What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page revised in August 2015. |

Byzantine heritage between 1204 and 1453 Byzantine heritage between 1204 and 1453

You may wish to see an introductory page to this section first. During the XIIth century the emperors of the Comnenus dynasty revived the strength of the Byzantine Empire. After the death of Manuel I in 1180, a series of dynastic quarrels weakened it and led to its temporary end in 1204, when the Crusaders captured Constantinople and established what later on historians called the Latin Empire. This empire was partitioned between the leaders of the crusade and Venice which was rewarded with three eighths of its territory. As a matter of fact some Byzantine families retained control of key towns and provinces such as Trebizond and Nicaea. Venice was not interested in acquiring large land properties and chose to be given islands such as Candia and Negroponte which allowed control of maritime routes; Marco Sanudo, a Venetian adventurer, founded a duchy at Nasso. Constantinople retains very little evidence of the short-lived Latin Empire (1204-61). We know that a bell tower was built next to Hagia Sophia and a cycle of frescoes portraying the life of St. Francis was painted at Kalenderhane Camii.

The Genoese reacted to the growing influence of Venice over Constantinople, by strengthening their trading post at Galata on the northern shore of the Golden Horn. The only Gothic church of today's Constantinople can be found here. It was part of a Dominican monastery built in 1323-37 and it was also known as St. Paul's owing to a chapel dedicated to that saint. A tall belfry stood next to the church and gave the complex a very western appearance.

In 1261 the territory of the Latin Empire was reduced to just Constantinople, a small part of Thrace and a few fiefdoms in Greece. A small army sent by Michael VIII Palaeologos, the Byzantine ruler of Nicaea, profited from a temporary absence of the troops of Baldwin II, the Latin Emperor, and easily managed to enter Constantinople with the help of its Greek population.

The enemy of my enemy is my friend this saying was adopted as a key policy by the new rulers of Constantinople: in order to contain the growing pressure of the Ottomans on their eastern border, they sought an alliance with the Mongol Ilkhanate of Persia, which controlled also parts of Syria and Eastern Anatolia. In 1265 Emperor Michael VIII betrothed Maria, one of his daughters, to Abaqa Khan. She lived at the Mongol court for fifteen years until the death of her husband. Upon her return to Constantinople she was asked by her father to marry yet another Mongol khan; she preferred to become a nun and retired to a monastery which she renovated; its church was not turned into a mosque by the Ottomans, but the current building bears little resemblance to the original Byzantine church. Its interest lies in its historical background.

The Palaeologos dynasty ruled over a much diminished empire, especially after the loss of Bursa (1326) and Nicaea (1331) to the Ottomans. Without an army and a fleet Palaeologos emperors relied only on the walls of Constantinople to keep at bay Bulgarians and Ottomans, Venetians and Genoese. The best known monument of this period is St. Saviour in Chora, but probably at that time the complex of Theotokos Pammakaristos was regarded as a greater artistic achievement.

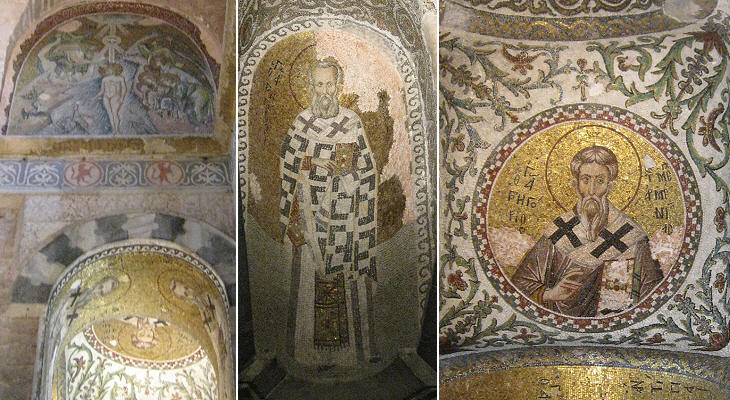

Theotokos Pammakaristos is a reference to the Joyous Mother of God; the church was built before the Latin conquest of Constantinople, but the Parecclesion, a funerary chapel decorated with mosaics and paintings, was added in 1310; this was dedicated to Christos ho Logos (Christ the Word) and a dedicatory inscription runs along its exterior walls. The complex remained a Christian building for more than a century after the 1453 Ottoman conquest of Constantinople: it was converted into a mosque only in 1591 by Sultan Murad III who called it Fethiye Camii (Mosque of the Victory) to celebrate his campaigns in the Caucasus. Until then it served as the church of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch.

The subject of the decoration is consistent with the Parecclesion dedication to Christ. We know that there were mosaics depicting episodes of his life in addition to portraits in the dome and in the apse: of these only one survived: the Baptism of Christ which can be seen in the picture below.

While the main building is still used as a mosque, the Parecclesion is now a museum (apparently with very few visitors, despite being located only a short distance from St. Saviour in Chora).

Euphemia was a young Christian girl of Chalcedon (a town opposite Constantinople on the Asian shore) who was martyred at the time of Emperor Diocletian. She was buried in a chapel in her hometown, but in the VIIth century, when Chalcedon was threatened by the Persians, her relics were moved to Constantinople to a church built inside a Vth century palace. According to tradition her sarcophagus was thrown into the sea during the Iconoclastic period, but it was eventually recovered and brought back to her church at the end of that period. At Rovigno in Istria however they claim that the sarcophagus washed ashore there. In the late XIIIth century the church of St. Euphemia was embellished with frescoes and reliefs. It was abandoned after the Ottoman conquest and the saint's relics were moved to the Orthodox Patriarchate.

Fanar, the Greek quarter of Constantinople after the Ottoman conquest, is currently the residence of the most religious Muslims of Istanbul; they came from rural regions of central and eastern Anatolia and settled in Fanar in the 1950s when a substantial number of Greeks left the city. They now pray with fervour in mosques which used to be churches. Vefa Kilise Camii shows its origin in the name because kilise means church. It was a church dedicated to St. Theodore and it was built making use of material from an earlier building; the tall fluted minaret recalls that of Antalya.

In some instances churches were largely modified when turned into mosques; changes were made to orient them towards Mecca. This is the case of a church which was known as St. Andrew in Krisei; parts of the original building can be detected in the interior but overall it has now a typical Ottoman design. Koca Mustafa Pacha was Master of Ceremonies and Grand Vizier of Sultan Beyazit II. He lost his position and his life in 1512 during a short, but very cruel fight among Beyazit's sons, who competed for succession.

Ayasma means holy spring and it is not uncommon to find Greek Orthodox churches or other religious establishments near a spring thought to have healing powers. The imperial palace of Blachernae was plundered and almost entirely destroyed after the conquest of Constantinople, but its famous holy spring continues to attract many people and not just Christians. It is not the only holy spring in the city: in addition to that of St. Karalamboy near the Golden Horn, there is another holy spring outside Silivri Kapi. A difficult coexistence

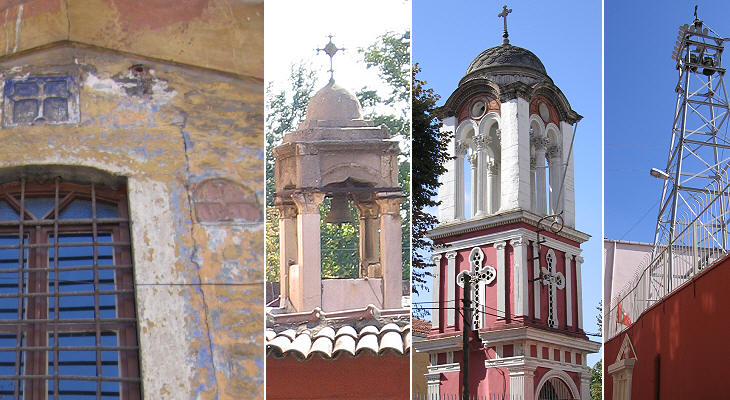

By wandering through the streets of Constantinople, especially in the neighbourhoods near the city walls, it is easy to come across the tips of small churches. They are hidden behind high walls after some of them were vandalised in 1955. For many centuries after the Ottoman conquest, a large Greek community continued to live in the city, especially in the neighbourhoods along the city walls. Tekfur Sarayi is a former Byzantine palace near Egri Kapi.

In the last years of their Empire, the Byzantine emperors sought the help of the western nations. In order to reach their objective they were prepared to accept the supremacy of the Pope. This policy was met with hostility by the Greek Orthodox clergy and by many influential families: according to tradition Loukas Notaras, a close advisor to Constantine XI, the last emperor, said: "I would rather see a Muslim turban in the midst of the City than the Latin mitre". Sultan Mehmet II, who conquered Constantinople in 1453, understood he could gain, if not the loyalty, at least the obedience of his new subjects by recognizing the role of the Patriarch of Constantinople. During the Ottoman rule the Patriarch was regarded as an officer of the State who directly reported to the Sultan; he was the head of an autonomous judiciary system which dealt with infringement of laws involving members of the Greek community.

The Armenian and the Jewish communities were given similar rights of self-government (millet system). Usually they were assigned sections of the town where they could live as happened at Jerusalem. In 1461 Sultan Mehmet II acknowledged the Armenian Patriarchate and assigned to its community the Samatya neighbourhood, the section of the Seventh Hill nearest to the walls. The Armenian Patriarchate was moved in 1641, but Surp Kevork is still an Armenian church and it houses other institutions of the community,

Many wives and mothers of the sultans were of Greek or Armenian descent and some of them protected their former co-religionists in a discreet way. Over time other Christian communities joined the Armenians at Samatya.

By and large almost all the churches on the Seventh Hill were redesigned in the XIXth century in various "modern" styles which had little to do with tradition.

Due to the frequent wars with Venice and to the decadence of Genoa, Greek merchants found great opportunities for taking control of trade in the Ottoman Empire. The Phanariots, the inhabitants of Fanar, acquired great wealth and economic power. Some of them were so trusted by the Sultans that they were appointed voivoda (prince/governor) of the Ottoman principalities in Romania.

In 1720 Sultan Ahmet III allowed the Greeks to rebuild in a larger size the church which was the seat of the Orthodox Patriarchate since ca. 1600. It is possible that the decision was influenced by the indirect help given to the Ottoman army during the 1714 re-conquest of Morea: the local Greek Orthodox population resented the Venetian attempts to promote Catholicism there and did not hinder the Ottoman return. The situation changed during the XVIIIth century when the Russian Empire became a great power. Empress Catherine II annexed the Crimean peninsula and made no mystery of her objective to conquer Constantinople; she sent a small fleet to the Aegean Sea to promote an insurrection of the Greeks. In 1821 the Greeks of Kalamata and Patras started a general rebellion which eventually led to the creation of a small Kingdom of Greece. In retaliation Sultan Mahmud II hanged Gregory V, the Patriarch of Constantinople, on the main gate of the Patriarchate.

During the second half of the XIXth century the Sultans made an attempt to regain the loyalty of their non-Muslim subjects by giving them new rights and by removing the limits on the size of their churches and institutions. The Phanariots took advantage of this opportunity and built a large and very visible school near Sultan Selim Camii.

The Armenian community built a large church in neo-Renaissance style at Uskudar, on the Asian side of the Bosporus. Similar to the Phanariots, the Armenians of Constantinople hoped to restore the ancient kingdom their ancestors had established in their homeland.

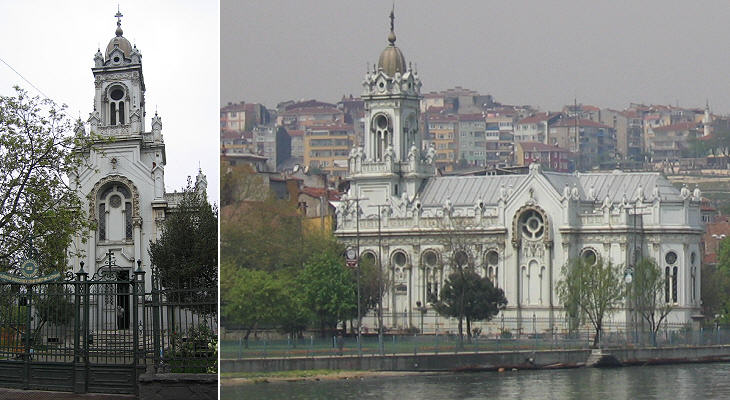

Whereas the Greeks were looking at freeing themselves from the Ottoman rule, the Bulgarians wanted to free themselves from the Greek (religious) control. The Patriarch of Constantinople was the head of the "Millet of Rum" the community which included all the Orthodox of the Ottoman Empire. The awakening of the Bulgarian nation started by asking the Sultan to establish a "millet" for them. This actually occurred in 1870, although Sultan Abdulaziz left in place supervision over some canonical matters to the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Bulgarians built a cast iron church on the Golden Horn: it was designed in a combination of different styles by an Armenian architect and it was made in Vienna and then shipped to Constantinople, where it was inaugurated in 1898.

The last years of the Ottoman Empire saw its economy fall into the hands of foreign companies; a new modern district was developed at Pera, behind Galata. French became the language spoken by the upper class and many French inscriptions can still be seen. WWI led to the collapse of the Ottoman Empire; the Greek Kingdom tried to annex Smyrna and western Anatolia. The failure of this attempt had dramatic effects on the Greeks of Constantinople and caused a split in the religious community with the creation of a small Orthodox Church loyal to the Turkish Republic. Another period of crisis for the Greeks of Constantinople occurred in the 1950s when Greece and Turkey were at loggerheads because of Cyprus. The last twenty years have seen an improvement in relations between the two countries and many Greeks visit Constantinople every year. Maybe one day the walls which protect the churches will not be needed any longer. Introduction to this section Roman Memories Hagia Sophia Hagia Irene and Little Hagia Sophia Roman/Byzantine exhibits at the Archaeological Museum Great Palace Mosaic Museum Byzantine Heritage - Other Churches (before 1204) St. Saviour in Chora First Ottoman Buildings The Golden Century: I - from Sultan Selim to Sinan's Early Works The Golden Century: II - The Age of Suleyman The Golden Century: III - Suleymaniye Kulliye The Golden Century: IV - Sinan's Last Works The Heirs of Sinan Towards the Tulip Era Baroque Istanbul The End of the Ottoman Empire Topkapi Sarayi Museums near Topkapi Sarayi The Princes' Islands Map of Istanbul Other sections dealing with Constantinople/Istanbul: The Walls of Nova Roma Galata Clickable Map of Turkey showing all the locations covered in this website (opens in another window). |