George M. Cohan In America's Theater | home

Stageography | What's New | George Washington, Jr. | The Merry Malones | Broadway Jones | 45 Minutes From Broadway | About Me | The Little Millionaire | Little Nellie Kelly | The Tavern | Seven Keys To Baldpate | Ah, Wilderness! | Get Rich Quick Wallingford | The Royal Vagabond | Discography & Filmography | Early years: 1878-1900 | Broadway Rise: 1900-1909 | Broadway Emperor: 1910-1919 | Decline & Fall: 1920-1929 | Little Johnny Jones | I'd Rather Be Right | Broadway Legend: 1930-1978 | Mailbag/Contact Me | Related Links | Articles & Thoughts | The Yankee Prince

Broadway Emperor: 1910-1919

At the beginning of this decade Cohan and Harris continued their overwhelming

success in the American Theater. While their successes from 1909 carried into

the following year, September saw their longest running show ever - "Get Rich

Quick Wallingford." It was also the year that Cohan & Harris became prominent

members in three organizations: The Lambs Club, The Players Club, and The

Friars. All three of these organizations were expressly formed to provide members

of the theatrical profession a place of recreation and relaxation. George M.

himself explained the difference between the clubs.

"The Players, is a group of gentlemen trying to be actors, The Lambs is a bunch

of actors trying to be gentlemen, and the Friars is a bunch of guys trying to be

both."

In particular, George enjoyed belonging to the Friars because it was the only

actor's club that his father Jerry belonged to. On April 3, 1910, The Friars

held a special banquet in honor of George M. Cohan. Jerry, needless to say,

was extremely pleased.

Cover of a Friars Program from 1916

George M. would go on to be named Abbot of the Friars more than any other

actor in the history of the organization. He served from 1912 -1919, 1921 - 1926,

and 1928 - 1932.

George and Agnes also had reason to celebrate that year. They became the

proud parents of a daughter, appropriately named Mary, and on September 13,

a second daughter, Helen (named after George's mother) was born. Almost

20 years later, Helen would appear along with her father in her Broadway debut

"Frendship" (1931).

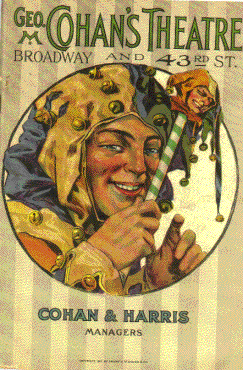

Program Cover for The Cohan Theater

On February 13, 1911 the George M. Cohan Theater opened its doors at 1482

Broadway & 43rd Street. It's narrow entrance lead to a marbled lobby which

had murals depicting the Four Cohans up until the event of "The Governor's Son."

After you entered the theater, you were treated to various scenes from his

Broadway successes that were painted on the walls above and surrounding

the boxes. The theater was virtually a shrine to his career. Opening night

featured "Get Rich Quick Wallingford," recently transferred from The Gaiety.

The theater, became a full time movie house in 1932, and by 1938 it was

demolished.

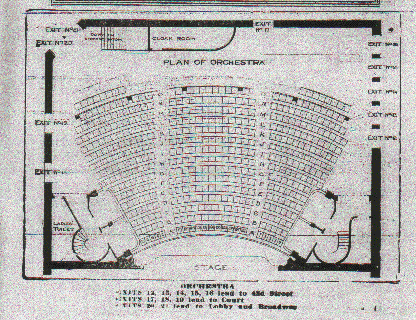

Lower level floorplan of the George M. Cohan Theater

Also, in 1911 George M. signed a contract with RCA Victor and on May 4,

made seven different recordings (click here to view) of his compositions. The

recordings don't really give justice to Cohan as either a singer or performer (he

had more energy and bounce in the dismal "Phantom President" 21 years later).

I suppose that it should be remembered RCA and other recording companies,

had primitive and/or no recording techniques in 1911 (i.e. a performer had to

compromise their performance in order to record a steady voice level). Even an

enigmatic performer like Al Jolson (who recorded "That Haunting Melody" in

1911) hardly can be judged by those recordings. But, they still remain our only

glimpse into what was. Incidentally, Jolson also performed "That Haunting

Melody" in his second show with the Shuberts, "Vera Violetta" (1911). It was

the popularity of the song caused Jolson to record it. Whatever the case, Cohan

must not have enjoyed the recording work, because he never went into the studio

to record again.

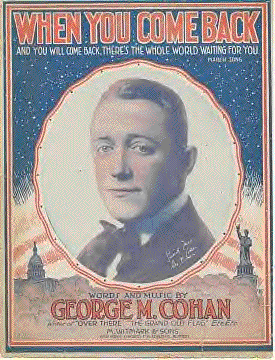

Sheet Music Cover of a song covered by

Al Jolson

In September of 1911 brought about more critical and financial success as George

starred with his father and mother in "The Little Millionaire." During the run of the

performance a young songwriter met his hero for the first time; Irving Berlin.

They formed a quick friendship, and when Cohan found out that Irving was the

author of "Alexander's Ragtime Band," he invited Berlin to write a few songs (which

Cohan interpolated in the final run of "The Little Millionaire"). A few years later,

in the Cohan Revue of 1918, Cohan used more songs written by Berlin. They

formed a friendship that lasted the rest of Cohan's life. After the firm of Cohan

& Harris dissolved in 1920, Sam Harris produced all four of Irving Berlin's

own "Music Box Revues."

In April of 1912 George sold special edition newspapers (printed by Hearst)

in an effort to raise money for the families of those who were lost on the

Titanic. After appearing in a revival of 45 Minutes From Broadway, he

wrote his first completely original comedy, "Broadway Jones" which he

co-starred with his mother and father. At the beginning of the show's run, it was

announced that this would be the farewell appearance of Jerry and Helen who

wanted to retire and quietly enjoy their later years together. George seconded

the motion. He announced to the disbelief of the Broadway world, that he too

was calling it quits as a performer. He would still continue to write, and produce,

but he was finished as a performer.

The team of Cohan & Harris were receiving more play manuscripts each

succeeding year. They had their pick of the best new authors, and also the best

actors. Douglas Fairbanks appeared in "Hawthorne Of The USA" (1912)

before he made his fortune in Hollywood. Raymond Hitchcock gladly returned

in "The Red WIdow" (1912), and Wallace Eddinger appeared in "The Aviator"

(1910), "Officer 666" (1912), Cohan's greatest mystery play, "Seven Keys

To Baldpate" (1913) and the long running "It Pays To Advertise."

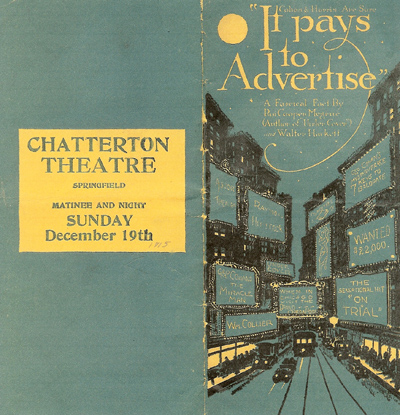

Program cover for "It Pays To Advertise" which is perhaps

where Warner Brothers got the idea for the marquee scene

in "Yankee Doodle Dandy."

The following year provided George M. with great joy. Agnes gave birth to

a son they named, George M. Cohan Jr. He would be the last child to come

into George and Agnes' life (Agnes suffered greatly during childbirth, which

caused her to be confined for most of her future).

That fall, Cohan wrote his first drama based on a con man passing himself off

as a faith healer. "The Miracle Man" starred Frank Bacon and Percy Helton,

but the film version (1919) with Lon Chaney proved to be more popular. Cohan

next went back to what he knew best, musicals & comedies.

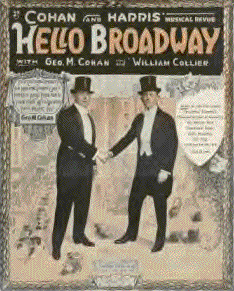

Sheet Music Cover with

William Collier

Later that year, after being prodded by William Collier at a Friars club meeting,

George returned to performing in a musical comedy, after a retirement of

10 months. "Hello Broadway" debuted on Broadway on Christmas night, and

all of New York stepped out to welcome George back (it was more review than

musical comedy - much in the Weber & Fields tradition).

Cohan assembled a fine cast consisting of Collier, Peggy Wood, Rozsika

Dolly, Sidney Jarvis, and Lawrence Wheat. The current hit Broadway shows

were lampooned by Cohan and company, with a standout performance

was by Louise Dressler (not to be confused with Marie) when she sang

"Down By The Erie." The success of "Hello Broadway" spawned two

more revue style musicals from Cohan, "The Cohan Revue of 1916,"

and "The Cohan Revue of 1918."

Cohan fiddles once

again in 1914's

"Hello Broadway"

The next year saw George cast his brother-in law, Fred Niblo in the leading role

of "Hit The Trail Holliday," a bartender that turns into a proselytizer for prohibition.

The character was loosely based on evangelist, Billy Sunday.

But nothing could have prepared Cohan for the next three years. They would be

his most turbulent years and would scar him through his final years. It began

with the death of is sister, Josie. Only a few months earlier, Josie and her

family had returned from Australia. On July 12, 1916, at the age of 40, Josie

died from complications due to heart disease. She was survived by her

husband Fred, and their 13 year old son, Fred Jr. The Four Cohans were gone

forever.

In 1916 George moved his family to a new home in Great Neck, NY. The Long

Island estate has since become an official landmark

At the beginning of 1917 George tried something different, he made his first

motion picture in Astoria, Queens. "Broadway Jones" was released nationally

on March 26, and later that year it was followed by the first film version of "Seven

Keys To Baldpate." However, Cohan didn't enjoy the filmmaking process. He

disliked filming out of sequence (a fundamental matter of economy in filmmaking),

and preferred much more, the sequence order of story-telling on the stage.

Cohan would only appear in one more film until the 1930's - "Hit The Trail

Holliday," in June of 1918.

By April, the drums of war that were resounding around the world struck America.

The European communities were already at war amongst themselves when a

German u-boat sunk the passenger ship, the Lusitania. That brought America

into the war. On board the Lusitania were such notable Americans as Charles

Frohman. America quickly became furious, and President Woodrow Wilson

(who for years debated to keep the US out of war) no longer had any choice.

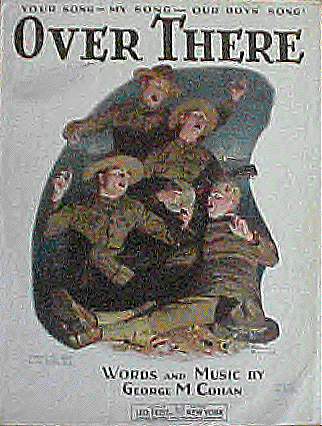

George M. wanted to do something for his country. Since he was too old to join

the military service (38), he contributed what he did best. He wrote a song and

dedicated it to "our boys." "Over There" has been credited as the greatest

war song ever written, and it is certainly one of Cohan's greatest songs. "Over

There" provided a battle cry for the naive, young, faces who were going to

go over there, and clean up the mess in a week (America was involved in

World War I for a little over a year and a half).

One of the 4 different original sheet music covers

As the war in Europe was calling for more and more of US soldiers, and George

M. Cohan was still at the top of the Broadway game, he suffered perhaps the

most severe loss of his life. On August 1, 1917, his father, Jerry Cohan, died of

arteriosclerosis at the age of 69. The grief brought on by his father's passing

was too much for the middle aged Cohan to bear. He later admitted that

immediately after his father's passing was "the only period of hard sustained

drinking in all my life." He barely had time to recover from the deep pain of

Josie's passing, and now came his father's death. George was always very

close to his father, and their relationship never wavered.

In a monthly publication of The Friars Club, Ashton Stevens recalled the

relationship between George & Jerry.

"...but the old gentlemen kept on thinking that the greatest gift in the world was

the opportunity to do a good night's work in the playhouse.

George knew. When Jerry J. forgot to talk about his next part in the next

production, George knew the end was near.

...They never thought they were doing anything irregular or unprofessional when

they dressed together - and along with George Parsons, too - in the cellar

chorus room, of Cohan's Grand, while the ladies of the "Broadway Jones"

company occupied the convenient and comfortable dressing rooms on and

above the stage."

America was conscientious about the disillusionment and despair of their

soldiers in Europe. While the Americans were helping to defeat Germany,

the loss of life, and spread of disease were beginning to erode the moral of

the young soldiers. Broadway got involved in an attempt to boost morale. The

most ambitious of these programs, was one that starred Laurette Taylor, and

was written by her husband, J. Hartly Manners, entitled "Out There." The play,

whose cast also included Joan Fontanne, was created as a benefit for the

Red Cross. For one week, and a subsequent three week tour, an all-star cast

was procured. George M., George Arliss, & Minnie Maddern Fiske, joined

Laurette Taylor in an extraordinary drive for the Red Cross. Minnie Maddern

Fiske delivered a pledge drive speech inbetween acts that was especially

written by President Wilson. Each actor appeared without compensation,

and paid for their own traveling expenses. In the one month, they raised nearly

$700,000 - a huge fortune in 1918.

Another song written for the soldiers of

World War I

With the close of World War I, audiences flocked to the theater for escape from

the tragedy of war. Cohan decidedly presented a pre-war comedy called, "A

Prince There Was" (1918) playing the lead role, himself.

The next year, after 6 months of "The Royal Vagabond" being a runaway success,

George decided to take a break, and travel by car to San Francisco. He got as

far as New Haven, CT, when something told him to stop and call Sam Harris to

be certain things were all right. It was then that he got the news. Almost all of

Broadway was shut down. The actors, in association with Actor's Equity, had

called for a strike.

On August 7, 1919 just before the new theatrical season began, Actor's Equity

staged a walkout and a dozen shows, including "The Royal Vagabond" were

shut down. One by one, the others followed suit, and in a very short time,

Broadway went dark.

George M. Cohan was furious. Even actors that he considered friends and

trusted, like Grant Mitchell, walked out on the cast of "A Prince There Was"

in Chicago. He viewed actions like this as a personal insult, and when "The

Royal Vagabond" closed, he became determined to fight the strike. The

theatrical firm of Cohan & Harris had a reputation for treating their actors well.

They were well paid (including rehearsals), and Cohan & Harris' word was their

bond. Cohan certainly knew about the abuses that the acting profession had

tolerated for many years. The fact that they wanted to put an end to these

abuses was easy for him to understand, and he stood behind that. But, that

they would include Cohan & Harris amongst the others who committed these

atrocities against the actor, that he wouldn't (nor could he), stand for.

Oddly enough, the newspapers sided with George M. The concept of unionism

wasn't nearly as popular, in the first part of the 20th Century, as it is today. Most

people viewed it (along with communism) as something anti-American. But actors

were a different breed. Even the big stars like Ethel Barrymore, and Eddie Cantor

who were always treated with respect by their respective producers (Charles

Frohman & Flo Ziegfeld) felt compelled to walk out and join Actor's Equity. It was

time for the world of the theater to change, and not even it's crowned emperor,

George M. Cohan, could stop it.

At first the producers didn't take the strike seriously. They figured that the actors,

were throwing the equivalent of a temper tantrum, and would soon come crawling

back to work. But the actors were serious, and they didn't give in on their

demands. They fought for paid rehearsals, guarantees of payment when they were

out on the road, a play or pay clause during the Christmas Holiday.

Both leading players, and members of the chorus banded together, and

demanded the issues be met. It was a coming together of scattered performers

that put the real scare in the producers. Some stars like Minnie Maddern Fiske,

also opposed Equity. Of anyone, she had the most to gain from a union because

of the years she was blackballed by the Theatrical Trust (due to her husband's

magazine, "The Dramatic Mirror," posted a bad review of one of Abe Erlanger's

shows). The two sides developed a deep hatred for one another, but the issue

of Equity put them on the same side.

A small group of actors quickly formed the Actor's Fidelity League. The express

intent of the organization was to offer a medium between the Producers and the

Actor. Such prominent actors like Minnie Maddern Fiske, William Collier, E. H.

Sothern, David Warfield, Fay Bainter, and Otis Skinner, joined Cohan in the

Fidelity League. Cohan pledged $100,000 to the League's treasury, but it was

returned (Cohan was management at the time, and it would have a reverse effect

upon getting actors to join if they thought management funded the League).

Equity bitterly opposed the League.

Meanwhile, picket lines around Broadway began singing "Over Fair" (a parody

of Cohan's "Over There"). Cohan truly felt betrayed by the actors and reckoned

them as nothing more than an angry mob. Cohan publicly stated that if Equity

won the battle, he would quit the theater and run an elevator for a living. Eddie

Cantor publicly replied, "Somebody better tell Mr. Cohan that to run an elevator

he'd have to join a union."

When hostilities grew around him, he resigned from the Friars, Lambs, and

Players Club, and withdrew from the theatrical society he loved.

Max Eastman, then a reporter for "The Liberator" magazine, summed up Cohan's

position.

"One sincere thing about him is his indignation. He is stung and hurt and angry

and a little painfully bewildered to find himself in so unpopular a position. It is

because he really had idealism and a kind of philosophy of life. It was the

philosophy of generosity and that mode of life - likeable as it may be - always

breaks down completely when it comes to a conflict between economic classes.

Friendships are disrupted, gratitude's are forgotten, generosity is rejected -

everything gives way to the formation of a clear line of conflict between the

workers who produce the goods and the capitalists who take the profits. And

George Cohan will have to readjust his whole philosophy of life completely -

so completely that he can realize that actors who owe him gratitude for

individual assistance, are right in fighting against him."

Meanwhile, at the Hippodrome on 43rd Street and Sixth Avenue, the 412

stagehands that ran the enormous show, staged a sympathy walk out. This

was the final blow to The Producer's Management Association, and on

September 6, they signed a binding contract with Actor's Equity.

Cohan again felt betrayed, this time by the producers, and resigned almost

immediately from the PMA. The negative impact of the Equity conflict would

effect George M. for the remaining twenty two years of his life. He would never

join Actor's Equity, and yet he still would produce and star his own plays. He

would often joke that he "was the only scab on Broadway," and indeed he was the

exception to the rule. Whenever he appeared with or hired Equity actors, it was

always by special arrangement.