacco in damaging brain function and structure is ancient medical knowledge, long known. This site provides you background on this long known medical knowledge.

TTS-caused damage, says Thomas Edison (26 April 1914) is irreversible.

It is said that tobacco relieves stress, relaxes. Here is why: The massive quantities (42,000 ppm) of carbon monoxide that tobacco smoke contains, result in an impaired oxygen supply to the brain. This is "cerebral anoxia." It occurs cell by cell, neuron by neuron, year after year. When to any cell, neuron,

"the oxygen supply is cut off, then damage to neurones occurs after a few minutes. Some neurones die."—Anthony Hopkins, Epilepsy: The Facts (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1981).

Dead brain cells, dead neurons, are quiet, calm, "content," "soothed," "relaxed," "

pleasured" cells, i.e., an "euphoric effect "! Thus tobacco-users face enormous dangers without

seemingly caring! The brain damage (e.g., dyscalculia and anosognosia) they develop, means that they cannot compute the odds against them, odds that nonsmokers around them easily grasp!

Cigarette smoke's toxic chemicals including carbon monoxide cause brain damage that alters motor control function and short term memory. In essence, smokers short circuit their own learning process. This presents to the smoker as if it were a 'calming' effect, as adult learning produces anxiety to the emotional platform. Smoker behaviors are seemingly impossible to change as there can be little or no learning process while undergoing continual brain damage.

For data on what people used to be taught about tobacco's adverse brain effects, click here.

For why this data is no longer taught, click here and here. |

Additionally, cigarette smoke is quite radioactive, says E. A. Martell, "Tobacco Radioactivity and Cancer in Smokers," 63 American Scientist 404-412 (July-August 1975). Radioactivity renders artery walls "highly permeable to the passage of red cells [bleeding]."

That fact helps explain what was described about smokers a century ago:"Autopsies have revealed large foci of softening in the brain, hemorrhages into the meninges, and capillary apoplexies [small strokes] in the brain substance."—George W. Jacoby, M.D., 50 N Y Med J 172 (17 Aug 1889) [Details].

Also, "Ecchymosis occurs in the pleura and peritoneum. Hyperemia of the lungs, brain, and cord is found. . . . Coarse lesions have been found in the brain and spinal cord."—Leon Pierce Clarke, M.D., 71 Med Rec (#26) 1072-1073, at 1073 (29 June 1907). [Details].

This combination of brain damage effects foreseeably, as a "natural and probable consequence," leads to addiction and DSM-III conditions, and organic conditions such as 'small strokes,' affecting millions annually, silently, and having cumulative effects. It is addiction, aka tobacco-caused brain damage, that keeps so many smokers smoking, due to impairing the self-defense reflex, and causing related brain injuries.

Thus, conditions such as “mental disease . . . fall into [the] predictability category," say Drs. C. J. Zook and Dr. F. D. Moore in "High-cost users of medical care," 302 New Engl. J. of Med. (# 18) 996-1002 at p 1001 (1 May 1980).

This site has some of the many findings on tobacco-caused brain damage.

"The pharmacology of nicotine [C10H14N2] has been carefully studied . . . in analyzing the autonomic nervous system. [It] is a potent and rapid acting poison . . . a vast literature on this alkaloid has accumulated since its discovery in 1828."—W. Kalow, M.D., Professor of Pharmacology, University of Toronto, "Some Aspects of the Pharmacology of Nicotine," 4 Applied Therapeutics (#10) 930-932 (Oct 1962).

"Tobacco is, in fact, an absolute poison."—Journal of Health, Vol 1 (Philadelphia, 1829).

"Avant le . . . tabac, la folie était une maladie très rare dans l'humanité,"—Hippolyte A. Depierris, M.D., Physiologie Sociale: Le Tabac (Paris: Dentu, 1876), p 346. Before tobacco, insanity (brain damage) was a very rare malady among humans.

Saying likewise were Emile Seutin and Louis Joseph Ghislain Seutin, Le tabac: Étude sur les dangers inhérents à l'abus du tabac (Bruxelles: Mertens, 1890),

p 105.

See also

"Your Brain on Drugs" (April 2013), and a Surgeon-General type overview of tobacco effects published by Rev. John B. Wight, Tobacco: Its Use and Abuse (Columbia, South Carolina: L. L. Pickett Pub Co, 1889), pp 72-73, "in exact proportion with the increased consumption of tobacco is the increase of diseases in the nervous centers—insanity . . . frightfully increasing . . . in proportion to the increase in the use of tobacco."

Overview of Medical Writings on Tobacco and Brain Damage

in Reverse Chronological Order (Most Recent - Longest Ago)

173. Drs. Raj Persaud and Peter Bruggen, "Cigarette Smoking 'Could Make You Psychotic'" (11 November 2013) ("This latest investigation from researchers at University Medical Centre Utrecht, The Netherlands, and the Institute of Psychiatry, London, was partly inspired by the well-known observation that [the vast] majority (as much as 70-85%) of patients with schizophrenia smoke cigarettes. Within academic medicine the association between cannabis use and psychotic symptoms is firmly established. . . . previous research has found nicotine dependency is associated with psychotic symptoms. The more you smoked when young the more likely you are to develop psychotic symptoms later in life. Other research has independently established an association between cigarette smoking and psychosis.")

172. SAMSHA, "Adults experiencing mental illness or a substance use disorder account for nearly 40 percent of all cigarettes smoked" (20 March 2013) ("the rate of current cigarette smoking among adults experiencing mental illness or substance use disorders is 94 percent higher than among adults without these disorders.")

171. Alex Dregan, Robert Stewart and

Martin C. Gulliford, "Smoking 'rots' brain, says King's College study" (BBC, 25 November 2012) ("Smoking "rots" the brain by damaging memory, learning and reasoning, according to researchers at King's College London," citing Age and Aging, Oxford University Press.)

170. Rachel Whitmer, et al., "Heavy smokers 'at increased risk of dementia'" (BBC, 25 October 2012) ("Heavy smokers with a 40-a-day [addiction] face a much higher risk of two common forms of dementia . . . . The risk of Alzheimer's is more than doubled in people smoking at least two packs of cigarettes a day in their mid-life. The risk of vascular dementia, linked to problems in blood vessels supplying the brain, also rose significantly," citing Archives of Internal Medicine)

169. "Male smokers lose brain function faster as they age" (7 February 2012) ("who smoke suffer a more rapid decline in brain function as they age than their non-smoking counterparts, with their cognitive decline as rapid as someone 10 years older but who shuns tobacco . . . with early dementia-like cognitive difficulties showing up as early as the age of 45.")

168. Kühn, S.; Schubert, F.; Gallinat, J.: "Reduced thickness in medial orbitofrontal cortex in smokers," Biological Psychiatry (25 September 2010), cited by Florian Schubert, Ph.D., "The more someone smokes, the smaller the number of gray cells: Scientists of the Charite Berlin and of PTB confirm: Smokers have a thinner cerebral cortex" (28 October 2010) (the study "showed that in the case of smokers, the thickness of the medial orbito-frontal cortex is, on average, smaller than in the case of people who have never smoked.")

167. Rachel Whitmer, M.D., et al., "Heavy smokers 'at increased risk of dementia'" (BBC, 25 October 2010), in Archives of Internal Medicine ("The risk of Alzheimer's is more than doubled in people smoking at least two packs of cigarettes a day in their mid-life. The risk of vascular dementia, linked to problems in blood vessels supplying the brain, also rose significantly. . . . among those currently smoking two or more packs, equivalent to 40 or more cigarettes a day, there was a 157% increase in the risk of Alzheimer's disease. There was also a 172% increase in vascular dementia risk compared to someone who had never smoked.")

166. Paul Bentley, "Is this proof smoking lowers your IQ? Study suggests those on 20 a day are less intelligent" (30 March 2010) ("averaged an IQ seven points lower than non-smokers . . . markedly lower intelligence levels"). See also "Smoking Is Dumb: Young Men Who Smoke Have Lower IQs, Study Finds" (Science Daily, April 2010).

165. Wiley - Blackwell, "Smoking Linked To Brain Damage" (ScienceDaily, 23 June 2009)

(citing "a direct link between smoking and brain damage. . . . a compound in tobacco provokes white blood cells in the central nervous system to attack healthy cells, leading to severe neurological damage.")

164. Rita Machaalani, "First direct link of passive smoking to cot death" (22 April 2009) (Data shows that "more brain cells in the part of the brain responsible for vital functions like breathing and blood circulation had died in babies that succumbed to SIDS." Result: "81 per cent of the infants who died of SIDS had been exposed to cigarette smoke, while only 58 per cent of those who died of other causes were exposed to second-hand smoke."

163. Astrid C.J. Nooyens, Boukje M. van Gelder, W.M. Monique Verschuren, "Smoking and Cognitive Decline Among Middle-Aged Men and Women: The Doetinchem Cohort Study" (American Journal of Public Health, 15 October 2008, 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130294)

(Summary: "smokers scored lower than never smokers in global cognitive function, speed, and flexibility; at the five-year follow-up, decline among smokers was 1.9 times greater for memory function, 2.4 times greater for cognitive flexibility, and 1.7 times greater for global cognitive function than among never smokers.")

162. Jonathan D. Pendlebury, et al., "Respiratory Control in Neonatal Rats Exposed to Prenatal Cigarette Smoke," American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Vol. 177, pp 1255-1261 (28 February 2008) ("The toxins in cigarette smoke cross the placenta and collect in the fetus," says Shabih U. Hasan, M.D., a pediatrician from the University of Calgary, Canada, cited in the article, "Damage From Smoking Can Start Before Birth" (10 June 2008). These toxins are "transmitted to the fetus, and all the carcinogens of cigarette smoke cross over to . . . the fetus very, very quickly and remain there in a much higher amount than on the other side," Hasan explains. "One speculation is that when you give carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide through smoke, it changes [damages] the brain's receptors and it probably changes probably the baby's ability to sense oxygen so that they cannot sense it, or some other changes happen.")

161. CASA, "Teen Cigarette Smoking Linked to Brain Damage, Alcohol and Illegal Drug Abuse, Mental Illness" (23 October 2007) ("The nicotine in tobacco products poses a significant danger of structural and chemical changes in developing brains that can make teens more vulnerable to alcohol and other drug addiction and to mental illness.")

160. Dr. Monique Breteler, of Erasmus Medical Center, "Smokers more likely to develop dementia" (Science News, 4 September 2007; Neurology) ("people who smoke are more likely to develop Alzheimer's disease or dementia than non-smokers or those who smoked in the past." "Smoking increases the risk of cerebrovascular disease, which is also tied to dementia." And reference "oxidative stress, which can damage cells in the blood vessels and lead to hardening of the arteries. Smokers experience greater oxidative stress than non-smokers, and increased oxidative stress is also seen in Alzheimer's disease.")

159. Kaarin J. Anstey, Chwee von Sanden, Agus Salim and Richard O'Kearney, "Smoking as a Risk Factor for Dementia and Cognitive Decline: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies, 166 American Journal of Epidemiology (#4) 367-378 (14 June 2007) ("elderly smokers have increased risks of dementia and cognitive decline").

158. Bruce Hope, et al., “Nicotine, Other Drugs Have Similar Brain Effects” (Journal of Neuroscience, 21 February 2007) (“The long-term brain changes observed among cocaine and heroin users can also be found in the brains of smokers, researchers from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) say. . . . changes to smokers' brains could be observed even years after they quit . . . abnormally high levels of a pair of enzymes involved in the dopamine system . . . changes . . . the same among smokers as among other drug users”).

157. Jennifer W. Tidey, Damaris J. Rohsenow, Gary B. Kaplan and Robert M. Swift, “Cigarette smoking topography in smokers with schizophrenia and matched non-psychiatric controls,” 80 Drug and Alcohol Dependence

(# 2) 259-265 (1 Nov 2005) ("Smoking is highly prevalent among people with schizophrenia . . . findings suggest that smokers with schizophrenia smoke more intensely than matched non-psychiatric smokers." (This is a dose-response factor, typical of causation.)

156. Jennifer Glass, Ph.D., "Long-Term Smokers Suffer Lowered IQs" ("Long-term smoking hinders mental speed and accuracy, according to a new study that finds that chronic smokers experience a decline in their IQ scores") (See details in Medical World News (11 Oct 2005) and Drug and Alcohol Dependence (Oct 2005)

155. "Smoking ‘seriously damages your IQ’," by Camillo Fracassini, London Times (5 December 2004), citing L.J. Whalley, H.C. Fox, J.J. Deary, John M. Starr, "Childhood IQ, Smoking and Cognitive Change from Age 11 to 64 Years," in Addictive Behaviors (Dec 2004) [More].

154. Bruce Parker, M.D., "Urban Legends" Letter, 50 Car and Driver (Issue #4) p 22 (October 2004) ("I . . . firmly believe that smoking damages one's thinking ability, leading to this type error." He wrote this in context of smokers' addiction, of an emergency room incident he covered, caused by the lighting of a cigarette lighter "to see much fuel was left in the 55-gallon drum at hand." The fuel center owner was burned over 90% of body, and thus died. This is one of a number of such incidents, e.g., the McAfee and Travis incidents, among many tobacco-use-caused fires.)

153. Belluzzi, Prof. James, Frances Leslie, et al., "Tobacco Research Center Study Suggests First Exposure To Nicotine May Change Adolescents' Brain And Behavior," Psychopharmacology (13 May 2004) (News Release; the study cites "rapid changes in the brain and behavior of adolescents after just a single administration of nicotine")

152. Ott, Prof. Alewijn, K. Andersen, M. E. Dewey, L. Letenneur, C. Brayne, J. R.M. Copeland, J.-F. Dartigues, P. Kragh–Sorensen, A. Lobo, J. M. Martinez–Lage, T. Stijnen, A. Hofman, and L. J. Launer, "Effect of smoking on global cognitive function in nondemented elderly," 62 Neurology (#6) 920-924 (23 March 2004), reported as "Smokers suffer faster mental decline" (22 March 2004) (smokers have "a markedly faster mental decline" and "lose their mental faculties up to five times faster than non-smokers" "including the onset of atherosclerosis and hypertension caused by tobacco use" and thus "increased the risk of stroke and 'silent' brain infarctions")

151. Harvey, John, M.D., "Smoking diseases alter the brain," Metabolic Brain Disease (reaction of brain "functions in response to a poor oxygen supply . . . emphasises the dramatic widespread nature of the damage that cigarettes can wreak on the body.")

150. Abrous, D. N., W. Adriani, M. F. Montaron, C. Aurousseau, G. Rougon, M. Le Moal, and P.V. Piazza, "Nicotine self-administration impairs hippocampal plasticity," 22 J Neurosci (#9) 3656-3662 (1 May 2002) (BBC summary as "smoking 'kills brain cells'")

149. Crocker, Ann, Prof, "Most People With Schizophrenia Smoke Tobacco, says Research (9 April 2001) ("Eighty per cent of people with schizophrenia smoke tobacco, according to research."

148. Barry Bittmann, M.D., Depression and Brain Damage: 2 more reasons not to smoke" (November 2000), says, "nicotine not only has a depressive effect on the central nervous system, it also causes degeneration in a brain region that affects emotional control, sexual arousal, sleep and seizures." Such "data heralds severe mental health consequences for our nation."

147. Ellison, Gaylord, Neuroscientist, UCLA, says, "Nicotine causes the most selective degeneration to the brain I have ever seen.” (Neuropharmacology, November 2000).

146. Goodman, Dr. Elizabeth, Pediatrics (October 2000), correlated smoking and an increased rate of depression.

145. DiFranza, Joseph, M.D., of the University of Massachusetts School of Medicine, in the British Medical Association journal, Tobacco Control (September 2000), found "that [smoker] children were experiencing the same symptoms of nicotine addiction as adults who smoked heavily---even those kids who only smoked a few cigarettes a week.”

144. Baker, Lois, "Smoking increases risk for brain aneurysms," 31 University at Buffalo Reporter (#22) (2 March 2000) ("UB study finds that smoking leads to growth of large blood-vessel malformations.")

143. "Science Tobacco & You (Brain Damage)" (1 March 1999), says, "Blood vessels that supply the brain with needed oxygen and other nutrients can be damaged by chemicals found in tobacco products."

142. Gamberino, William C; Gold, Mark S., "Neurobiology of Tobacco Smoking and Other Addictive Disorders," 22 The Psychiatric Clinics of North America (#2) 301 (1999). This article discusses advances in research of the neurobiology of addictive disorders have provided clinicians with an evolving perspective on addiction. It focuses on several aspects of the neurobiology of addictive disorders, including the concept of brain reward, mechanism of action, and cellular and molecular aspects of drug addiction.

141. Aronow, Wilbert S; Ahn, Chul; Gutstein, Hal, "BRIEF REPORTS - Risk Factors for New Atherothrombotic Brain Infarction in Older African-American Men and Women," 83 Am J Cardiology (#7) 1144 (1999). This article cites independent risk factors for new atherothrombotic brain infarction (ABI) in older African-American men were hypertension (risk ratio 4.381), diabetes mellitus (risk ratio 2.872), and previous ABI (risk ratio 1.904). Independent risk factors for new coronary events in older African-American women were cigarette smoking (risk ratio 2.754), hypertension (risk ratio 5.914), diabetes mellitus (risk ratio 3.464), serum total cholesterol (risk ratio 1.008), serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (inverse association) (risk ratio 0.958), age (risk ratio 1.026), and previous ABI (risk ratio 2.601)

140. Launer, Lenore, 'Mental Abilities Decline Report at Am Academy of Neurology' (May 1998) (smoking in decline of mental abilities context, including memory and cognitive impairment, note damage to arteries to the brain, impairing blow flow) [cited by Damaris Christensen, Medical Tribune]

139. Fukuda, Hitoshi; Kitani, Mitsuhiro; Omodani, Hiroki, "99mTc-HMPAO Brain SPECT Imaging in a Case of Repeated Syncopal Episodes Associated With Smoking," 28 Stroke (#7) 1461 (1997)

138. Breese, Charles R; Marks, Michael J; Logel, Judy; Adams, Cathy E; Sullivan, Bernadette; Collins, Allan C; Leonard, Sherry, "Effect of Smoking History on (3H)Nicotine Binding in Human Postmortem Brain," 282 J Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (#1) 7 (1997)

137. Elwan, O; Hassan, A. A. H.; Naseer, M. Abdel; Elwan, F.; Deif, R.; Serafy, O El; Banhawy, E El; Fatatry, M El, "Brain aging in a sample of normal Egyptians' cognition, education, addiction and smoking," 148 J Neurological Sciences(#1) 79 (1997)

136. Malizia, A. L., "Brain Imaging of Nicotine and Tobacco Smoking (ed. Edward E. Domino)," 11 J Psychopharmacology(#4) 396 (1997) (Oxford, England)

135. "Does smoking marijuana prime the brain for addiction to heroin?" New Scientist (# 2089) 4 (1997)

134. Thom Hartmann, Attention Deficit Disorder: A Different Perception (1997), Chapter 11, pages 101-109 ("nicotine is one of the most powerful drugs we know of to affect the central nervous system (CNS). It's wildly more powerful than amphetamine or Ritalin, for example," p 103)

133. Fukuda, Hitoshi; Kitani, Mitsuhiro, "Cigarette Smoking Is Correlated With the Periventricular Hyperintensity Grade on Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging," 27 Stroke (#4) 645 (1996)

133. Iversen, Leslie L, "Smoking: . . . harmful to the brain," 382 Nature (# 6588) 206 (1996)

131. Filippini, G.; Farinotti, M.; Lovicu, G.; Maisonneuve, P., "Mothers' active and passive smoking during pregnancy and risk of brain tumours in children," 57 Intern'l J Cancer. J intern'l du cancer (#6) 769 (1994)

130. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders (World Health Organization, 1993), pp 8 (F17.), 55 (F17.0) and 61 (F17.3), referencing pp 48 (F1x.0), 49, and 58 (F1x.3) (on smoking as organic mental disorder)

129. Gold, Ellen B.; Leviton, Alan; Lopez, Ricardo; Gilles, Floyd H.; Hedley-Whyte, E. Tessa, "Parental Smoking and Risk of Childhood Brain Tumors," 137 Am J Epidemiology (#6) 620 (15 March 1993)

128. Glassman, A, "Cigarette Smoking and Implications for Psychiatric Illness," 150 Am J Psychiatry (#4) 546-553 (1993) (74% of schizophrenics smoke, whereas only 25% of the general population does) (See background)

127. Klein, C.; Andresen, B.; Thom, E., "Blinking, Alpha Brain Waves and Smoking in Schizophrenia," 37 Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica (#3) 172 (March 1993)

126. Kitch, D, "Editorial: Where There's Smoke . . . Nicotine and Psychiatric Disorders," 30 Biol Psychiatry 107-108 (1991) (among smokers, the most common mental disorder is schizophrenia; smokers are disproportionately mentally ill significantly more than nonsmokers)

The book, Schizophrenia: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments (New York: Norton] 1979), by Kayla Bernhein, Ph.D., and Richard Lewine, Ph.D., elaborates. At 23, “One of the defining characteristics of schizophrenia is disorganized thinking.” At 25, “More fundamentally. the schizophrenic finds it difficult to organize thoughts and direct them toward a goal. It appears as if associations lose their logical continuity. . . . This sort of disturbed [unstable] thinking is called ‘loose associations.” “[Prof. Paul Eugen] Bleuler [M.D., 1857-1939], whose turn-of-the-century characterization of schizophrenic symptoms remains unsurpassed, describes the disorder this way:

| ‘In the normal thinking process, the numerous actual and latent images combine to determine each association. In schizophrenia, however, single images or whole combinations may be rendered ineffective, in an apparently haphazard fashion. Instead, thinking operates with ideas and concepts which have no, or a completely insufficient, connection with the main idea and should therefore be excluded from the thought-process. The result is that thinking becomes confused, bizarre, incorrect, abrupt.’” |

At 126, “Thus, thoughts may be connected simply because they occur together in time. For instance, if one asks a patient a question, he may respond with an idea he happened to have at the time, with little reference to the meaning of the question. . . . Fragments of thoughts may lead to other fragments of thoughts so that, before long the original intent of the communication is lost. Our example of the schizophrenic’s response . . . is bizarre, not because the associations are bizarre but because the original goal is lost while one thought leads to another. It is as if thinking gets waylaid, leading forever down divergent paths and either failing to get to the point quickly or going beyond it. A schizophrenic patient describes the state this way:

| 'My thoughts get all jumbled up. I start thinking or talking about something but I never get there. Instead, I wander off in the wrong direction and get caught up with all sorts of different things that may be connected with the thing I want to say but in a way I can't explain. . . .

‘My trouble is that I've got too many thoughts. You might think about something, let's say that ashtray and just think, oh! yes, that's for putting my cigarette in, but I would think of a dozen different things connected with it at the same time.’” |

|

125. Knott, V. J., "Effects of Cigarette Smoking on Subjective and Brain Evoked Responses to Electrical Pain Stimulation," 35 Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior (# 2) 341 (1990)

124. Knott, V. J., "Brain Electrical Imaging the Dose-Response Effects of Cigarette Smoking (With 1 color plate)," 22 Neuropsychobiology (#4) 236 (1989).

123. Goodman, Sondra, Director, Household Hazardous Waste Project, HHWP's Guide to Hazardous Products Around the Home, 2d ed (Springfield, MO: Southwest Mo St Univ Press, 1989) ("Carbon monoxide starves the body and brain of oxygen. Carbon monoxide poisoning produces symptoms ranging from headache, dizziness, flushed skin, disorientation, troubled thinking [impaired ethical and moral controls, aka 'abulia'], abnormal reflexes [e.g., "self-defense"], shortness of breath, fainting, and convulsions, to coma and even death. Heart problems are also aggravated by the presence of carbon monoxide because the heart must pump harder. Children, persons with respiratory illness [disproportionately smokers] or anemia, and the aged may be particularly sensitive. Chronic exposure to low carbon monoxide levels impairs judgment ['abulia'] and increases the time required to make decisions [time disorientation]," p 99.) [This data refutes notions of smoker "choice." Note also our overview, especially noting pushers' fraud].

122. Conrin, James, 11 Clinical Electroencephalography (#4) 180-187 (Oct 1980) ("General EEG differences appeared between smokers and nonsmokers," p 181. "Green and Arduini (1954) . . . found that cortical desynchronization was accompanied by regular waves in the hippocampus, and cortical synchronization was accompanied by hippocampal desynchronization. . . . On the other hand, Longo, Guinta and deCarolus (1967) presented data that indicated multifocal seizure activity . . . rather than just hippocampal foci. In any cases, these studies demonstrated some basic effects of nicotine on cortical arousal," p 185. And, "smoking does cause obvious changes in EEG activity," p 186. Indeed, "smoking heavily over long periods produces permanent changes in EEG activity," p 181. Brain cell death is evident: "Low doses of nicotine activate the EEG tracing while high doses cause convulsive seizures followed by electrical silence," p 184.)

121. Schalling, D and D. Waller, Acta Physiol Scand, Supp 479 p 53 (1980) (Showing that "amount of smoking tends to be associated with the personality traits of . . . impulsiveness . . . . (sensation-seeking), and psychopathy (Schalling 1977) . . . . These personality traits are among the few for which biological correlates have been consistently found. Among these are indices of a low level of reticular-cortical arousal (Schalling 1978), e.g., a low frequency of spontaneous fluctuations in skin conductance, and some EEG characteristics," p 53.)

120. In early 1980, both the government and the American Psychiatric Association issued books listing smoking in separate classifications for its mental effect—meaning, as a "mental disorder," in the International Classification of Disease, 9th ed. (ICD-9), p 231, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. (DSM-III), pp 159-160 and 176-178. Tobacco causes brain damage, is called "Tobacco Organic Mental Disorder" (TOMD). The Manual includes smokers in the TOMD category if withdrawal symptoms occur within 24 hours (most smokers have symptoms in two hours). An extensive analysis of the latter is found in a Veterans Adminstration litigation case by a veteran seeking compensation for tobacco-caused injury. Note that tobacco mental disorder symptoms include odd sterotyped gestures, typical of other mental disorders as well. (The U.S. government, the IRS, deems treatment for this mental disorder, smoking, as a valid medical deduction, as valid as for a deduction for treating any other mental disorder; see the 1982 Michigan Law Review advocacy article).

119. Weeks, David J., "Do chronic cigarette smokers forget people's names?" 2 Brit Med J (#6205) 1627 (22-29 Dec 1979) ("There is evidence that cigarette smoking encourages the formation of generalised atherosclerosos. This could impair arterial blood supply to the brain and thus cause a fundctional deficiency that would show up on psychometric testing . . . An inferior memory for names connected to faces significantly differentiated smokers from non-smokers." "The non-smokers scored a mean (±SD) of 8.81 ±2.74, and the smokers a mean of 6.73 ±2.92. The difference is highly significant (P>0.005). Nonsmokers completed the matching on average about 10 seconds faster than the smokers . . . .")

118. Jaffe, Prof. Jerome H., M.D. (Columbia University), "Tobacco Use as a Mental Disorder: The Rediscovery of a Medical Problem," Research on Smoking Behavior: NIDA Research Monograph 17, pp 202-217 (Dec 1977) (citing rediscovery; this rediscovery of already known-data was needed due to the tobacco taboo cited by Dr. Lennox Johnston [1952], the deliberate long-term media policy of censoring and suppressing awareness of that data, and the perverse insistence that tobacco-induced mental disorders and brain damage are merely a 'habit.' It was thought in December 1977 that this censorship policy might be overcome, and that once the public knew smoking is a mental disorder, not a habit, that would have a major impact on the public's perception of smokers ("a profound effect upon the reputation of this behavior"!)

117. Friedman, J., T. Horvath, and R. Meares, 248 Nature 455-456 (29 March 1974) (Smoker delusional and uniqueness symptoms include "that the immediate effect of tobacco smoking" is "to greatly increase" unresponsiveness to stimuli) (For related material, in brain damage context, click here; in addiction context, click here; in "semantic illusion" context, click here.)

116. Burns, B. H., M.D., D.P.M., "Chronic Chest Disease, Personality, and Success in Stopping Cigarette Smoking," 23 Brit J of Prev and Soc Med (#1) 23-27, at 24 (Feb 1969) (smoker symptoms such as absurd delusional uniqueness beliefs: "persistent smokers . . . considered that their own chests had become immune to the effects of smoking"; some smokers said that smoking "was positively useful") (See

similar 1942 analysis; and brain-damage-data context for said delusions of grandeur of invincibility, and background on tobacco's

damaging the Self-Defense Reflex.)

115. Ulett, J.A., and T. M. Itil, "Quantitative Electroencephalogram in Smoking and Smoking Deprivation," 164 Science 969-970 (1969)

114. Brown, Barbara, "Some Characteristic EEG Differences Between Heavy Smoker and Non-Smoker Subjects," 6 Neuropsychologia (#4) 381-388 (Dec 1968)

| Nicotine is dangerous, "nicotine rapidly accumulates in brain tissue," p 385.

"The differences in both sustained EEG patterns and responsiveness indicate marked differences in central neuronal activity between habitual smokers and non-smokers," p 387.

There are "distinctive differences in brain wave patterns between heavy smokers and non-smokers. . . . All heavy smoker subjects evidenced an attitude of slight agitation or anxiety. . . . The differences in responses . . . found between the heavy smoker and non-smoker groups . . . are more likely related to fundamental differences . . . underlying brain electrical activity. Responses . . . were consistently fewer in the smoker group," p 385.

Also, "the amount of alpha activity present in the EEGs of heavy smokers was significantly less than that found for non-smokers. Also, the frequency of alpha was significantly faster in the heavy smoker group. Further, the quantity of high frequency rhythmic (and synchronous) activity was marked in the EEGs of heavy smokers and negligible in the EEGs of non-smokers," p 382.

Thus, "the fast EEG patterns of the heavy smoker is related to diffuse rather than focused attention," p 387. (Meaning, smokers' brain damage makes them more distractable).

Re responsiveness to stimuli, "peak times occurred earlier in the responses of the nonsmokers and the differences were statistically significant," worse, "the values for former smokers resembled those for the heavy smokers," p 384 (verifying that they don't recover from the brain damage). |

113. Armitage, A. K., G. H. Hall, & C. F. Morrison, 217 Nature 331-334 (27 Jan 1968) ("the pharmacology of nicotine has been studied in considerable detail since Langley [1889] first showed that nicotine stimulated then paralysed ganglion cells")

112. Murphree, Henry B. (Ed.), "The Effects of Nicotine and Smoking on the Central Nervous System," 142 Annals of the N Y Acad of Sciences 1-133 (1967)

111. Ginzel, K. H., "Introduction to the Effects of Nicotine on the Central Nervous System," 142 (#1) Annals N Y Academy of Sciences 101-120 (15 March 1967)

110. Brain, W. R., "Drug Addiction," 208 Nature 825-887 (1965) (tobacco as drug of dependence)

109. Knapp, Peter H., M.D., et al, “Addictive Aspects in Heavy Cigarette Smoking,” 119 Am J Psychiatry (#10) 966-972 (April 1963) (Smokers' typical brain-damage symptoms include "distorted time perception"; smokers "spoke about time moving slowly"; smokers showed "marked denial of concern . . . about any dangers associated with tobacco" showing impaired self-defense reflex ability to comprehend future consequences of current actions, e.g., current smoking's future effects)

Smokers' time disorientation was confirmed anew by Laura C. Klein, Ph.D., Elizabeth J. Corwin, Ph.D., and Michele M. Stine, M.Ed., "Smoking Abstinence Impairs Time Estimation Accuracy in Cigarette Smokers ," 37 Psychopharmacology Bulletin (#1) 90-95 (10 May 2003).

See also time continuuum data.

Re smokers' being in denial about the hazard, see, e.g.,

Richard M. Restak, M.D., The Mind (New York: Bantam Books, 1988), p 135

Lennox Johnston, "Tobacco Smoking and Nicotine," 243 The Lancet,

pp 741 and 742 (19 Dec 1942).

See also Amber Moore, "Future-Minded People More Likely to Ditch Smoking" (Medical Daily, 5 September 2012) ("

People who think about the future are more likely to quit smoking than those who don't, a new study says.")

|

108. W. Kalow, M.D., "Some Aspects of the Pharmacology of Nicotine," 4 Applied Therapeutics (#10) 930-932 (Oct 1962), supra (". . . there is a wealth of observations proving that nicotine has many actions on the central nervous system. In the brain as in the periphery, small doses of nicotine tend to stimulate functions which are blocked by higher doses. . . . Condition reflexes have been inhibited in . . . "Nicotine in fairly high doses causes desynchronization in the electro-encephalogram. In sufficiently large doses typical [epileptic] 'grand mal' seizure patterns appear. Tremor is a result of central stimulation by nicotine," p 932. "In toxic doses, nicotine blocks parasympathetic ganglia," p 931.) [See also B. Rush's 1806 findings, infra].

107. Silvette, Herbert, Ph.D., Paul S. Larson, Ph.D., H. B. Haag, M.D., "Actions of Nicotine on Central Nervous System Function," 14 Pharmacological Review (#1) 137-173 (March 1962) (history of tobacco effects on brain, as per "a grant from the Tobacco Industry Research Committee for literature research on the biologic effects of tobacco")

106. Barry, Maurice J., Jr., M.D., "Psychologic Aspects of Smoking," 35 Staff Meetings of Mayo Clinic (#13) 386 (22 June 1960) (cites at 387 smoker mental disorder symptoms including “rebellion” and “a considerable feeling of defiance for authority and the individuating thrill of setting aside some rule.” Also: "Clinical experimental data indicate that a definite physiologic addiction to nicotine exists," and "indicating pharmacologic addiction to nicotine.")

105. Dunlop, C. W., Stumpf, C., Maxwell, D. S. and Schindler, W., "Modification of cortical, reticular and hippocampal unit activity by nicotine in the rabbit," 198 Amer J Physiol 515-518 (1960) (identifying "action of nicotine on the EEG pattern as relatively specific, and as apparently due to alterations in hippocampal excitation")

104. Stumpf, C. "Die Wirkung von Nicotin auf die Hippocampustatigkeit des Kaninchens," 235 Arch exp Path Pharmak 421-436 (Germany, 1959) ("EEG discharge pattern, similar to that seen in convulsions, followed the intravenous administration of nicotine")

103. Hauser, Harris, B. E. Schwarz, Grace Roth, and R. G. Bickford (Mayo Clinic), "Electroencephalographic changes related to smoking," X The EEG Journal 576 (Aug 1958) ("Cigarettes contain several substances capable of producing profound Central Nervous System changes.")

102. Myers, Jack D., "Effects of Cigarette Smoking and Intravenous Nicotine on the Human Brain," 17 Fed Proc (#1) 672 (March 1958) ("Electroencephalograms . . . revealed an intermittent flattening lating 1-30 sec. . . . could be an abnormal attention response.") ("Supported by a grant from the Tobacco Industry Research Committee.")

101. Morocutti, C. and Sergio, C., "Azione di alcune sostanze simpaticomimetiche sull'attivita convulsiva da nicotina nel coniglio," 28 Riv Neurol 216-226 (Italy, 1958) (nicotine producing epileptic-type "cortical electrical activity [with] 'spikes'")

100. Silvestrini, B.: "Neuropharmacological study of the central effects of benactyzme and hydroxyzme (cerebral electrical activity, alarm and flight reaction on hypothalamic stimulation, central antagonisms)." 116 Arch int Pharmacodyn 71-85 (1958) ("nicotine fully reproduced the picture of an attack of 'grand mal,' the EEG tracing showing the convulsive pattern")

99. Sacra, P. and McColl, J. D., "Effect of ataractics on some convulsant and depressant agents in mice," 117 Arch int Pharmacodyn 1-8 (1958) ("nicotine produced its central convulsant action at the level of the diencephalon . . . upper levels of the central nervous system have been broadly implicated as sites of the convulsive action of nicotine")

98. Miley, Robert A., and W. G. White, "Giving Up Smoking," Brit Med J (#5062) 101 (11 Jan 1958) ("There is evidence that a large number of patients would like to give up smoking . . . but [alluding to the 'abulia' concept] lack the necessary will power. . . . ")

97. Spillane, John D., M.D., F.R.C.P., "The Effect of Nicotine on Spinocerebellar Ataxia," Brit Med J (#4952) 1345-1351 (3 Dec 1955) ("Ataxia resulting from disturbance of spinocereballar mechanisms is a characteristic feature of disseminated sclerosis and the spinocerebellar degenerations. The latter are a group of disorders characterized by progressive incoordination, of which the pathological basis is degeneration of the cerebellum and associated tracts in the brain stem and spinal cord," p 1345. "Tobacco-smoking had a striking effect on the dysarthria and on the ataxia of the lower limbs [in cited examples; in others] ataxia was noticeably increased," p 1351.) [Ed. Note: See also 1770's; 1882; 1911; 1915; and 1922 references.]

96. Yabuno, S., "Coma puncture by means of nicotinization," 32 Acta Sch med Univ Kioto 32-51 (1954) ("Histologic examination showed that the morphologic change in the [brain] area . . . with nicotine corresponded to that of destruction" and "gross convulsions following local applications of nicotine to various areas or regions of the CNS axis"; also, "corneal reflex and other reflexes to mechanical stimuli definitely sluggish")

95. Longo, V., G. P. Von Berger, and D. Bovet, "Action of nicotine and of the 'ganglioplegiques centraux' on the electrical activity of the brain," 111 Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (#3) 349-359 (July 1954) ("The administration of nicotine provokes a grand mal-like EEG discharge illustrating a central action of the drug," p 358. "The site of action is considered to be at the level of the reticular substance," p 359.)

94. Von Berger, G. P. and Longo, V. G., "Azione della nicotina sull'attivita elettrica cerebrale del coniglio 'encefalo isolato'," 29 Boll Soc ital Biol sper 431-435 (1953) (nicotine producing "a typical EEG picture of 'grand mal' convulsions")

93. Johnston, Lennox, "Cure of Tobacco-Smoking," 263 The Lancet 480-482 (6 Sep 1952) (citing cigarettes' mental effect, and the tobacco taboo).

92. Longo, V. G. and Bovet, D., "Studio elettroencefalografico dell antagonisme svolto dai farmaci antiparkinsoniani sui tremori provocati dalla nicotina." 28 Boll Soc ital Biol sper 612-615 (1952) (nicotine causing "a typical EEG picture of "grand mal" convulsions")

91. Archie W. Miller and P. S. Larson (Dept. of Pharmacology, Med. College of Virginia, Richmond), "Detoxication of nicotine by tissue slices," 11 Fed Proc 376 (March 1952) (findings, some body tissues (liver, kidney, etc., can detoxify nicotine, no instance of brain ability to do so was found; cited prior verifying studies by Werle et al., Biochem Ztschr 298: 268 (1938); 308: 355 (1941); 313:182 (1942); 318: 531 (1948))

90. Ottonello, P., "Recidivating Cerebral Angiospasms Due to Chronic Tobacco Intoxication," 18 Resenha clin. -cient 211-214 (June 1949)

89. Wood, Frank L., M.D. What You Should Know About Tobacco (Wichita, KS: The Wichita Publishing Co, 1944), p 110 (citing "the soothing or paralyzing effects of nicotine upon nerve endings. This action is probably two-fold as far as the brain is concerned, for in addition to its benumbing effects upon the nerve endings of sensation, there is probably an interference with the blood supply to the cortex of the brain which also reduces the perception of both pleasurable and unpleasant sensations. This is a true narcosis as far as the brain is concerned, for it helps to shut out unpleasant thoughts and sensations and thus, has a euphoric effect similar to that of alcohol and opium. . . ."

88. Kellogg, John H., M.D., LL.D., cited by Dr. Jesse M. Gehman, Smoke Over America (East Aurora, N.Y: The Roycrofters, 1943), p 216. ("Under the influence of tobacco, the judgment, the will, the conscience, the imagination even mental and moral faculty, are changed-all are nicotinized. . . . In other words, 'The pipe, cigar or cigarette dream' is a sort of temporary drug insanity." [In reality, permanent.] And: ". . . the immediate effect of smoking . . . is a lowering of the accuracy of finely coordinated reactions (including associative thought processes), p 88.)

87. Ozaki, K., "Thalamic epileptic convulsion," 5 Jap J Brain Physiol 79-88 (1942) ("gross convulsions following local applications of nicotine to various areas or regions of the CNS axis")

86. Sehlstedt, P., "Psychosis Due to Abuse of Tobacco," 34 Svenska läk. tidning 1574-1577 (12 Nov 1937)

85. Pappenheim, Eise, and Ervin Stengel, "Psychopathology of Smoking," 50 Wien klin Wehnschr (#9) 354-356 (5 March 1937)

84. Pappenheim, Eise, and Ervin Stengel, "Atypical Effects of Smoking Cerebral Disease," 105 Arch f Psychiat 623-645 (1936)

83. Rizzolo, A., "Clonus and generalized epileptiform convulsions caused by local applications of strophanthin, theine and nicotine on the cephalic end of the central nervous system," 50 Arch Farmacol sper 16-30 (1929) ("gross convulsions following local applications of nicotine to various areas or regions of the CNS axis")

82. Earp, J. R., "Tobacco and Scholarship," 26 Sci Monthly 119-126 (30 Jan 1928) (Cites allegation: "'The brain contains three kinds of cells: memory cells, intelligence cells and conscience cells' . . . All three kinds . . . are ruined by tobacco.")

"The term 'narcotic' is broadly defined to encompass any substance, including . . . hallucinogens, which directly induces sleep, allays sensibility, or blunts the senses, and which, when taken in large quantities, produces narcotism or insensibility."—25 Am Jur 2d, Drugs, Narcotics, and Poisons § 2." Annot., 92 ALR3d 47 (1979).

Narratives: Dr. Lévy; Dr. Depierris; Meta Lander; Dr. Nims; Thos. Edison;

Dr. Bewley; Dr. Tracy

"The 18th-century smoking club [used] the devilish herb. In this milieu, its [tobacco's] narcotic effects are plainly, blatantly sought and achieved," says "The Culture of Smoke: High-Life" (New York Public Library, 1997-1998, citing 18th century awareness of tobacco as narcotic, a fact now little known but then common-knowledge. |

81. Sollman, T. H., Manual of Pharmacology, 3rd ed (1926) ("Nicotine is one of the most fatal and rapid of poisons . . . . It acts with a swiftness equalled only by hydrocyanic acids." It is like "other narcotics," e.g., opium, cannabis, mescaline, and peyote.)

80. Binet, Leon, "La Fumée de Tabac: Est-Elle Un Poison du Cerveau?" 33 La Presse Médicale (#9) 134-135 (31 Janvier 1925).

| This 1925 article summarizes already extant data that tobacco smoke is a brain poison causing "éclatement." Here is the background.

At 135, "Ces faits sont suffisamment nombreux, suffisament précis pour affirmer une action nocive du tobac sur le cerveau." The facts are sufficiently manifold and exact to be able to affirm a harmful action of tobacco upon the brain.

Binet notes the problem that nicotine, once inside the person, is not eliminated except very slowly, "La nicotine que passe ainsi dans l'organisme ne s'élimine qu'avec une grande lenteur."

The smoke is also comprised of other chemicals, by-products of combustion, and especially, carbon monoxide, "De plus, la fumée de tabac ne contient pas seulment de la nicotine; on y trouve encore de la nicotianine, des bases pyridiques et des produits de combustion, et, en particular, de l'oxyde de carbone."

Prolonged tobacco use results in lesions in the cerebral cortex. "On note des lésions celluaires dans l'écorce cérébrale, après intoxication par la fumée de tabac. . . . le maximum de lésions . . . du système nerveux." Cells are lesser in number, and show deterioration. "Les lésions cellulaires se constatent sur les différentes circonvolutions et dans les différentes couches de l'écorce . . . les corps granuleux sont diminués de nombre, poussiéreux, décolorés . . . . un véritable éclatement de certaines cellules." An "éclatement" is translated "bursting, breaking up, explosion." (Definition by Ernest A. Baker, M.A., D.Lit., ed., Cassell's French-English Dictionary [London: Cassell & Co, Ltd, 1920], p 227). An example useage of the word "éclatement" refers to a tire "blowout."

For example, "La nicotine est capable de déterminer de la congestion cérébrale." Nicotine causes cerebral congestion. Binet cited E. Wertheimer, in Archives de Physiologie normale et pathologique, 1894, p 302, as noting that "L'augmentation de volume du cerveau . . . 'débute avec l'élévation de pression, bien que le coeur soit encore ralenti à ce moment; mais elle arrive à son maximum quande la paralysis du pneumogastrique a succédé a son excitation initiale.'"

Brain damage such as abnormally increased brain size involves a combination of factors, increased blood pressure, altered heart rate, etc., repeated fluctuations as smokers take doses of poison, then it wears off, they take more, etc. Binet states that "l'influence vaso-notrice vient se joindre une accélération considérable du coeur."

At 134, "La nicotine produit une augmentation considérable du volume du cerveau." Nicotine produces a considerable increase in brain volume (swelling). This is not a favorable effect. Compare with data from George W. Jacoby, 50 N Y Med J 172-174 (17 Aug 1889), infra, at 172, discussing carbon monoxide, a "gas . . . acting as a direct poison upon the brain and medulla oblongata. The walls of the vessels also lose their tonus, become dilated, and rupture easily. Autopsies have revealed large foci of softening in the brain, hæmorrhages into the meninges, and capillary apoplexies in the brain substance." "A few inhalations of the pure gas produce convulsions." Such data is consistent with swelling, "une augmentation considérable du volume du cerveau."

See also 71 Medical Record (#26) 1072-1073 (29 June 1907), on tobacco, "In chronic poisoning . . . Hyperemia of the lungs, brain, and [spinal] cord is found."

A brain "éclatement," expressing the concept of "bursting," or "explosion," like a tire "blowout," is clearly something to avoid. We can get new tires, but we cannot get a new brain! |

79. Hull, Clark, The Influence of Tobacco-smoking on Mental and Motor Efficiency (Princeton, 1924)

78. Brill, Abraham A., Ph.B., M.D. (1874-1948), 3 Internat'l J of Psychoanalysis (#4) 430-444 at 437-8 (Dec 1922) (has example of smoker's impaired impulse control: having the "sadistic life quite unimpeded," "liked blood," and the "powerless" aspects of the victim)

(See U.S. slavery examples:

axe murder,

burning,

torture,

whipping).

77. Kellogg, John H., M.D. (1852-1943), Tobaccoism, or, How Tobacco Kills (1922), p 77, "prolonged use of tobacco is recognized as one of the most common causes of insanity";

p 78 reports "tobacco ataxia";

p 78 also reports schizophrenia (100% correlation);

pp 81-82 report “neurasthenic symptoms,”

p 84 reports “difficulties in speaking and writing, defects of word memory, aphasia, neuralgia . . . ,”

and p 88 reports that "the accuracy of mental operations is definitely diminished by smoking . . . 'It is strongly indicated that the immediate effect of smoking . . . is a lowering of the accuracy of finely coordinated reactions (included associative thought processes'" [i.e., ability to comprehend causation vs. mere correlation]).

76. Tracy, James L., M.D., 23 Med Rev of Reviews (#12) pp 815-820 (Dec 1917) ("Tobacco intoxication is an egotistic narcosis. Tobacco makes the user feel like parading the narcosis and the manner and act of taking the narcotic. The narcosis is a [delusions of] grandeur narcosis. It is intrusive and obtrusive . . . most intolerant of restraint . . . ." In other words, part of smokers' mental disorder symptom pattern is that they are showing off by their littering. Other conditions, the afflicted may, e.g., vomit, spew all over. Smokers' disordered condition, they litter, spew all over. Worse, smokers assume that their behavior “which is so pleasant to the user is without question pleasant to every one else.” Thus: "So far, in fact, does this grandeur impression carry, that to the user of tobacco any opposition to its use at once suggests that there is mental abnormality in those who would interfere with its use.”) [Quoted; Examples:

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14. See also Lorillard document with context on tobacco industry evading reference to the littering issue. Note overview on smokers' unresponsiveness to normal stimuli, and time disorientation, including inability to comprehend their poisoning the environment, via their spewing quantities of tobacco chemicals, above safe limits, tobacco plumes, and tobacco particulates, and the need in self-defense to stamp out said psycho-behavior of theirs. Also note that when media articles occur on the subject, smokers are typically targeted, not the pushers who typically hooked them as youths. This manipulation of emphasis is due to the tobacco taboo in the media and to money-motivation by treatment types.]

This 1917 data is still timely. Re smokers' "parading the narcosis," for example, "along a 300-foot stretch [of freeway] one July day [were] dozens of cigarette butts," says "Trash Register," National Geographic, Vol. 214, Issue 6, December 2008, p 33. "Cigars and cigarettes leak toxic chemicals into watersheds." And, "anti-litter campaigns and ongoing cleanup [occur] at a cost of $11 billion a year."

When smokers throw used e-cigarettes onto the streets, they, like burning butts, cause problems beyond littering: lighted butts cause fires, and used e-cigarettes cause flats. Tony Dewildt, manager of Bay City's Belle Tire: “We have seen usually 1 or 2 a week puncturing the tire. . . . They’re all made out of metal, so when they slash a tire, they usually leave a pretty big gash in it,” typically leaving the tire unrepairable," says "E-cigarette cartridges puncturing tires" (WGAL News, Bay City, Michigan, 26 November 2013).

|

75. Scholl, B. Frank, Ph.G., M.D., ed., Library of Health: Complete Guide to Prevention and Cure of Disease (Philadelphia: Historical Publishing Co, 1916) ("It is to be doubted whether any sane adult ever deliberately learned the tobacco habit. . . . it is to be doubted whether a sane man exists who does not deprecate the habit

[craving] and wishes he were rid of it" [p 1486].)

74. Edison, Thomas, Letter (26 April 1914) (Tobacco "has a violent action on the nerve centers, producing degeneration of the cells of the brain. . . . this degeneration is permanent and uncontrollable [irreversible]")

73. Gy, Abel, L'Intoxication par le Tabac (Paris: Masson et Cie, 1913) (on "toxic effects of nicotine upon the nervous system," with examples due to tobacco acting as "un grand poison des facultés psychiques," e.g., impaired "association des idées . . . diminution du pouvoir d'attention . . . aboulie, à la résignation, à une sorte de fatalisme, de désintéressement . . . mélancolie . . . l'hystérie" [p 127]; "intoxication . . . tremblement" [p 116]; and "delirium tremens nicotinique . . . hallucinations visuelles [p 126])

| Example: Hallucinating Smoker Starts Fire in Hospital (Ann Arbor (MI) News, 21 October 2012). "An intoxicated patient smoking an imaginary cigarette in a bed in one room of the recently expanded ER. 'He was trying to light a non-existent cigarette. He thought he had one, he didn't have one, that caused the bedding to catch on fire . . . '" injuring himself and the nurse on duty. |

72. Tidswell, Herbert H., M.D., The Tobacco Habit: Its History and Pathology (London: J. & A. Churchill, 1912), p 49 (close connection), and p 185 ("Tobacco is known to be a brain poison")

71. Frankl-Hochwart, Lothar Ritter von, Die Nervösen Erkrankungen der Tabakraucher (Wien: A. Hölder, 1912) (narrative "on the nervous disturbances of smokers") 1862-1914

70. Pel, Pieter K.: "Un cas de psychose tabagique," XIX Ann. med. Chir. 171 (1911)

69. Frankl-Hochwart, Lothar von, "Les Maladies Nerveuses des Fumeurs," Deutsch. milit. Zeitschr. (#5) (1911) (See summary in French)

68. Frankl-Hochwart, Lothar, "Die Nervösen Erkrankungen der Tabak-raucher," XXXVII Deutsch. med. Wehnschr. 2273, 2321 (1911)

67. Gy, Abel, Le Tabagisme, Étude Expérimentale et Clinique (Paris: G. Steinheil, 1909)

66. Guillain and Abel Gy, "Les lésions des cellules nerveuses corticales dans l'intoxication tabagique expérimentale," Soc Biol (12 December 1908) (See summary by Dr. Gy).

65. Vladytchko, "Altérations anatomo-pathologiques du système nerveux central et périphérique dans l'intoxication par la fumée de tabac," Vratch gaz (10 août 1908) (See summary by Dr. Gy).

64. Davison, Alvin, The Human Body and Health (New York: American Book Co, 1908) (tobacco "prevents the brain cells from developing to their full extent and results in a slow and dull mind."

63. Clarke, Leon Pierce, M.D., Tobacco Effects on Nervous System, 71 Medical Record (#26) 1072-1073 (29 June 1907) (Tobacco "registers a permanent and definite impression in nervous structures when it is used for months or years." "Ecchymosis occurs in the pleura and peritoneum. Hyperemia of the lungs, brain, and cord is found. . . . Coarse lesions have been found in the brain and spinal cord.")

62. Guillain and Gy, Nicotinic Convulsions and Paralysis, LXII Comp rend Soc d biol 604 (1907) (nicotine causing epileptiform convulsions and transient paralysis))

61. Lesieur, Nicotinic Convulsions and Paralysis, LXII Comp rend Soc d biol 430 (1907) (nicotine causing epileptiform convulsions and transient paralysis))

60. Gouget, Tobacco Poisoning and Convulsions, XIV La Presse Medicale 533 (1906) (nicotine always caused convulsions, and no tolerance, in rabbits)

59. Adler and Hensel, Nicotine and Convulsions in Rabbits, XV J Med Resch 229 (1906) (nicotine always produced convulsions, no tolerance developed, always same intensity regardless of dosage)

58. Dr. Robert Brudenell Carter (1828-1918), "Alcohol and Tobacco," 250 Littell's Living Age 479-493 (1906) ("The steady and progressive increase of insanity among us is the most important fact of the present day in relation to public health, and is such as to render the prevalence of cancer or of tubercle absolutely trivial by comparison. It is a matter of routine to attribute a large portion of this increase to drink, but may there not be something to say also about tobacco?"

57. Dr. Albert F. Blaisdell, Our Bodies and How We Live (Boston: Ginn, 1904) ("The cells of the brain may become poisoned from tobacco. The ideas may lack clearness of outline. The will power may be weakened, and it may be an effort to do the routine duties of life. . . . The memory may also be impaired."

56. Xoporkoff, "De l'intoxication chronique par le tabac," Revue de psychiatrie, de neurol. et de path. expérim (#4) (1903) p 262 (summary by Dr. Gy; tobacco impairs the flow of ideas).

55. Hall, Winfred S., Ph.D., M.D., Elementary Anatomy, Physiology and Hygiene for Higher Grammar Grades (New York: American Book Co, 1900. ("Tobacco contains a sharp-tasting liquid called nicotine, which is a quick-acting and deadly poison. Because of this poison, the juice of the tobacco is never purposely swallowed; but in chewing, the saliva dissolves the nicotine, and a part of it is absorbed into the system; while in smoking, the nicotine in the smoke and vapor is absorbed 72by the saliva and the moist membranes of the mouth and nose, where it exerts all of its harmful effects . . .," pp 71-72. "What has been said in the preceding lessons about the influence of alcohol upon the will power, applies with equal truth to such narcotics as tobacco and opium," p 73. [Context.]

54. Dr. Galtié, "Chorèe nicotinique," Gaz. Hop. de Toulouse, 13 April 1899 ("delirium tremens nicotinique" and "hallucinations visuelles")

53. Woods, Matthew, M.D., 32 J Am Med Ass'n (#13), "Some of the Minor Immoralities of the Tobacco Habit," pp 683-687 (1 April 1899) (Smoking "causes insanity" "to repeat again familiar facts," it “stupefies the moral sense,” “makes man selfish, unmannerly, and sometimes worse,” and “callous to the requests of others”) (See excerpt.)

52. Ballet, Gilbert, and et Maurice Faure, "Attaques épileptiformes produites par l'intoxication aiguë tabagique," C. R. Soc. Biol (17 February 1899); and Méd. mod (15 February 1899) (# 15), p 97 (See summary by Dr. Gy).

51. Buccelli, "Psychose polynévritique par intoxication tabagique," Riv di patol nerv e ment (June 1898) (tobacco-induced psychosis, summary by Dr. Gy).

50. Moore, B. and Row, R., "A comparison of the physiological actions and chemical constitution of piperidine, coniine and nicotine," 22 J Physiol 273-295 (1898) (nicotine causes motor paralysis via paralysis of intramuscular parts of motor nerves, and CNS action)

49. Tolstoy, Leo, Count (1828-1910), Lasterhafte Genüsse aka Vicious Pleasures (London: Mathieson, 1896), pp 36-91 ("Alcohol and tobacco") ("The brain becomes numbed by the nicotine." Conscience thus expires, as impulse control is impaired, thus linking to crime. (See Excerpt), and his Why Do People Intoxicate Themselves? [1890]).

48. Mulhall, J. C., M.D., 62 New York Med Journal 686-688 (30 Nov 1895) (citing "evil effects of cigarette smoking," for example, "nicotine intoxication" evident after a mere "three cigarettes." "The great [worst] evil of tobacco is its constitutional [systemic] effect on the nervous system. The much lesser evil is . . . on the upper respiratory system." Effect: "Nervous diseases and insanity are rapidly increasing in the American people." This "nerve destroying nicotine . . . which the cigarette so materially assists in spreading" endangers children. Mulhall hoped that the media "will publish . . . such information.") (See media censorship website on media refusal to educate on this subject.)

47. Chereau, Sur Quelques Cas d'Aphasie Transitoire chez des Fumeurs (Th. Paris, 1894) ("l'amnésie et l'aphasie nicotiniques")

46. Legrain, "Étude sur les poisons de l'intelligence," Annales médico-psychol (1891), pp 30, 215, 377. (tobacco hyperexcitability and hallucinogenic effects, summary by Dr. Gy).

45. Dr. Kjellberg, Upsula, Sweden, Weekly Medical Review (St. Louis, Mo., 29 Aug 1891) (citing "Nicotinic Psychosis (tobacco mental disease) among marines, and workmen in factories at Upsula who used tobacco . . . manifesting itself by feebleness, inactivity, and despondent ideas. Hallucinations follow at an early period, accompanied by depressive ideas and, later, by exalted and maniacal ideas and actions.") (And see Dr. Gy's summary.)

44. Dr. Kjellberg, Upsula, Sweden, Wiener Medizinische Presse, Vienna, Austria (17 Aug 1890) (identifying Nicotinosis Mentalis symptoms, e.g., distressing emotions of indisposition and weakness, hallucinations, and delusions with suicidal intent) (See similar 1876 data and 1990 data; and tobacco hallucinogen data.)

43. Dr. Gilbert, "Hystérie tabagique," Bull. et Mém. Soc. méd. Hop. de Paris, 25 octobre 1889 [Summary by Dr. Gy]

42. Wight, John B., Tobacco: Its Use and Abuse (Columbia, SC: L. L. Pickett Pub Co, 1889), p 106 ("Tobacco is also a brain poison. It injures the brain and weakens the nerves. When much used it causes loss of memory. It makes many who use it peevish and dissatisfied when for any reason they are without it for a short time. Like the other narcotics, appetite for it grows stronger constantly, and the more the appetite is satisfied the worse is the tobacco-user's condition.")

41. Pierce, Ray V., M.D., The People's Common Sense Medical Adviser in Plain English; or, Medicine Simplified, 21st ed (Buffalo NY: World's Dispensary Printing Office and Bindery, 1889), pp 384-385. ("The use of tobacco is a pernicious habit in whatever form it is introduced into the system. Its active principle [ingredient], Nicotin, which is an energetic poison, exerts its specific effect on the nervous system . . . . the tone of the system is greatly impaired, and it responds more feebly to the influence of curative agents. Tobacco itself, when its use becomes habitual and excessive, gives rise to the most unpleasant and dangerous pathological conditions. Oppressive torpor, weakness or loss of intellect, softening of the brain, paralysis, nervous debility, dyspepsia, functional derangement of the heart, and diseases of the liver and kidneys are not uncommon consequences . . . . A sense of faintness, nausea, giddiness, dryness of the throat, tremblings, feelings of fear, disquietude [paranoia], and general nervous prostration must frequently warn persons addicted to this habit that they are sapping the very foundation of health. . . . The opium habit . . . is open to the same objections." (Notice that opium is so far less a problem as to warrant only a one sentence reference!)) [See context.]

40. Jacoby, George W., 50 New York Medical Journal 172-174 (17 Aug 1889) (carbon monoxide is a "gas . . . acting as a direct poison upon the brain and medulla oblongata. The walls of the vessels also lose their tonus, become dilated, and rupture easily. Autopsies have revealed large foci of softening in the brain, hæmorrhages into the meninges, and capillary apoplexies in the brain substance." "A few inhalations of the pure gas produce convulsions.")

39. Langley, J. N., and W. L. Dickinson, "On the local paralysis of peripheral ganglia, and on the connexion of different classes of nerve fibers with them," 46 Proc Roy Soc 423-431 (1889) ("the pharmacology of nicotine has been studied in considerable detail since Langley first showed that nicotine stimulated then paralysed ganglion cells," said Armitage, et al.)

38. Gilbert, "Hystérie tabagique." Bull. et Mém. Soc. méd. Hop. de Paris (25 October 1889) (hystérie)

37. Lyman, Dr. C. W. 48 New York Med Journal 262-265 (8 Sep 1888) ("Nicotine is one of the most powerful of the 'nerve poisons' known")

36. Rouillard, Amédée, Effects du Tabac Sur L'Intelligence (Paris, 1886)

35. Rouillard, Amédée, Les Amnésies au Point de Vue de l'ètiologie (Th. Paris, 1885) (tobacco's sedative effect, summary by Dr. Gy).

| In a medical classic, Emil Kraepelin, Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie (1883), cited brain pathology in mental disorders, cited symptom patterns, and developed systematic classification of the type now developed as the DSM-IV.

|

34. M. Jolly, French Academy of Science (1882) (the increase of insanity in France parallels increased tobacco use; "the immoderate use of tobacco produces an affection of the spinal marrow and a weakness of the brain which causes madness"—cited by Meta Lander, The Tobacco Problem (1882), p 124 with an example at p 121; and that "tobacco is a great [major] cause of that disease," as cited by Ariel A. Livermore, Anti-Tobacco (1882), p 20).

33. Wyman, Hal C., M.D., "Tobacco Poisoning—Interesting Cases," 3 Detroit Lancet (#6) 249-250 (December 1879) (case 1, ataxia from "tobacco poisoning [of] the coordinating tracts of the cerebellum and spinal cord" leading to "vertigo" with "a reeling, staggering gait," misdiagnosed by laymen as due to alcholism; case 2, "epileptic convulsions" with "chorea of the left face, neck and arm," "facial nerve, hypoglossal, spinal accessory and cervical plexus affected by tobacco poisoning")

32. Périgord, De la Fumée de Tabac (Th. Paris, 1879) (smoker memory loss, see summary by Dr. Gy)

31. Chase, B. W., M.A., Tobacco: Its Physical, Mental, Moral and Social Influences (New York: Wm. B. Mucklow Pub, 1878). (Examples: "a lassitude follows the intoxicating influence of Tobacco. . . . The [brain] has the power of consecutive thought, but the Tobacco-user loses this power, and his thoughts jump from one thing to another—they cannot be gathered and concentrated. . . . The man who uses Tobacco dethrones his judgment . . . so as to produce insanity [according to] a large number of the most eminent physicians," pp 59-62.)

30. Dépierris, Hippolyte A., Physiologie Sociale: Le Tabac (Paris: Dentu, 1876) (symptoms including becoming "dépossédés du sens humain . . . par une impulsion qu'on ne peut qualifier que de folie . . . désordre . . . comme les bêtes fauves . . . . dégradation narcotique les abaisse . . . rage . . . ils déchirent, ils mutilent sans nécessité, par instinct féroce," p 342; and, "Avant le . . . tabac, la folie était une maladie très rare dans l'humanité," p 346. Note also his pp 277-291 (tobacco-induced hallucinations); pp 306-325 (tobacco-induced impairment of the moral sense); pp 326-344 (tobacco-induced crime); and pp 345-372 (tobacco-induced insanity data).)

29. Dr. Kostral, in Ann. d'Hygiène (1871) (tobacco effects include "congestion of the brain," cited by Ariel A. Livermore, Anti-Tobacco (Meadville, Penn.: 29 January 1882), p 20.)

28. Rosenthal, "Sur un phénomène observé dans l'empoisonnement par la nicotine," 4 C. R. Soc. Biol. 91-92 (Paris, 1867) ("in animals poisoned with nicotine, convulsions are followed by paralysis, resembling that produced by curare")

27. Mussey, Reuben D., M.D., Health: Its Friends and Its Foes (Boston: Gould & Lincoln; New York: Sheldon & Co; Cincinnati: George S. Blanchard, 1862, reprinted 1863 and 1866) ("tobacco . . . benumbs the moral sense," p 131)

26. Taylor, J., L.S.A., 1 The Lancet (#1749), p. 250, 7 March 1857 (Smoking behavior includes “an alarming passion for fraudulently obtaining . . . money. This propensity to . . . vicious habits . . . I . . . ascribe . . . to tobacco”)

25. Booth, Samuel, L.S.A., 1 The Lancet (#I(1748), p. 229, 28 Feb. 1857 (“The action of smoking on the brain” includes “great irritability of temper.”)

24. M'Donald, Dr. William, 1 The Lancet (#1748) 231 (28 Feb 1857) ("no smoker can think steadily or continuously on any subject. . . . He cannot follow out a train of ideas.")

Ed. Note: Another term for this smoker brain damage symptom is "schizophasia" (or "word salad)," reflecting thought disorder such as: "Classic verbal disturbances that might occur with schizophrenia include associative looseness, neologisms, clang association, word salad, and echolalia." (See definitions (at bottom of the website), example: "Associative looseness means one thought isn't connected to the next." Note that ". . . the immediate effect of smoking . . . is a lowering of the accuracy of finely coordinated reactions (including associative thought processes)."—John H. Kellogg, M.D., LL.D., F.A.C.S., Tobaccoism, or, How Tobacco Kills (Battle Creek, MI: The Modern Medicine Publishing Co, 1922), p 88, meaning, this aspect of schizophrenia (schizophasia) is an "immediate effect of smoking.")

"It results from dysfunction of the language centers in the cerebral cortex and basal ganglia or of the white matter pathways that connect them," says "Aphasia: Function and Dysfunction of the Cerebral Lobes."

This is due to the fact that "tobacco . . . so excites [damage] the brain as to make it impossible to concentrate the mind on one subject . . . followed by failing memory, incontinuity of thought," says Dr. G. F. Butler, cited in the book by Bruce Fink, Professor of Botany, Miami University, Tobacco (Cincinnati: The Abingdon Press, 1915), p 25.

One way this typical smoker brain damage symptom is displayed is — they change the subject. Note this behavior of smokers. This symptom becomes evident when a subject they don't want to deal with is raised.

As Thomas Edison well said, smoker brain damage is irreversible.

Note standard psychiatric data, the “special [warped] laws of logic that the schizophrenic uses in support of his complexes or ideas, which to us seem delusional. . . . keep in mind that” what “seems absurd to us is expressed . . . by the patient . . . To him, his idea is rational, unquestionable, based on an absolute conviction of its truth. His unconscious motivation, a desire that cannot be controlled . . . obliges the patient to use unusual ways of thinking,” p. 65, Understanding and Helping the Schizophrenic (New York: Basic Books, 1979), by Dr. Silvano Arieti. At 46, “The patient does not attempt to demonstrate the validity of his ideas. He 'knows'; that is enough. His knowledge comes from an inner, unchallenged certitude that does not require demonstration. 'He knows.'”

At 24, “To date, it has not been demonstrated that the schizophrenic can be taught or coerced or convinced not to have these thoughts,” says Schizophrenia: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments (New York: Norton, 1979), by Kayla Bernheim, Ph.D., and Richard Lewine, Ph.D.

|

23. Pidduck, Dr. J., Lancet (Issue #1746) 177-178 (14 Feb 1857)

("If the evil ended with the individual who by the indulgence of a pernicious custom injures his own health and impairs his faculties of mind and body, he might be left to his enjoyments—his 'Fool's Paradise'—unmolested. This, however, is not the case. In no instance is the sin of the father more strikingly visited upon his children than the sin of tobacco-smoking. The enervation, the hypochondriasis, the hysteria, the insanity, the dwarfish deformities, the consumption, the suffering lives and early deaths of the children of inveterate smokers hear ample testimony to the feebleness and unsoundness of the constitution transmitted by this pernicious habit."

And: "A leading physician in one of our largest cities, in speaking of those who have indulged in the use of tobacco for years with seeming impunity, adds: 'But I have never known an habitual tobacco-user whose children, born after he had long used it, did not have [Ed. Note: birth defects, e.g.,] deranged nervous systems and sometimes evidently weak minds. Shattered nervous systems for generations to come may be the result of this indulgence.")

22. Solly, Dr. Samuel (1805-1871), 1 The Lancet (#1746) p 176 (14 Feb 1857) (Tobacco is known "as one of the causes of insanity" as smokers do "become deranged from smoking tobacco") (See excerpts from his writings)

21. Neil, Dr. J. B., 1 The Lancet (#1740) 23 (3 Jan 1857) ("Dr. Webster states that, in the post-mortem examinations of inveterate smokers, cretinism [brain damage] is always present.") (So Americans were tobacco-avoiders.)

20. Alcott, William A., M.D., The Physical and Moral Effects of Using Tobacco as Luxury (New York: Wm. Harned, 1853), p 23 ("The slave of tobacco is seldom found reclaimable . . . . I know full well the difficulty of reclaiming the drunkard. But the tobacco drunkard is still less hopeful. I have, indeed, in the course of the last quarter of a century, met with instances of entire emancipation, but they have been few and far between.")

19. Harris, Elisa, M.D., The Effects of Its Use as a Luxary [Non-Necessity] on the Physical and Moral Nature of Man (New York: Wm. Harned, 1853), p 21 ("Most emphatically does tobacco enslave [addict] its votaries [addicts]. . . . It is the uniform testimony of those who have attempted to emancipate themselves from their attachment and bondage to tobacco, that to break the chains to which they are bound, requires the strongest efforts of reason, conscience, and the will.")

18. Lévy, Dr. Michel, Traite d'Hygiene Publique et Privée (Paris: J. B. Baillière, 1850) (". . . one perceives the stupifying effects, and the intellectual and moral degradation which result from the combined abuse of beer and tobacco . . . . Excess of tobacco enervates the intelligence, blunts the attention, enfeebles the memory. Smoking induces a kind of cerebral-sloth which ends in inaptitude of spirit, and an irremediable torpor of the faculties. It is an obstacle to the activity of men, a bar to civilization . . . ") (Longer Excerpt)

17. Bernard, Claude, M.D., D.N.S., "27e Leçon" (1850) (Nicotine produces "des convulsions excessivement violentes . . . un état effrayant . . . comme furieux . . . agités de mouvements désordonnés . . . prise d'un tremblement musculaire et périr.") (See excerpts from his writings)

16. Harlow, Dr. J. M., "Passage of an Iron Rod Through The Head," 39 Boston Med and Surg J (#20) 389-393 (13 Dec 1848) (producing same permanent effects as tobacco tantamount to a "shot through the head," and see similar 15 August 2012 incident)

In a medical classic, Wilhelm Griesinger, Die Pathologie und Therapie der Psychischen Krankheiten: Pathology and Therapy of Psychic Disorders (Stuttgart: Krabbe, 1845), explained all mental disorders in brain pathology terms.

Brain damage is known to impair / destroy ability to choose ("abulia"). For example, note “Korsakoff’s psychosis." It "was first described by the Russian psychiatrist [Dr. Sergei] Korsakoff [M.D., 1854-1900] in 1887. The outstanding symptom is a memory defect (particularly with regard to recent events) which is concealed by falsification. An individual may be unable to recognize pictures, faces, rooms, and other objects as identical with those just seen, although they may appear to him as similar. Such persons increasingly tend to fill in gaps with reminiscences and fanciful tales that lead to unconnected and distorted associations. There individuals may appear to be delirious, hallucinated, and disoriented for time and place, but ordinarily their confusion and disordered conduct are closely related to their attempts to fill in memory gaps. The memory disturbance itself seems related to an inability to form new associations. . . . some personality deterioration usually remains in the form or memory impairment, blunting of intellectual capacity, and lowering of moral and ethical standards." Source: James Covington Coleman, Ph.D., Abnormal Psychology and Modern Life, 5th edition, (Scott, Foresman & Co., 1976), p 420.

|

15. Mussey, Reuben D., M.D. (1836) (tobacco causes "confusion or weakness of the mental faculties, peevishness and irritability of temper, instability of purpose, seasons of great depression of the spirits, long fits of unbroken melancholy and despondency, and in some cases, entire and permanent mental derangement," cited in The Use of Tobacco: Its Physical, Intellectual, and Moral Effects on The Human System, by William A. Alcott, M.D. (New York: Fowler and Wells, 1836, p 36); reprinted by Dr. Mussey, 1862, p 101.