|

In the early 1590s a strange figure paraded the London scene, a haughty, strutting egocentric called Shakerley. He frequented the St. Paul's Churchyard area where the booktrade was based, and his overbearing behaviour was the subject of indignant comment, which we know about because a few stray literary references have survived. Thomas Campion wrote an epigram on him, In Gloriosum; in Palladis Tamia Francis Meres refers to him in passing; and Thomas Nashe and Gabriel Harvey both try to use him as a stick with which to beat each other. Nashe began it in Strange News (1592). The point he is making is that Harvey is a fool with delusions of grandeur, an absurd attention-seeker. In fact, Nashe says, Harvey and the known fool Shakerley would make a match pair: Now do I mean to present him and Shakerley to the Queen's fool-taker for coach-horses: for two that draw more equally in one oratorical yoke of vainglory there is not under heaven.Stung, Harvey riposted in an angry sonnet which came out in October 1593. Called Gorgon, and subtitled The Wonderful Year, it describes a vainglorious character who hung around 'Powles', the great cathedral then as much a central rendezvous and gossip-shop as a church. This character strutted about, ranting on in a boastful vein like Marlowe's Tamburlaine, jeering at those weak-minded enough to give in to the plague, which in 1593 was raging with particular fury. But the plague was no respecter of persons. Despising 'his toad conceit' it struck the swaggering boaster dead. This is a year for big upsets, warns Harvey, so other empty ranters such as "the second Shakerley rash-swash" - that's Nashe - had better watch out. This sonnet appeared in 1593, barely five months after the death of Christopher Marlowe, who was both a friend of Nashe and was moreover the playwright who actually created the character Tamburlaine. Marlowe remained famous, and the absurd Shakerley was forgotten; inevitably a poem which made a reference to 'Tamburlaine' dying, and which was written in the year Marlowe so suddenly died, was in time misinterpreted. The Gorgon sonnet was long read as a reference to the death of Christopher Marlowe, and not until the late 20th century was the error corrected. In his book on Marlowe's death, The Reckoning, Charles Nicholl wrote: A single entry in a London church register provides the clue, and a careful re-reading of 'Gorgon' confirms it...Gabriel Harvey's 'goggle-eyed sonnet' is not about the death of Christopher Marlowe at all. It is about the death of a man called Shakerley...Peter Shakerley, gent, died in September 1593, and was buried in the churchyard of St-Gregory-by-St-Paul's. His funeral took place on the 18 September.Nicholl hereupon washes his hands of the Gorgon sonnet, which for those interested in Marlowe turns out to be a dead end: This tastless bagatelle of Harvey's can now be dumped, as Nashe recommends, into the 'dry-fat of oblivion'. It adds a fragment of information about the eccentric Mr Shakerley, but in the case of Christopher Marlowe is just another red herring on the trail. Nevertheless, I would like to dip into the dry-fat of oblivion myself and take out Peter Shakerley for a second look,and consider the possibility he was Peter Shakerley of Ditton, in Kent. I base this guess on five sources: Harvey's poem, the wills of Francis Shakerley and his widow Erasma, the Ditton church register and a letter by Nashe.

The likeliest origin for Shakerley of Paul's of course is that he was a Londoner. Earlier in the century there certainly had been a wealthy mercer called Rowland Shakerley. Born in Northamptonshire, his fortune was made in London, and it seems quite possible the eccentric braggart of Paul's was a connection of his. There was also a numerous and well-established gentry family of the name living in Cheshire. But Harvey's sonnet about Shakerley however contains the following line: But there is evidently another son, for whom a cautious, conditional provision is made. Francis desires his wife Erasma to: "... have consideracon and care for the mainetenance [in livinge] of my sonne Peter oute of my lease of the Mannor of Wickham St Paule in the county of Essex wch nevertheles I doe wholy refer to her motherly disposition to be temped according to his necessitye and his duetyfull caringe of him selfe towards her and his bretheren..."So Peter is not to be left to starve, if his father can help it, but his maintenance is made entirely dependent on his mother (possibly stepmother?), and is conditional on his carrying himself well towards her and his brothers. This implies two possibilities. Either Peter is a young, late child for whom a hasty provision has to be made: or he is an older child who has not always carried himself in a dutiful manner, and who cannot be trusted with direct access to money. Francis Shakerley's will was proved on 29 January 1592/3. His widow and executrix Erasma did not survive her husband very long however and her own will is made only three years later. The curious thing is that in it she makes provision for a slightly different list of progeny. Erasma still leaves property to the three named in her husband's will, making bequests to Richard (two beds, and a debt forgiven); to George (all her goods unbequeathed); and perhaps to Margaret, if she is now the married lady referred to as "my daughter Holden" who gets a silver goblet "which she hath in her custedy". But Erasma also mentions "my daughter Conisbye", who gets only a pair of sheets. Perhaps this is a married daughter, or even the product of an earlier marriage? Even stranger still is the sudden appearance of another Shakerley son not mentioned at all in Francis' will: this is "my sonne Thomas Shakerley", who receives "Thirtye shillings which he oweth me, and Twentye shillings which James Malin borrowed of me". But of Peter Shakerley, the son recommended to her motherly care by her husband, Erasma makes no mention at all. I'm beginning to wonder if this is a dysfunctional family where the parents held the financial whip hand over the children well into adulthood. What Thomas had done to merit being entirely dropped from his father's will and fobbed off in his mother's I do not know, nor who "my daughter Conisbye" was and why she got such a paltry bequest. (A witness to Erasma's will, Francis Bourman, does better than either son or daughter. Bourman receives not only a pair of sheets but fifty shillings as well. He may of course be an old and valued retainer - he also witnessed Francis' will - whom Erasma feels bound to provide for. But in that case, why didn't her husband leave him something?) Given such a puzzling scenario, and an evidently troubled family, it is perfectly possible that at the time of Erasma's will the Ditton Peter Shakerley was still very much alive but had failed to carry himself dutifully, as asked, and consequently been cut off without a shilling. On balance, though, I think it possible that he was the eccentric Shakerley of Paul's, and his mother doesn't have to provide for him in 1596 because he died of the plague in 1593. It would of course be helpful to know the birth order of the Shakerleys, but unluckily the church registers of Ditton for this period have vanished. An extract however does survive, made in the early 18th century but now available on the internet, and it contains several references to them. A Margaret Shakerley, daughter of 'Franeys' (Francis?) was baptised at Ditton in April 1567. Margaret may have been the youngest sibling, and perhaps the register had not begun at the time her brothers were christened. At any rate they do not feature in the extracts until they are parents themselves, with both 'Thomas Shakerley, gent.', and 'Richard Shakerley, gent.' having children baptised in the 1590s. The burials of Francis Shakerley and Erasma Shakerley 'vidue' are recorded, but the person making the extracts does not mention either a Peter or a George. Perhaps the original register had lost their details, or perhaps neither was buried at Ditton. George seems likely to be the George Shakerley, yeoman, whose nuncupative will of 1618 shows him resident at Plaistow in Essex: Peter I think was the Peter Shakerley buried in London twenty-five years earlier.

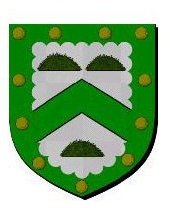

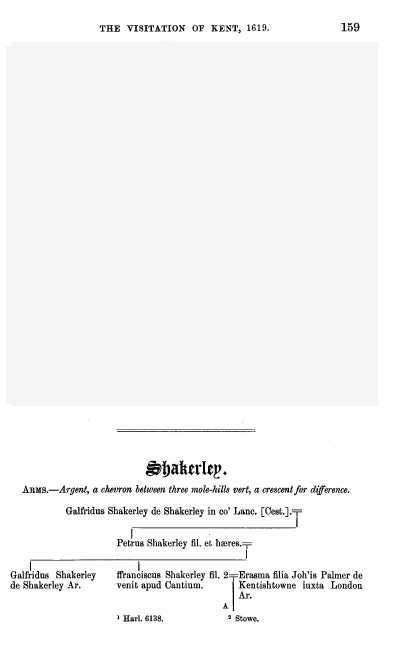

...to the house of the shakerlies that give for there armes thre doggs turds reakingWell, the arms shown above are indeed those of "the house of the Shakerleys" - the Shakerleys of Cheshire that is, whose arms unsurprisingly do not feature doggy-doo at all but molehills. In fact they are more properly described as Argent a chevron between three molehills vert, a bordure eng. of the second bezantyWhy did Nashe throw in a derisive comment about the Shakerleys? There seems no reason whatever for him to be ridiculing the heraldic device of respectable gentry up north with whom he had no known quarrel. On the other hand, it would make perfect sense for him to imply Harington's crappy book should have been dedicated to someone like the notorious fool of Paul's. It therefore seems probable Nashe's malicious allusion is to the arms borne by the dead Shakerley. So, if 'Tamburlaine' Shakerley bore the arms of the Cheshire family, was he perhaps not more likely to hail from Cheshire than Kent? Well yes, quite possibly. But fortunately for my theory there is a little genealogical hope that the Shakerleys of Ditton were a southern branch of the Cheshire family, and therefore would have borne similar arms. And this hope has been fulfilled, thanks to the wonders of the internet and the labours of Victorian members of the Harleian Society. It was the Harleian Society who in 1898 printed the Visitation of Kent made in 1619 by 'Rouge Dragon' John Philipot; and it was uk-genealogy.org.uk who put the Harleian's work on the net. As you can see below, page 159 of this Visitation refers to the Shakerleys, and shows in particular that Francis Shakerley of Kent was born in the north but 'venit apud Cantium' - came to Kent - where he married Erasma. And in due course as we know they had a son called Peter, who was entitled to bear the "three molehills" device on his arms. Frankly, that's enough for me. The mad ranter of St Paul's I think was almost certainly Peter Shakerley of Ditton.

http://www.uk-genealogy.org.uk/england/Kent/visitation/ |