For perspective in, e.g., Ebola context (the virus hyped in late 2014 when a couple deaths occurred in the U.S.), see, e.g, Rachel Rose Jackson, "Ebola may be in the headlines, but tobacco is another killer in Africa" (The Guardian, 16 October 2014) ("another killer pandemic of tremendous significance continues to sweep the African continent relatively unnoticed. Tobacco kills one out of two long term users, or one person every six seconds. At current rates, it is set to kill 1bn globally before 2100 – that’s more than 200,000 times the current number of Ebola deaths. Millions of those who die will be African."

For perspective on the total 20th century killing level, see the Twentieth Century Atlas, "Source List and Detailed Death Tolls for the Primary Megadeaths of the Twentieth Century."

| "Philip Morris International (PMI) proudly announced its 2nd quarter earnings Thursday morning [18 July 2013]. For most companies, a positive earnings report is a day to celebrate. For PMI, it should be a day of shame, because PMI is in the business of selling the only consumer product that, when used exactly as intended, kills.

Let's get some perspective on PMI's numbers for 2012: - PMI's Share of the Global Market = 16.3% - Total Number of Deaths from Tobacco in 2012 = 6 million - PMI's 2012 Death Toll = 978,000 (more than the population of Austin, TX) - PMI's Earnings per Death = $14,519.00," says Kimberley Intino, ASH Deputy Director of Development (22 July 2013). |

|

|

| "'Every regular cigarette smoker is injured. . . .

"Cigarette smoking kills some, makes others lung cripples, gives still others far more than their share of illness and loss of work days. "Cigarette smoking is not a gamble; all regular cigarette smokers studied at autopsy show the effects.'" Reference: The FTC Report 1968, cited by A. A. White (Law Prof, Univ of Houston), "Strict Liability of Cigarette Manufacturers and Assumption of Risk," 29 Louisiana Law Rev (#4) 589-625, at 607 n 85 (June 1969). Lung cancer at 100% in smokers is one such effect. |

| acetaldehyde (1.4+ mg) | arsenic (500+ ng) | benzo(a)pyrene (.1+ ng) |

| cadmium (1,300+ ng) | crotonaldehyde (.2+ µg) | chromium (1,000+ ng) |

| ethylcarbamate 310+ ng) | formaldehyde (1.6+ µg) | hydrazine (14+ ng) |

| lead (8+ µg) | nickel (2,000+ ng) | radioactive polonium (.2+ Pci) |

| Cigarette Chemical | Emission | |

| acetaldehyde | 3,200 ppm | 200.0 ppm |

| acrolein | 150 ppm | 0.5 ppm |

| ammonia | 300 ppm | 150.0 ppm |

| carbon monoxide | 42,000 ppm | 100.0 ppm |

| formaldehyde | 30 ppm | 5.0 ppm |

| hydrogen cyanide | 1,600 ppm | 10.0 ppm |

| hydrogen sulfide | 40 ppm | 20.0 ppm |

| methyl chloride | 1,200 ppm | 100.0 ppm |

| nitrogen dioxide | 250 ppm | 5.0 ppm |

| "The modern tendency is to hold corporations criminally responsible for their acts. A corporation may also be held liable for crimes based on the failure to act."—Ronald A. Anderson and Walter A. Kempf, Business Law - Principles and Cases (Cincinnati: Smith-Western Pub Co, 1967), p 53.

"Von Clausewitz said that war is the logical extension of diplomacy." "Verdoux feels that murder is the logical extension of business." "It's all business. One murder makes a villain. Millions, a hero. Numbers sanctify. . . ." Quotes from Charlie Chaplin, Review of Monsieur Verdoux [transl. "A Comedy of Murders"] (1947). See also Jeffrey Clements, J.D., "The Real History of 'Corporate Personhood': Meet the Man to Blame for Corporations Having More Rights Than You": "The real history of today's excessive corporate power starts with a tobacco lawyer appointed to the Supreme Court" (6 December 2011). |

If no cigarettes were manufactured commercially, few if any people would be willing and able to prepare the ground, plant, care for, and grow their own tobacco plants, research the process of refinement and additives, including coumarin, develop and insert those additives, harvest and cure the tobacco, package it, etc. Cigarettes are the end product of a vast and extended "universal malice" planned, intended, manufacturing process.

| Exec Order 1992-3 | Law Support Letter # 1 | Anti-Cigarette Smuggling Finding | Law Support Letter # 2 | Governor's Overview |

|

"If you are really and truly not going to sell to children, you are going to be out of business in 30 years."--Bennett LeBow, Tobacco CEO, quoted by Georgina Lovell, You Are the Target: Big Tobacco: Lies, Scams-Now the Truth (Vancouver, B.C: Chryan Communications, 2002).

See the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rule entitled "Regulations Restricting the Sale and Distribution of Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco to Protect Children and Adolescents." 61 Fed Reg 44,396 (28 Aug 1996) (resulting rule codified at 21 CFR § 801, et al.). The FDA found that "cigarette and smokeless tobacco use begins almost exclusively in childhood and adolescence." 61 Fed Reg 45239. Minors are particularly vulnerable to Madison Avenue's exhortations, plastered on racing cars and outfield fences, to be cool and smoke, be manly and chew, and the FDA found "compelling evidence that promotional campaigns can be extremely effective in attracting young people to tobacco products." Id. at 45247. The pushers engage in fraud, even denying that nicotine is addictive! Pushers premeditate to resist pro-health actions and laws, see, for example, this article, "Australia challenges Ukraine on tobacco" (3 September 2012). In the challenge, "a Philip Morris International subsidiary" is via the Ukraine challenging "Australia's plain cigarette packaging rules." |

2. Perception of the Hazard

Writings on Tobacco Dangers

Danger to Nations As a Whole

| Analyses go beyond the immediate personal level danger. See, e.g.,

James Parton (1868) Dr. John Lizars (1859), Rev. John Wight (1889), Dr. Charles Slocum (1909), Prof. Bruce Fink (1915), and a related medical history overview. Analyses extend beyond the personal level to cover national data, e.g., the pattern of the smoking link to national downfalls dating from the Spanish conquistadores' conquest of Mexico [1519]. See their national-impact examples: |

|

Reason: Ignorare legis est lata culpa; to be ignorant of the law is gross neglect — five Latin sayings to the same effect, it [no 'ignorance defense' allowed] is such a well established concept. |

| "pose . . . a danger to life itself , . . . a danger inherent in the normal use of the product, not one merely associated with its abuse or dependent on intervening fortuitous events." Banzhaf v Federal Communications Commission, 132 US App DC 14, 29; 405 F2d 1082, 1097; 78 P.U.R.3d 87; 1 Media L. Rep. 2037 (1968) cert den 396 US 842; 90 S Ct 50; 24 L Ed 2d 93 (1969). |

| "wholly noxious and deleterious to health. . . always harmful; never beneficial . . . inherently bad, and bad only . . . . There is no proof in the record as to the character of cigarettes, yet their character is so well and so generally known to be that stated above, that the courts are authorized to take judicial cognizance of the fact. No particular proof is required in regard to those facts which, by human observation and experience, have become well and generally known to be true." Austin v State, 101 Tenn 563, 566; 48 SW 305, 306; 70 Am St Rep 703 (1898) affirmed sub nom Austin v Tennessee, 179 US 343; 21 S Ct 132; 45 L Ed 224 (1900). |

| "Most smokers do not view themselves at increased risk of heart disease or cancer." John P. Ayanian, M.D., M.P.P., and Paul J. Cleary, Ph.D., "Perceived Risks of Heart Disease and Cancer Among Cigarette Smokers," 281 J Am Med Ass'n (11) 1019-1021 (17 March 1999). See also the 11 January 1999 Testimony of Dr. Whelan, and key quote: "smokers never, even today, have sufficient information to make a decision about smoking." |

“Quod ab initio non valet in tractu temporis non convalescet. That which is bad in its commencement improves not by lapse of time. Quod initio non valet, tractu temporis non valet. A thing void in the beginning does not become valid by lapse of time.”—Black's Law Dictionary (5th ed, 1979), pp 1126-1127.

| "absorbed through the pulmonary circulation and [is[] carried by the systemic circulation to every tissue and cell, causing mutations of cellular genetic structures, deviation of cellular characteristics from their optimal normal state, accelerated aging, and early death from a body-wide spectrum of diseases,"—Ravenholt, R. T., M.D., M.P.H., 307 N Engl J Med (#5) 312 (29 July 1982). |

| “unfair to require that one who deliberately goes perilously close to an area of proscribed conduct shall take the risk that he may cross the line.” Boyce Motor Lines, Inc v United States, 342 US 337, 340; 72 S Ct 329, 331; 96 L Ed 367 (1952). |

| "It is obvious that the law does not encourage tampering with such matters [poisons. Thus], we [the Supreme Court] are not disposed to resort to . . . subtilities to defeat a law [against poisoning people] which, if severe, is to the public benignant and humane in its severity." "Where an unlawful act is done, the law presumes it was done with an unlawful intent, and here the act . . . was unquestionably unlawful . . . . "It is unnecessary to decide how far even positive proof that a man was misinformed as to the degree of injury likely to arise from the use of any substance would avail him in defense . . . intention is, in law, deducible from the act itself." |

| "the legal inference that he did it with intention of producing such effect as would naturally result from its reception," Carmichael, 5 Mich 10, 17-20; 71 Am Dec 769, 762-776.

"The greater susceptibility of some persons over others, to be affected by it, renders it [poison] still more dangerous," p 19/775. The poison, a mind-altering drug, acts to "take away the power of resistance" [the self-defense reflex], p 20/775, thus causing "the most deplorable effect . . . the dethronement of reason from its governing power." |

| "[1] take away the power of resistance [by producing an unsound mental condition] . . .

"[2] make [the user] an easy prey to [the pusher and other harm] "[3] work upon [the] physical system [so] as to excite . . . passions beyond the control of reason, and, "[4] in effect . . . produce, if not insanity, the most deplorable effect of insanity, which is the dethronement of reason from its governing power," Carmichael, 5 Mich 20-21, supra. See also comparable decisions, Commonwealth of Massachusetts v Stratton, 114 Mass 303; 19 Am Rep 350 (November 1873), and State of North Carolina v Monroe, 121 NC 677; 28 SE 547; 61 Am St. 686; 43 LRA 861 (1897). |

| "violation of the regulations [here, the principles herein] is evidence of negligence to be considered with the other facts and circumstances," Dunn v Brimer, 537 SW2d 164, 165 (Ark, 1976).

"In Michigan, violation of a statute is negligence per se." Thaut v Finley, 50 Mich App 611; 213 NW2d 820, 821 (1973). |

"The requirements of foresight and vigilance imposed on responsible corporate agents are beyond question demanding, and perhaps onerous, but they are no more stringent than the public has a right to expect of those who voluntarily assume positions of authority in . . . enterprises whose services and products affect . . . health and well-being . . . " United States v Park, 421 US 658, 672; 95 S Ct 1903; 44 L Ed 2d 489 (1975).

"'The accused [executive or tobacco seller], if he does not will the violation, usually is in a position to prevent it . . . '" Park, 421 US 658; 95 S Ct 1903; 44 L Ed 2d 489, supra.

"defendant had, by reason of his position . . . responsibility and authority either to prevent in the first instance, or promptly to correct, the violation complained of, and . . . failed to do so. [Conviction upheld]." Park, 421 US 658; 95 S Ct 1903; 44 L Ed 2d 489, supra.

"'touch phases of the lives and health of the people which, in the circumstances of modern industrialism, are largely beyond self-protection.'" Park, 421 US 658, 671-678 and n 35; 95 S Ct 1903; 44 L Ed 2d 489, supra."A conscious, intentional, deliberate, voluntary decision [to ignore others' safety] properly is described as willful." F. X. Messina Construction Corp v OSHRC, 505 F2d 701, 702; 2 O.S.H. Cas.(BNA) 1325 (CA 1, 1974).

"Precisely what happened is what might have been expected as the result . . . and is the natural and probable consequence . . . Malice is presumed under such conditions." Nestlerode v United States, 74 US App DC 276, 279; 122 F2d 56, 59 (1941).

"'regardless of human life, although without any preconceived purpose to deprive any particular person of life." State v Massey, 20 Ala App 56, 58; 100 So 625, 627 (1924).

"If an act be committed with a premeditated design to effect death, it is murder in the first degree; but if it is merely imminently dangerous to others, evincing a depraved mind, regardless of human life and without premeditated design, it is murder in the second degree." Montgomery v State, 178 Wis 461; 190 NW 105, 107 (1922).

not just NOT do as here is being done (mass death above the holocaust level), but also requires them to obey the pertinent laws and aid the victims of their past and current violations, while ceasing and desisting to commit more. The duty of prevention and of aid, is ancient, e.g., as shown in a 1913 conviction based on failure to meet the duty: "The defendant was charged with the duty to see to it that . . . life was not endangered; and it is apparent he could have performed that duty . . . " [And] "To constitute murder, there must be means to relieve and wilfulness in withholding relief." Stehr v State, 92 Neb 755; 138 NW 676, 678 (1913).

"A tortfeasor has a duty to assist his victim. The initial injury creates a duty of aid and the breach of the duty is an independent tort. See Restatement (Second) of Torts, § 322, Comment c (1965)." Taylor v Meirick, 712 F2d 1112, 1117 (CA 7, 1983).

"All murder which shall be perpetrated by means of poison, or lying in wait, torture, or by another kind of wilful, deliberate and premeditated killing . . . shall be deemed murder of the first degree." People v Wiley, 18 Cal 3d 162, 165; 133 Cal Rptr 135, 138; 554 P 2d 881 (1976). (Perhaps quoting from 18 USC § 1111.

"An instruction asked by defendant was to the effect that if, on the account of the diseased condition of Solberg, a blow of less force caused his death than would have been required to take the life of a healthy man, the defendant cannot be held guilty unless he knew of the true condition of the health of the deceased. The instruction was properly refused, and the jury were informed, in substance, that the condition of Solberg's health would not excuse defendant. Surely it cannot be claimed that a homicide may be excused on the ground that the man-slayer was ignorant of the fact that his victim's feeble condition [that he by his long refusal to obey the pertinent laws, had helped cause] was not such as to enable him to resist the violence." State v Castello, 62 Iowa 408; 17 NW 605, 606-607 (1883).

"If it appear from the evidence that the death of deceased was accelerated by . . . the defendant, his guilt is not extenuated, because death might have come from natural causes as a result of disease with which the deceased was afflicted at the time . . . ." Barron v State, 29 Ala App 137; 193 So 190, 191 (1939).

"Death in this case was not casually caused by misadventure and thus, in the sense that the defendant's conduct was capable of causing death in and of itself, that conduct was inherently dangerous to life. . . . The requirement that the danger posed be apparent does not require that death be certain or even probably, in the sense that it is more likely than not. . . ."

1885

"The danger of death . . . is not completely outside the realm of common knowledge . . . Although the death may have been an occurrence unexpected by the [specific] defendant, that [ignorance defense] fact alone cannot diminish the danger in which the defendant by his conduct chose to place . . . life. On the basis of all the evidence it was reasonable for the jury to be convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant's conduct was imminently dangerous to another.""An important consideration here is . . . This court has found the relative physical characteristics of the victim and assailant to be factors which may be considered in determining whether conduct is imminently dangerous. Wangerin v State . . . 73 Wis 2d [427] at 435; 243 NW2d [448] at 452; Kasieta v State, 62 Wis 2d 564, 570-571; 215 NW2d 412, 415-416 (1974). It is not unreasonable to infer that the physical trauma . . . will be greater . . . more frightening . . . the probability . . . greater than in the general case." Turner v State, 76 Wis 2d 1; 250 NW2d 713, supra.

"Precisely what happened is what might have been expected . . . and is the natural and probable consequence . . . Malice is presumed." Nestlerode v U.S., 74 US App DC 276, 279; 122 F2d 56, 59, supra.

"heart attack . . . failure of circulation . . . asphyxiation, the condition where the body tissues have an insufficient amount of oxygen and excess carbon dioxide." Turner, 76 Wis 2d 1; 250 NW 2d, 172, supra.

"manslaughter where death was caused by fright, fear, or nervous shock, and where the prisoner made no assault or demonstration against the deceased, and neither offered nor threatened any physical force or violence toward the person of the deceased." Ex parte Heigho, 18 Idaho 566; 110 P 1029, 1031-1032 (1910).

"If his [activity] violence so excited the terror of the deceased that she died from the fright, and she would not have died except for the assault, then the prisoner's act was in law the cause of her death." Ex parte Heigho, 18 Idaho 566; 110 P 1029, 1031-1032, supra.

"The law clearly covers and includes any and all means and mediums by or through which a death is caused by one engaged in an unlawful act." Heigho, supra.

"You are instructed that the defendant takes the plaintiff as [he / she] finds [him / her]. If you find that the plaintiff was unusually susceptible to injury, that fact will not relieve the defendant from liability for any and all damages resulting to plaintiff as a proximate result of defendant's negligence" (January 1982).SJI 2d 50.10 cites Daley v LaCroix, 384 Mich 4, 13; 179 NW2d 390, 395 (1970) and Richman v City of Berkley, 84 Mich App 258; 269 NW2d 555 (1978), as pertinent precedents.

"defendant cannot escape responsibility . . . under the doctrine of apportionment of wrongs, which the law does not do; the law does not apportion the wrong." Barron, 20 Ala App 137; 193 So 190, 191, supra.

"It is certain that [the victim] was greatly excited by the encounter. Immediately after it occurred he applied at a house in the vicinity for shelter, stating that he was afraid . . . on account of defendant . . . . A witness says of his appearance at that time: 'He acted just scared to death' . . . His health failed rapidly from that time." State v O'Brien, 81 Iowa 88;46 NW 752, 753 (1890).

"not disposed to resort to metaphysical subtilities to defeat a law which, if severe, is to the public benignant and humane in its severity." Carmichael, 5 Mich 10, 20; 71 Am Dec 769, 776, supra."Whenever . . . there is a positive physical effect produced, and the poison administered operates to derange the healthy organization of the system temporarily or permanently, we think there is an injury which, whenever it is reasonably appreciable, may be regarded as within the statute." Carmichael, 5 Mich 10, 20; 71 Am Dec 769, 776, supra.

- Cigarettes: What the Warning Label Doesn't Tell You: The First Comprehensive Guide to the Health Consequences of Smoking (Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 1997), and

- A Smoking Gun—How the Tobacco Industry Gets Away With Murder (Philadelphia: George F. Stickley, People's Health Library, 1984).

"It was the province of the jury to determine whether the wrong of defendant caused or contributed to his [the victim's] death. The fact that he was afflicted with a disease which might have proved fatal would not justify the wrongful acts of defendant, nor constitute a defense in law. State v Smith, 73 Iowa, 35; 34 NW 597. Nor would ignorance on the part of defendant of the diseased physical condition of Stocum excuse his acts. State v Castello, 62 Iowa, 408; 17 NW 605." State v O'Brien, 81 Iowa 88; 46 NW 752, 753, supra."If one counsel another to commit suicide, and the other, by reason of the advice, kill himself, the adviser is guilty of murder, as principal." Commonwealth v Bowen, 13 Mass 356 (Sep 1816). Tobacco pushers regularly, routinely, daily "counsel" their targets to buy, to smoke!

As was said by Justice Denman in the Towers Case, it would be 'laying down a dangerous precedent for the future' for us [judges] to hold as a conclusion of law that manslaughter could not be committed by [mere] fright, terror, or nervous shock [much less, toxic chemicals!! or counseling ingesting same]." Ex parte Heigho, 18 Idaho 566; 110 P 1031-1032, supra.

| “For nothing! I was condemned for nothing!”

“But what was the charge?” “The so-called charge was murder. . . .” “So you didn't murder anyone then?” “Murder! Never. They were killed, but not murdered.” — Eugene O. Smith, "The So-called Charge Was Murder," American Heritage, pp 64-74 at 73 (June/July 2005). |

| Chemicals in Cigarettes | Definitions (Legal) | Crime Prevention | Genocide Aspects | Government Corruption |

| Media Censorship | Medical Statistics | Michigan Law | Prosecuting Non-Enforcers | Human Rights Law Context |

| "The proof of the pattern or practice [of willingness to commit acts such as the above] supports an inference that any particular decision, during the period in which the policy was in force, was made in pursuit of that policy." Teamsters v U.S., 431 US 324, 362; 97 S Ct 1843, 1868; 52 L Ed 2d 396, 431 (1977).

Violations of criminal law can indeed result in damage to private citizens. Ware-Kramer Tobacco Co v American Tobacco Co, 180 F 160 (ED NC, 1910). Litigants can show as part of the evidence in his/her own case, the guilt of others linked to the current defendant, in showing a pattern. Locker v American Tobacco Co, 194 F 232 (1912). |

| The author's letter, "Make cigarettes illegal," Detroit Free Press, 13 Feb 2002, advocates criminal prosecution as per the data herein cited. |

| Discussion Group: More Participants Welcome |

For TCPG Home Page |

“Pardon one offense, and you encourage the commission of many.”—Publilius Syrus (~100 BC).

“Thou shalt not be a victim.

Thou shalt not be a perpetrator.

Above all, thou shalt not be a bystander.”

—Holocaust Museum, Washington, DC.

| In Germany they came first for the Communists, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a Communist. Then they came for the Jews, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a Jew. Then they came for the trade-unionists, and I didn't speak up because I wasn't a trade-unionist. Then they came for the Catholics, and I didn't speak up because I was a Protestant. Then they came for me and by that time no one was left to speak up. -- attributed to Rev. Martin Niemoller.

Please speak up for tobacco pushers' targets. When they seek enforcement of the anti-poisoning and anti-murder rules of law herein cited, they are often attacked with the knowingly and murderously false accusation that enforcement of these ancient laws makes for a modern "nanny state"!!) |

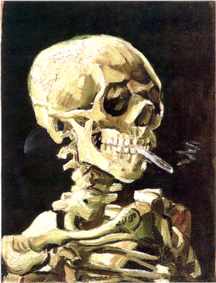

Graphic Credit

Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette

Vincent van Gogh, 1885-1886

The Crime Prevention Group

Copyright © 1987, 1999, 2006, 2007 TCPG