|

Back To Film Reviews Menu

|

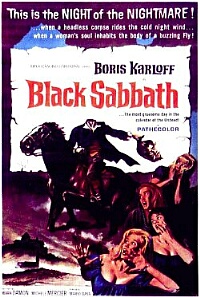

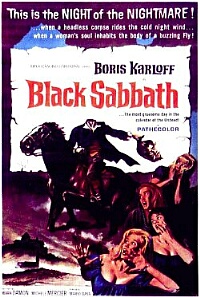

I TRE VOLTI DELLA PAURA (1963, Italian-French co-production)

Director/Cinematographer:

Mario Bava

Story: Based on "The Telephone,"

by Howard Snyder, "The Wurdalak," by Count Alexi Constanovich Tolstoi, and "The Drop of Water," by Anton Checkov

Screenplay: Mario Bava, Alberto Bevilacqua, and Marcello Fondato

Camera Operator: Ubaldo Terzano

Editing: Mario Serandrei

Music: Roberto Nicolosi (U.S. version re-scored by Les Baxter)

Alternate titles: Black Sabbath; The Three Faces of Fear; Black Christmas; The Three Faces of Terror

Aspect ratio:

1.85:1 |

Story # 1: Il telefono / The Telephone

Cast: Michele Mercier (Rosy); Lydia Alfonsi (Mary)

SYNOPSIS/CRITIQUE:

"Il Telefono" is full of fascinating touches, and marks a definite step in

the development of the giallo, yet it is frequently derided by critics

as being weak and predictable. Many of these criticisms stem from the

decision by AIP to re-write the story for U.S. consumption, but in its

original cut it is not without interest. In its emphasis on a sleazy

atmosphere filled with morally compromised people, the film anticipates

Bava's later gialli like SEI DONNE PER L'ASSASSINO and CINQUE BAMBOLE

PER LA LUNA D'AGOSTO.

The situation is simple: Rosy is a high class prostitute who is being terrorized by phone calls from her former pimp, who has just escaped

from prison. Looking for solace, she calls on her estranged lover Mary.

Little does Rosy suspect that Mary is actually behind the phone calls,

in an effort to drive Rosy back into her arms. The plan is successful,

and they spend the night together. The next morning, as Mary writes a

note explaining the situation to her lover, Frank unexpectedly shows up.

After strangling Mary to death, he sets his sights on Rosy. However,

Rosy has concealed a knife under her pillow and when Frank lunges at

her, she stabs him to death. The episode ends with Rosy reduced to

tears, and surrounded by the corpses of her former lovers. The situation is simple: Rosy is a high class prostitute who is being terrorized by phone calls from her former pimp, who has just escaped

from prison. Looking for solace, she calls on her estranged lover Mary.

Little does Rosy suspect that Mary is actually behind the phone calls,

in an effort to drive Rosy back into her arms. The plan is successful,

and they spend the night together. The next morning, as Mary writes a

note explaining the situation to her lover, Frank unexpectedly shows up.

After strangling Mary to death, he sets his sights on Rosy. However,

Rosy has concealed a knife under her pillow and when Frank lunges at

her, she stabs him to death. The episode ends with Rosy reduced to

tears, and surrounded by the corpses of her former lovers.

For the first time in his career, Bava rejects the idea of heroism in

this segment. The entire episode pivots on the idea of sexuality. The

three characters are all sexually involved in one way or another, and

the inevitable jealousy which erupts leads to violent death. Mary takes

advantage of Rosy's fears by orchestrating a series of fake telephone

calls. She assumes Franks identity, thereby establishing her as the

"male"/dominant member of the relationship, for the sole prpose of --

literally -- scaring her way back into bed with Rosy. Marys plan works,

but not without serious repercussions. When Frank returns, he strangles

her to death with one of her own silk stockings. The use of a fetish

object like a stocking makes clear the connection between violence and

sexuality. Though Bava does not adhere to close-minded, conservative

attitudes, he nevertheless recognizes that immoral behavior can lead to

deadly consequences. The primary relationship between Rosy and Frank

(i.e., prostitute and pimp) is already an unhealthy one, and Mary's role

in the triangle disrupts things even further. When he murders Mary,

Frank hisses, "Filthy bitch! You were always in my hair." Since he

clearly regards Rosy as his "property" (she is is lover, and his

"employee"), this line takes on subtle implications. Frank, the absent

off-screen "phantom," has some interesting connections to the villains

of Bava's later films LA FRUSTA E IL CORPO and SCHOCK. In the two later

films, the stories deal with women who have been shattered and driven to

insanity by domineering, sadistic males. Like those two women, Rosy is

not without sympathy. Her chief failingis that she is so easily

manipulated, first by Frank and then by Mary. The final image of "Il telefono" depicts Rosy as she lies in bed, completely wrecked by the

whole ordeal, as the camera pans past Frank and Mary. Rosy is just as

much a victim as any of the murdered people who manipulated her, and

there is no indication that her role as "survivor" is a particularly

happy one.

Story # 2: Il wurdalak / The Wurdulak

Cast: Boris Karloff (Gorka); Mark Damon (Count Vladmir D'Urfe); Susy

Anderson (Sdenka); Glauco Onorato (Giorgio); Rika Dialina (Giorgio's

wife); Massimo Righi (Pietro)

SYNOPSIS/CRITIQUE:

"Il wurdalak" tells the story of a Russian peasant, Gorka, who is transformed into a wurdalak. A wurdalak is a kind of vampire who only

drinks the blood of those they love most. When he returns to his

family, Gorka slowly infects his family, until they all join the ranks

of the undead. "Il wurdalak" tells the story of a Russian peasant, Gorka, who is transformed into a wurdalak. A wurdalak is a kind of vampire who only

drinks the blood of those they love most. When he returns to his

family, Gorka slowly infects his family, until they all join the ranks

of the undead.

The narrative is carried by Vladimir, a young nobleman who stops for the

night at a small cottage while on his way to Jassy. Like Kruveian and

Gorobec in LA MASCHERA DEL DEMONIO or Dr. Eswai in OPERAZIONE PAURA,

Vladimir is a man of reason who refutes superstition; also in common

with those other proagonists, his actions have little positive impact.

During his stay at the cottage, Vladimir falls in love with Sdenka,

Gorka's youngest daughter. She is clearly attracted to him, and warns

him of the danger. As Gorka has been gone for so long, the family fears

-- rightly as it turns out -- that he has become a wurdalak.

Predictably, Vladimir dismisses these fears as nonsense, and once Gorka

returns from his journey, there is literally no escape. Having disposed

of the dreaded wurdalak Alibek, at the cost of his own soul, he returns

to spread the contagin to his own family. Gorca's motives are hard to

pin down. At one moment he is gentle and loving, but he is capable of

brsting into a fury for little reason. One of the film's most chilling

moments occurs when Gorca reaches out for his little grandson, Ivan.

When the boy's mother holds the child back, Gorka snaps "What's the

matter, woman? Can't I fondle my own grandson?!" The implications of

pedophilia here, with the vampire/molester lusting after his own

grandson, are truly unsettling. As Gorka strokes the boy's hair as they

sit before the fire, Bava creates a perfect mockery of family harmony.

The implications of the scene do not go unfulfilled, either. Later that

night, Gorka steals the child off to the forest, where he proceeds to

drain the boy's life away. The other family members soon follow suit.

Vampirism is often interpreted in a sexual manner, for obvious reasons,

and by confining Gorka's vampirific activities to a family setting, Bava

is able to introduce elements of incest. This is pretty strong stuff,

indeed, and the depth of drama which Bava invests in the episode goes

beyond the more "innocent" genre films of the day. Within the space of

thirty-some minutes, Bava delves more deeply and more fully into the

implications which fuel the myth of vampirism than any other filmmaker

has ever dared. Gorka fits the usual image of the loving patriarch, but

his contact with evil changes him. Even so, he still seems to love his

family, the implication being that he simply wants them to be on the

same plane of existence as himself.

Unlike the other two segments, "Il wurdalak" is more expansive and

features some exterior scenes. Yet even the exteriors are drained of

life: not only are there no people around, but the land itself looks dead

and infertile. As in LA MASCHERA DEL DEMONIO, Bava insures that the

setting have a consitently gloomy look by filming on mock exterior sets.

From beginning to end, the film has the look of an expressionist

nightmare, and Bava's expert use of color is put to incessant use. To

choose the most obvious example, consider the eerie blue haze which

accompanies Gorka's return. Apart from sympbolizing the dread of the

family members, this acts as a subtle indication of Gorka's new status

as an undead, and as a foreshadowing of the film's climax, in which

death reigns supreme over the household.

Story # 3: La goccia d'acqua / The Drop of Water

Cast: Jacqueline Pierreux (Nurse Chester); Milly Monti (Maid); Harriet

White Medin (Concierge); Gustavo De Nardo (Inspector)

SYNOPSIS/CRITIQUE:

"La goccia d'acqua" is the film's last and finest segment. In fact, as a

self-contained feature, it might well be Bava's greatest work.

It tells a simple story: one stormy night, Nurse Chester is called upon to prepare the body of a deceased medium for the next morning's funeral

services. As she dresses the corpse, Nurse Chester notices that the old

woman is still wearing a beautiful diamond ring. She steals the ring

and returns home, but her guilty conscience manifests itself in

different forms: a fly, initially seen hovering around the corpse,

apparently follows her home, where it continually zones in on the

medium's ring; the sound of dripping water, first heard when the nurse

accidentally tipped over a glass of water, becomes almsot deafening to

the frightened woman; and finally, the medium herself seems to

materialze, literally scaring Nurse Chester to death. It tells a simple story: one stormy night, Nurse Chester is called upon to prepare the body of a deceased medium for the next morning's funeral

services. As she dresses the corpse, Nurse Chester notices that the old

woman is still wearing a beautiful diamond ring. She steals the ring

and returns home, but her guilty conscience manifests itself in

different forms: a fly, initially seen hovering around the corpse,

apparently follows her home, where it continually zones in on the

medium's ring; the sound of dripping water, first heard when the nurse

accidentally tipped over a glass of water, becomes almsot deafening to

the frightened woman; and finally, the medium herself seems to

materialze, literally scaring Nurse Chester to death.

Nurse Chester is motivated by greed, like so many Bavian protagonists,

but she does not go unpunished. In common with characters like Massimo

and Christina in SEI DONNE PER L'ASSASSINO, Nurse Chester is undone by a

tragic flaw. For Massimo and Christina, this flaw is an emotional one;

that is, Massimo is incapable of love, while Christina is compelled to

commit terrible crimes in search of real affection. In the case of

Nurse Chester, however, Bava presents a character whose basic morality

rebels against the act of stealing a dead woman's ring; for a person

such as this, even an apparently victimless crime can have dire

consequences. While it is possible to interpret Nurse Chester's final

fate as being the result of superstition, such an analysis does not hold

up. From the very beginning, she is well aware of the dead woman's

"ties to the spirit world," and openly mocks them. There is nothing

literally supernatural about this story. The fears which plague Nurse

Chester are born of a guilty conscience, not of other-worldly

intervention. In his later gialli, Bava concentrates on characters who

are completely free of morals. The idea of a guilty conscience is of

little consequence to these characters, simply because they have no

conscience to speak of; their downfall only derives from an increasingly

paranoid world view, in which violence is always a dominating factor.

Bava does not encourage the audience to judge Nurse Chester. On the

contrary, his aim is to force the audience to identify with her. She is

not a violent or evil person, and the fact that one petty act of

thievery affects her so badly proves that she is not a hardened

criminal. By encouraging the viewer to share in this character's

mounting hysteria, Bava's suggestion is that people -- whether basically

good or totally evil -- must be held accountable for their actions. The

apparently ghostly images that haunt Nurse Chester are in fact, like the

phone calls which plague Rosy in "Il telefono," totally harmless.

Nevertheless, the nature of fear is such that so long as one believes

what one sees, there is real danger.

GENERAL CRITIQUE:

The Italian title of this film translates as THE THREE FACES OF FEAR,

and serves as a loose representation of the three types of horror which

fascinated Bava. Each segment deals with a very specific kind of fear:

"Il telefono" deals with Bava's obsessive linkage of corrupted sexuality

and violent death; "Il wurdalak" deals with the internal destruction of

the family unity by a member who has been corrupted; and lastly, "La goccia d'acqua" concentrates on the demons of the mind, and the havoc

which they can cause.

As with any anthology, the stories vary in effectiveness. The first is good, especially in the Italian version, but it suffers from a skeletal

briefness. Bava does not have time enough to develop the storys full

potential. The second story is an honorable thesis on the vampire

mythos. The third segment is one of Bava's true masterpieces -- and its

spectacular effectiveness chiefly serves to detract from the appeal of

the other two segments. In terms of physical execution the film could

hardly be improved: the richly textured lighting, imaginative set

designs and attention to mood combine to make a visually stunning

cinematic experience, but the truth of the matter is that Bava does his

best work in single-story films which enable him to create a consistent

mood from beginning to end. As with any anthology, the stories vary in effectiveness. The first is good, especially in the Italian version, but it suffers from a skeletal

briefness. Bava does not have time enough to develop the storys full

potential. The second story is an honorable thesis on the vampire

mythos. The third segment is one of Bava's true masterpieces -- and its

spectacular effectiveness chiefly serves to detract from the appeal of

the other two segments. In terms of physical execution the film could

hardly be improved: the richly textured lighting, imaginative set

designs and attention to mood combine to make a visually stunning

cinematic experience, but the truth of the matter is that Bava does his

best work in single-story films which enable him to create a consistent

mood from beginning to end.

AIP certainly never showed any respect for Bava's work, but for the U.S.

release of this film (re-titled BLACK SABBATH) the company surpassed

itself in audacity. Bava had carefully structured the film so that he

stories would have a cumulative effect, but AIP worried that young

audiences would bore quickly if they weren't scared right off the bat.

As a result, the stories were thoughtlessly reshuffled. Roberto

Nicolosi's moody score was once again scrapped in favor of a Les Baxter

atrocity, and some of the gorier frames were either darkened or

optically enlarged to crop off the offending imagery. The second and

third segments suffer the least in translation (Boris Karloff does his

own dubbing), but "Il telefono" is changed from an effective erotic

thriller into a totally implausible ghost story.

Bava and Boris Karloff got along beautifully during the shooting, though

their relationship did have a downside. Both Christopher Lee and the

late Vincent Price recall Karloff as being very complimentary of the

director and that he was very proud of I TRE VOLTI DELLA PAURA (Lee

recalls: "I remember Boris, who did not praise lightly or easily, saying

'I would do anything for Mario Bava -- I love him!'"), but the

interference of AIP resulted in a tragedy that would deeply affect the

lives of both men. Worried that the film was going to be too intense,

Sam Arkoff and James H. Nicholson insisted that Bava lighten things up a

bit. . . on the last day of shooting. Bava's ingenious solution was to

film Karloff, in tight closeup, speeding away on horseback. Slowing

down, Karloff turns to address the audience. After finishing his

monologue, Karloff speeds off; then, on cue, Bava's camera dollies

backward revealing the whole illusion, replete with the actor astride a

rinky-dink hobby horse and technicians passing branches in front of the

camera! Bava rightly worried that the huge fans used to provide the

illusion of speed would aggravate Karloff's respiratory problems, but

the actor was so thrilled with the idea that he decided to do it anyway;

their fears were well founded, and the 76 year old actor did indeed

catch a severe chill before leaving Rome. After that, Karloff's health

gradually deteriorated and when he died in 1969, a grief-stricken Bava

blamed himself for speeding his death. As an ironic footnote, this

footage was deemed a little too relieving, and so it was not included in

AIP's export version.

Review © Troy Howarth

Back To Film Reviews Menu

|

The situation is simple: Rosy is a high class prostitute who is being terrorized by phone calls from her former pimp, who has just escaped from prison. Looking for solace, she calls on her estranged lover Mary. Little does Rosy suspect that Mary is actually behind the phone calls, in an effort to drive Rosy back into her arms. The plan is successful, and they spend the night together. The next morning, as Mary writes a note explaining the situation to her lover, Frank unexpectedly shows up. After strangling Mary to death, he sets his sights on Rosy. However, Rosy has concealed a knife under her pillow and when Frank lunges at her, she stabs him to death. The episode ends with Rosy reduced to tears, and surrounded by the corpses of her former lovers.

"Il wurdalak" tells the story of a Russian peasant, Gorka, who is transformed into a wurdalak. A wurdalak is a kind of vampire who only drinks the blood of those they love most. When he returns to his family, Gorka slowly infects his family, until they all join the ranks of the undead.

It tells a simple story: one stormy night, Nurse Chester is called upon to prepare the body of a deceased medium for the next morning's funeral services. As she dresses the corpse, Nurse Chester notices that the old woman is still wearing a beautiful diamond ring. She steals the ring and returns home, but her guilty conscience manifests itself in different forms: a fly, initially seen hovering around the corpse, apparently follows her home, where it continually zones in on the medium's ring; the sound of dripping water, first heard when the nurse accidentally tipped over a glass of water, becomes almsot deafening to the frightened woman; and finally, the medium herself seems to materialze, literally scaring Nurse Chester to death.

As with any anthology, the stories vary in effectiveness. The first is good, especially in the Italian version, but it suffers from a skeletal briefness. Bava does not have time enough to develop the storys full potential. The second story is an honorable thesis on the vampire mythos. The third segment is one of Bava's true masterpieces -- and its spectacular effectiveness chiefly serves to detract from the appeal of the other two segments. In terms of physical execution the film could hardly be improved: the richly textured lighting, imaginative set designs and attention to mood combine to make a visually stunning cinematic experience, but the truth of the matter is that Bava does his best work in single-story films which enable him to create a consistent mood from beginning to end.