Limited Edition Information

a "chapbook" given away at a party celebrating

King's Silver Anniversary in book publishing

form letter from designer Michael Alpert

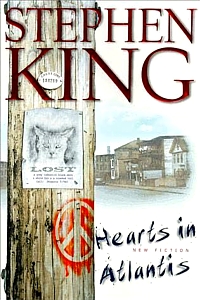

| Hearts In Atlantis |

|---|

|

|

Publication Information

Limited Edition Information a "chapbook" given away at a party celebrating King's Silver Anniversary in book publishing form letter from designer Michael Alpert |

Stephen King’s third-generation readers, maybe even second - those who came into King after he had become a worldwide phenomenon - arrived too late to be directly affected by the 1960s. Certainly they felt the aftereffects, in the real world as in King’s writing: the paranoia of government, for example, that propels books like The Stand, Firestarter, and The Running Man might not have been possible without King’s political consciousness in the 60s. But while King’s novels have long featured Baby Boomers and commentary on that generation (especially in It and Thinner), King had never directly tackled the deeper themes of what it meant to grow up in the 1960s, and how it continued to affect those who had. Hearts In Atlantis then becomes, in part, a guide map for those readers who weren’t there: a way of making sense of a time that, King argues, often made no sense at all.

The book is structured uniquely. Labeled only as "New Fiction" on the cover, Hearts is ostensibly a collection. The opening selection, "Low Men in Yellow Coats," is long enough to be a novel, while "Hearts in Atlantis," the second piece, is a novella. "Blind Willie" and "Why We’re in Vietnam" are short stories, and the final piece, "Heavenly Shades of Night are Falling," is a short-short. The pieces are solid enough by themselves, and all but the last can work independently of one another; however, it is through their interdependence that Hearts gains real power. Though the stories take place throughout different times and are seen with different eyes (as well as points of view, shifting in and out of third- and first-person), Hearts in Atlantis is too cohesive to be seen as anything but a single narrative.

"Low Men in Yellow Coats" tells a tale of 1960, when a man named Ted Brautigan moves into Bobby Garfield’s neighborhood in tiny Harwich, Connecticut. Bobby is impressed with the old man, as are his friends Carol Gerber and Sully-John. Bobby’s Mom, Liz, has her own ideas about Ted, all of which become darker as the summer of 1960 wears on. Ted teaches Bobby about adult books, in particular William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, about a group of boys who "just went a little too far." This novel and the themes within have defined much of King’s fiction. The early Bachman book, The Long Walk, features allusions and imagery directly borrowed from it. In The Dark Half, a young Thad Beaumont is so affected by the novel that he vomits upon finishing it. The name of King’s famous town, Castle Rock, comes from a location in Flies. "Children of the Corn" features an entire township of corrupted, murderous children, and both Rage and Carrie feature young people working en masse to humiliate, ruin, and in some cases murder, their classmates. Bullies of similar stripes appear in Christine, It, and "The Body" - children who take things just a little too far.

Structured as a coming-of-age story, "Low Men" bears strong similarities to "The Body" beyond the presence of childhood tormenters. Like many parents in King’s work, Bobby’s mother Liz is not entirely to be trusted. Bobby’s relationship with Ted Brautigan threatens her place in his life, and seems to directly oppose her negative assertions of men in general and Bobby’s dead father in particular. In vital ways, Liz Garfield is an echo of Regina Cunningham of Christine - a mother whose long hold on her child is suddenly slipping due to outside forces. Liz, like Regina, acts on instinct to protect herself as well as her child. In Liz’s case, her decision to turn Ted Brautigan in to the Low Men stems directly from her lack of control in her own situations with men, as well as her own half-believed impressions of Bobby’s father. Bobby’s realization that his mother has lied to and betrayed him is as powerful as Gordon LaChance’s first look at Ray Browers in "The Body".

As the first of these stories progresses, we begin to understand that "Low Men" edges into supernatural territory; diehard fans of King will begin to recognize elements of the Dark Tower series before the story spikes to its climax. However, the fact that it links with the Dark Tower books is nearly peripheral, as it had been in Insomnia and The Eyes of the Dragon. For Dark Tower readers, books such as these deepen the experience, but they remain accessible to less-versed readers, as well.

The rapid shift into six years after the first tale and into a first-person narrator in the eponymous second story, "Hearts in Atlantis," is a bit jarring at first. We meet a young man by the name of Peter Riley, a college freshman in the year 1966. Again we are reminded of Gordon LaChance of "The Body," now as an adult looking back on the experiences that shaped him and trying to make sense of them. It is Riley who reveals the explanation behind the odd title of both the story and the collection: In 1966, the Donovan song "Atlantis" was popular; Riley applies the metaphor of Atlantis to his own generation, which he fears is sinking to unrecoverable depths. This concept resurfaces in the later tale "Why We’re in Vietnam," again reinforcing the unified nature of the book.

As Bobby Garfield experiences a personal coming-of-age in "Low Men in Yellow Coats," here, Pete Reilly becomes aware of the larger world and the politics that govern it. His girlfriend, Carol Gerber (one of Bobby Garfield’s best friends in "Low Men," as well as his first kiss) awakens him to the situation in Vietnam in a way most of his classmates don’t understand. This gives him a different perspective on the twenty-four-hour game of Hearts being played in his dorm’s lounge. The game has grown into an addiction among Pete and his classmates, who play the game without regard to schoolwork or the possibility of flunking out of college and being sent to Vietnam. As elsewhere, King’s exploration of addiction here is fascinating. Though Pete and is classmates are not addicted to substances - a theme King continually returns to with new or fresh insight - the consequences of the game of Hearts are every bit as devastating.

Again, Lord of the Flies presents itself, both symbolically and literally. During one unsettling and emotional scene, Pete becomes involved in a Golding-esque mob, underlined by the contextually chilling phrase, "Man, we just couldn't stop laughing." Once again, we are reminded of Rage, in which Charlie Decker’s classmates verbally, emotionally, and physically batter Ted Jones in the novel’s climax; King would continue to explore the concept of mob mentality in Storm of the Century, Under the Dome, and Blockade Billy. Later, when Carol sends Pete a copy of the novel, he makes the underlying connections of Golding’s book and his own situation - as well as that in Vietnam - explicit.

The third tale, "Blind Willie" focuses on a minor character from "Low Men," that of Willie Shearman. Willie’s guilt over the wrongs done to Carol Gerber in that piece leads here, the story of his personal penance. Though he has been to Vietnam and saved the life of Bobby Garfield’s other childhood friend, Sully-John, he still feels a responsibility to make up for his participation in Carol’s assault. One wonders if a similar story could have been told about Victor Criss - the most levelheaded of Henry Bowers’s friends in It - had he lived.

Readers familiar with "Blind Willie," either in its initial printing in Anaetus magazine or in King’s self-published limited edition, Six Stories, will notice changes, almost all for the better. Edited somewhat to fit the larger context of Hearts in Atlantis, "Blind Willie" is now a more accessible and arguably more important work in King’s canon. Willie’s vague motivations in the original story are now explicated; atonement as a motivating factor drives the story better and helps us understand Willie as a character. As the middle story in the book, "Blind Willie" also shoulders the responsibility of linking the earlier tales and the latter; by referencing both Carol (whose importance in the previous two stories is secondary only to the main characters) and Sully-John (who becomes central to the following two pieces), "Blind Willie" succeeds.

The penultimate tale, "Why We’re In Vietnam," reunites readers with Sully-John, who we have not seen (except in flashbacks) since "Low Men in Yellow Coats." Attending the funeral of an old war buddy and while meeting up with another who is still alive, Sully is suffering his own personal hell: a long, extended trauma as the result of the horror he witnessed back in Vietnam. In the intervening years, Sully had become a used-car salesman and has made a fairly good life for himself. But he still can’t shake the memory - the everyday presence - of war. The underlying theme of "Hearts in Atlantis," that of a generation sunk, recurs; as Sully’s friend says, they are a generation who never got out of Vietnam. The phantasmagorical conclusion, in which Sully suffers a dying vision of objects representing (and perhaps subverting) the American dream falling from the sky and crashing to the ground, is King at his most allegorical.

In ways, Sully recalls two of King’s Richard Bachman protagonists: Bart Dawes, of Roadwork, and Billy Halleck, of Thinner. Halleck embodies the American dream: well-off, overweight, superficially happy. Over the course of Thinner, Billy faces the harsh realities of a society that places such importance on pretending bad things don’t exist, focusing only on the apparent, surface good. Dawes resists progress for the sake of progress, especially when it seems to be a way to avoid the memory of unpleasant realities. The opening sentence of Roadwork states: "But Vietnam was over and the country was getting on." Dawes, like Sully-John, realizes the lie inherent in that statement; facing the reality dooms them both. (Interestingly, Billy Halleck - whose only desire is to reclaim his life of superficial happiness - is also doomed.)

The concluding tale, "Heavenly Shades of Night are Falling" takes its title from the old Platters song "Twilight Time," a recurring musical theme throughout the book. "Heavenly Shades" serves as a coda to the entire volume, a gentle supernatural epilogue connecting Bobby, Ted, Carol, and Sully-John one last time, and reinforcing the themes and motifs throughout Hearts in Atlantis. While a return to the world of the Dark Tower, again, the connection isn’t distracting to readers unfamiliar with King’s series.

Hearts in Atlantis is a unique, absorbing book. Continuing a new tone set by Bag of Bones (and, to a lesser extent, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon), King’s casual voice is enhanced by a calm, literate style that sacrifices none of King’s trademark pacing or attention to character. Reinforcing his conscious move away from his "horrormeister" image, in Hearts, King has crafted a statement on a decade and a generation both subtle and nuanced, one that doesn’t feel like a statement.