![]()

![]()

The

2nd Seminole War: America’s

1st War On Terror

This

web page will delve into the Florida conflict I fondly refer to as the U.S.

Armed Forces (Army, Navy -including Marines- and Volunteers) 1st War On Terror.

I’m sure the Indians saw it from the opposite perspective, but after

all, I am a descendent of the settlers, who had a completely different skew on

the situation.

I

have delayed adding this page because I could almost do an entire other website

on the Second Seminole War at this point. Maybe

in the future, I might, but for right now, I have done my best to sum up the

Second Seminole War and the events that led to it.

I would also like to list the units in which my ancestors fought.

Problem is, they were all militia, which means, they signed up for only a

few months at a time then returned to their homes, or signed up with another

unit, or waited till their current units mustered again to fight, and I would

certainly need a whole separate web site to document them all.

To circumvent this dilemma, I am going to generalize the conflict, then,

afterwards, I may list some names, units, and battles that are already

documented.

Hope

you enjoy, and if I become too long-winded, don’t hesitate to come back

another day and finish the story. If

at all possible, please finish the story, though, because these were the baby

steps towards Florida statehood, and these early years are all important to

understanding Florida’s rich historical legacy and the struggles towards settlement.

U.S. Army Regulars with "Hog

Killer" forage caps and 1816 Springfield's.

As more people migrated to the

U.S. after the American Revolution freed the colonies from British rule, many of

the original settlers and many of the new immigrants began to move southward and

westward into the vast American wilderness. The only problem was that these areas already had

inhabitants. These original

inhabitants had resisted previous foreign militaries, and though many had become

acclimated to the presence of the Europeans, the immigration of the American

civilians into their territories was turning many minds again to war.

There was also a large population of escaped slaves in Florida.

The name “Seminole” itself means “runaway” as the Seminoles were

made up of remnants and runaways from other tribes, and though some Seminoles

took the escaped slaves as their own, most of the runaway slaves were more

like indentured servants. The Seminoles allowed them to live alongside as long as the

Africans contributed portions of their crops and livestock to the Seminole

community to which they were joined. Many

of these Africans adopted the ways of the Seminoles, intermarried, and are actually referred to

as Black Seminoles.

As the United States went to

war with the British in the War of 1812, the Seminoles and escaped slaves were

armed by the Brits, trained as guerilla fighters, and encouraged to make raids

on the farms of American settlers in Florida and some outside of Florida.

Because of this alliance, the U.S. government turned an angry eye towards

the Seminoles. Also, pressure was being brought to bear from the powerful

plantation families, as the government was in charge of rounding up escaped

slaves and returning them to their legal owners. This was becoming a large problem as the importation of

African slaves had recently been outlawed and the supply of human laborers was

dwindling. Or, so said the

slave owners.

Not until the ending of hostilities (at least officially) with the British did the U.S. military turn its focus to the Indians. The First Seminole War was fought, as well as engagements with other tribes. And though these tribes, who signed peace treaties to end the fighting, continued to fight throughout the ‘teens and ‘twenties, many American families, encouraged by the government, began to head south.

These pioneering families moved into Florida and cut farms out of the scrub. Spanish cattle roamed wild, “free” for the taking, and the pioneers tried to make friends with the native populations when possible. Truly, the pioneers had a more formidable enemy than hostile Indians. As the Spanish had almost completely wiped out the natives of Florida in their conquest of the Americas and their frenzied search for gold, the climate of wild Florida wiped out many of the arriving pioneers. But the Spanish left Florida in 1819, and eventually the pioneers learned to deal with the climate. Happy days are here again? Not if you know human nature.

Chief Abraham (right) and wife Hagan (left).

Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe,

President James Monroe, and his Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams, came to

an agreement with the European powers. This

“Monroe Doctrine” (December 1823) basically stated that the Western

Hemisphere was to be free of the European monarchies and any attempts by Europe

to establish colonies in the Americas, would be considered a direct threat to

the United States.

The U.S. was now a world power to be reckoned with, and few countries

would dare to ever again threaten her soil.

Of course now that the threat of outside intervention was dealt with,

America’s sense of “manifest destiny” became a thirst.

Like-minded immigrants were pouring into the States, and many were

looking to make any land grab possible.

The wilds of Florida were ripe for the taking, but clearly, a mass influx

of white settlers would be resisted by the Seminoles who were already being

pushed further south than they liked. Florida’s

governor, Wm. Pope DuVal, and an Indian Agent, Colonel James Gadsden had already

parleyed the Treaty of Moultrie Creek [Moultrie is a small town just outside of

St. Augustine where my great-grandparent’s old homestead still stands].

This treaty agreed to give livestock and farming implements back to the

Seminoles, much of which had been taken from them at the end of the First

Seminole War. It also agreed to subsidize them with food and money as long

as they agreed to remain within the allotted reservation of land and behave

themselves, but they also had to agree to their eventual removal to reservations

west of the Mississippi.

Eventually, the U.S. Supreme

Court voided the treaty having decided the Indians had no right to the land as

the property belonged to the U.S. by right of discovery.

The Seminoles were more than happy to agree to this- in a pig’s eye.

First off, they may not have been the aboriginal people, but seeing as

the Spanish had slaughtered the previous inhabitants, the Seminoles felt they

had inherited the land. Secondly,

the Americans had not discovered the land.

They had taken it basically by coercion from the Spanish (i.e. “Seeing

as we’ll likely take the territory by force if you do not capitulate, you had

better take our offer to forgive your debts to our treasury in exchange for that

mosquito-infested swamp… which neither of us really wants anyway, ahem,

ahem”). And lastly, the United

States had made the offer in first place, and it was hardly a fair one.

The Seminoles hadn’t really

kept their end of the bargain, either. Though

various leaders made treaties, segments of their population continued to

terrorize the white settlers and taunt the U.S. Military.

[For a modern reference, the situation with the Palestinians in Israel very closely mimics the

early decades in Florida. Fortunately,

the Indian warriors had a firmer grasp on their own self-worth and no high

explosives.]

Osceola, Seminole War Chief.

In the early 1830’s,

President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act passed Congress. Jackson, having been a leader in the War of 1812 and later a

provisional governor of Florida, held an extreme distaste for Seminoles.

After the Seminoles had signed and reneged on both the Treaty of Paynes

Landing and the Fort Gibson (Arkansas) Treaty under protests of coercion,

Jackson lost his patience and ordered the Seminoles removed from Florida by

force, even though strongly cautioned by the current Florida governor, John

Eaton.

In April 1835, Indian Agent

Wiley Thompson and Colonel Duncan L. Clinch, the President’s personal friend

and commander of the Florida forces, called the leaders of the Seminole tribes

to Fort King for yet another parley. They

produced the Treaty of Fort Gibson and demand the leaders comply with the

previously signed document. Rage

erupted from the chiefs who said their representatives had been “boozed up and

tricked” [my words, not theirs] into signing the treaty, and it would not be

honored!

Present at the treaty was a

young war leader called Osceola. Born

in Alabama, he was raised Billy

Powell, after his father/stepfather (it is still in question whether Osceola was

Powell’s son or the offspring of a previous Creek marriage), a Scottish

trader, and his Creek mother.

He and his mother were reportedly removed to Florida after the Creek War,

and he learned to fight during the First Seminole War.

Osceola was cunning and fiercely loyal to the Seminoles, and he

immediately began to make a name for himself within his newly adopted tribe.

Osceola may not previously have

been known outside his tribe, but he became instantly infamous the day of the

Fort King meeting. According to

legend, when the chiefs were ordered by Colonel Clinch to sign the removal

papers, he leapt to the document on the table and drove his knife through it

proclaiming, “This is the only way I sign!”

Osceola was immediately ordered

shackled by General Thompson, and though he was released when the meeting was

adjourned, he returned a few days later to argue again with Thompson.

And again he was thrown into shackles, but this time, the Indian agent

did not release his prisoner. As a

matter of fact, Osceola was held until he later convinced those in charge he had

had a change of heart and was going to talk his fellow Seminoles into giving up.

He had obviously learned his lesson, and was set free to return to his

people. Big mistake.

General Duncan Clinch.

Meanwhile, settlers continued

to have disputes with the Seminoles, and one day at Hickory Sink outside of

modern Gainesville, FL, a fight broke out between local Seminoles and members of

a Florida militia unit. The militia

were trying to help a resident find his “rustled” cattle, when they came

upon a couple Indians roasting a side of beef.

Dispensing a little frontier justice, they began to beat the Indians and

whip them with their “cracker whips” [see front page of website].

Hearing the commotion, the rest of the hunting party returned and a

gunfight ensued. At least two of

the militia were wounded, one Indian was killed and another wounded.

In retaliation, mail carrier

Pvt. Kinsley Dalton was killed on his route between Fort Brooke and Fort King,

August 1835. He was the first U.S.

soldier killed in the conflict, but not the last as many from his own brigade

were to be killed later at the Dade Massacre.

Following the killing of Pvt.

Dalton, the forcible removal of the Seminoles was begun in earnest.

Most were interred at Fort Brooke in Tampa, but those who cooperated with

the government were allowed to retain their property and continue trade with the

white settlers. [One of these was a personal acquaintance of my ancestor J.D.

(John David) Osteen. Chief Charley

Emathla’s tribe lived somewhere between Newnansville (where J.D. lived) and

Chiefland (where many of my later ancestors lived). Early Levy County land records also refer to “Charlie

Emathla’s Town” though, to my knowledge, the exact location of the village

is not currently known.]

Charley Emathla was one of the

signers of the original Treaty of Moultrie Creek, and he continued to trade with

the whites until his people’s planned removal to Arkansas courtesy of the U.S.

government. Returning from a

livestock sale initiated by Indian Agent Wiley Thompson, Chief Charley was

ambushed by Osceola and his war party. The

Indian chief was butchered and according to legend, the money from the sale was

strewn about his body as a warning to Seminoles who wished to emigrate

peacefully.

This sparked an all out

uprising as war parties began raiding small farms and plantations.

December 7, 1835, the Florida militia fought the Seminoles near the

plantation home of Captain Gabriel Priest near Archer (just outside Gainesville)

and later the same day, miles to the east, there was another attack on a logging

party at Drayton’s Island [a large lake-island at the north end of Lake George

about 14 miles south of Palatka- “Plak-er” if you’re a “cracker”].

The first official battle of the Second Seminole War occurred a week and

a half later, again near Archer.

Governor

(and General) Richard K. Call.

General (later Governor)

Richard Keith Call, had come to Florida as a personal aide to Andrew Jackson. He

eventually made Florida his home, and now led the Florida militia.

General Call had heard of the recent attacks around northern-central

Florida. He ordered a detachment of

mounted militia under a Capt. Richards, to escort a logistics train to Micanopy

to supply Colonel John Warren via the “old Spanish Highway”.

Though often referred to as the

Battle of Kanapaha Prairie, or “Black Point”, as with many of the

engagements of the Second Seminole War the battle was more of a skirmish.

See, the Seminoles were hit and run fighters, and were thus able to draw

what would have been a quick battlefield victory for U.S. regulars and militia

into a protracted guerilla war. Anyway,

as the logistics train reached Black Point at the southwestern corner of the

Kanapaha Prairie [around S.W. Archer Road south of Kanapaha Botanical Gardens,

if you know Gainesville], they were attacked by a Seminole war party.

Most of the unseasoned militia fled at the first shots, including Capt.

Richards.

A few men stood their ground,

but after one was severely wounded, they loaded him on a cart and retreated to

the cover the other militiamen had quickly discovered.

At one point the Seminole warriors tried to intercept the retreating

cart, but several were killed and they were forced to return to cover.

The poor carthorse took several musket balls, but he managed to tow the

cart and wounded man to cover before he collapsed- dead.

By this time, the rest of the

attachment, under a Captain Lemore, arrived to find the Indians ransacking the

supply caravan and Richards and his men firing random shots from cover.

Richard’s men had attempted another attack but were quickly repelled

and had resigned themselves to awaiting their reinforcements.

Capt. Lemore ordered his men to charge the Seminoles, but only half

obeyed. Fifteen horsemen charged

the wagons, and of those, six were killed and eight wounded.

At this point, the remaining

contingent felt it better to retreat to Fort Crum [located on the western edge

of Paynes Prairie, this ill-fated fort was eventually overrun by the Seminoles

and all but one of its inhabitants were killed] for reinforcements and medical

attention. On their return they

found the wagons gone, but several days later, a portion of the wagon train was

relocated and liberated from its captors.

Chief

Billy Bowlegs and son.

News spread quickly through the

Seminole tribes of the actions near Kanapaha and Wacahoota [around 5 miles south

of Gainesville on SW Williston Rd for those of you familiar with the area], and

the whole of north-central Florida became a danger zone.

Almost every plantation and settlement to the immediate south of St.

Augustine were attacked and/or destroyed, and elsewhere across the state,

settlements and farms were being burned and their residents slaughtered.

The attacks sent the entire

state into a panic. Duncan Clinch,

now a general, was currently at Fort King and was making plans to move his

troops from the fort to his plantation “Auld Lang Syne” (later renamed Fort

Drane after fortifications completed) just south of Micanopy.

He ordered reinforcements sent up from Fort Brooke (Tampa), and the

troops under command of Major Francis Dade set out immediately believing Fort

King to be under siege (although this was not the case and the move was being

made for logistical reasons).

Approximately five days into

the march (Dec. 28, 1835) the detachment of 100 men and eight officers reached

the edge of Wahoo Swamp. So far the

Fort King Road had been hospitable, but this was an area rife with hostiles, and

the soldiers were anxious to move north of the ancient hammocks of Wahoo Swamp.

Little did they know their guide/interpreter, Louis Fatio Pacheco, a

multi-lingual slave from Fort Brooke, had already sealed their fate.

The Seminole War Chiefs Jumper

and Micanope had received warning from Pacheco at the outset.

Seminole braves had shadowed the detachment for days, and had noticed the

troops were rather unready for war and were marching in loose formation.

The chiefs also knew the soldiers would be very wary of the Wahoo Swamp

as the thick canopy of trees looked spooky and menacing even at face value, but

they would certainly lower their guards once they cleared the swamp and entered

the “safety” of the pine barrens north of the swamp.

The chiefs were exactly

correct, and the troops’ sighs of relief, having finally exited the

frightening swamps, turned to cries of terror as almost 200 Indian warriors

opened fire on them from their palmetto covers.

The officers tried to bring the artillery to bear, while several soldiers

manufactured an impromptu breastworks, but many of their fellow soldiers had

been killed before they could even fire a shot.

Of the 109 men who had exited the swamp, only two soldiers had escaped,

as well as their “guide” (and friendly host) Louis Fatio Pacheco.

The Dade Massacre was one of

the worst slaughters in U.S. Army history with 97% of their force KIA.

And as if this would not have been enough to provoke the dogs of war,

Indian Agent General Wiley Thompson, unaware of the massacre which had taken

place earlier that day, had just finished dinner at Fort King.

He decided to take a leisurely stroll outside the fort, and may have

thought differently had he known the fate of the soldiers who were scheduled to

reach the fort on the following day.

The quiet evening erupted in

gunfire. Soldiers at once grabbed

their weapons and went to meet the attack.

To their horror, the only thing they found was the mutilated body of

General Thompson, scalped and riddled with bullets and knife wounds.

Osceola had extracted his revenge.

Only three days later, General

Clinch and his force from Fort Drane along with General Call’s mounted militia

forces converged on Osceola, and his ally Chief Alligator (Halpatter-Tustennuggee),

at the Withlacoochee River. The Seminoles had escaped to the opposite bank of the river,

and the only means found to cross the river was a leaky canoe.

Before a large number of the regulars could traverse the river, they came

under fire from the Seminoles who had become aware of their presence.

While an enormous force of militia and regular army soldiers stood

helpless on the opposite bank, Seminoles and Negroes rained fire on the

soldiers. After a succession of charges by the regular troops, the

Seminoles were in sufficient disarray to allow more forces, regular and

volunteer, to cross the river. With

the addition of these forces, the Seminoles were driven back, and General Clinch

decided to collect the large number of wounded, and few dead, and return to Fort

Drane.

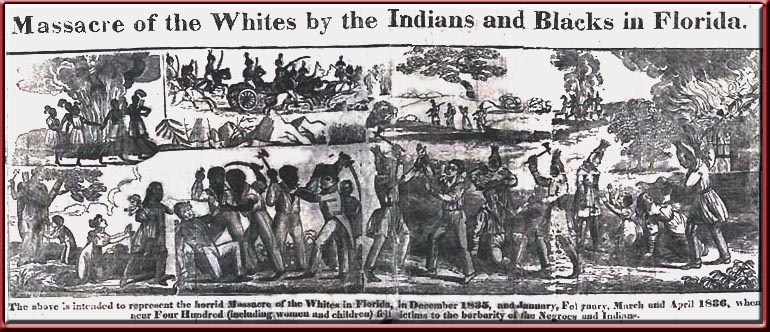

Northern newspaper portrays numerous attacks

during the period between Dec.1835 and Apr.1836. Such raids

continued for years.

[A brief word about Chief

Alligator and an incident, which happened in my family history.

The town of Lake City, FL, where I was raised, was established near the

site of an Indian village called “Alpata Telophka” or “Alligator Town”

after the chief. This was told to

my 5th Great Grandfather J.D. (John D.) Osteen by Bill and Charley

Emathla {Spanish Land Grants in Florida, Vol. I-II, p 60, Claim a-27}.

J.D. lived about two miles east of Alligator Town alongside his brother

James Osteen. J.D.’s

brother-in-law, Allen S. Parrish, son of Captain Josiah Parrish, actually lived

and farmed on the site of the old village.

As I understand it,

J.D. and his son Allen were away with the militia. J.D. had sent his wife, Martha J. Parrish Osteen,

and their other children to stay with his brother, Captain James Osteen, and

sister-in-law Argent Cason Osteen.

This probably seemed a secure location for his family since his brother

James had founded one of Florida’s first militia units in 1826 and had been

fighting Indians ever since.

Unfortunately, this Tuesday,

May 28, 1839, about sundown, the farm came under attack from a raiding party.

James fought the Indians while his pregnant wife and the children fled to

the nearby plantation of their relative, Captain Zachariah R. Roberts

(another militia Indian fighter). Martha

had been shot in the arm and side and lay bleeding.

A visiting family friend,

Simeon Dell, was working in the stable when the fighting started and ran to the

house for a weapon. Looking

outside, he saw James dead on the ground in front of the stable and the Indians

approaching. As he had yet to find

a gun, he hurriedly stuck a broom handle out the door opening to look as if he

was about to fire on the raiders. The

Indians fled to the tree line, but hearing no gunfire they again returned to the

house in time to discover Simeon was now armed for real.

A brief firefight ensued, chasing the Indians from the property, but not

before Simeon had received a bullet in his chest which lodged in his shoulder.

These Indians proceeded to the Asa Roberts’ (yet another Indian fighter) farm down the road. Asa Roberts' wife had died a few years prior, and Asa was now raising their young children on his own. He, having heard the gunfight a quarter mile away at the Osteen's, had quickly gathered his children and fled by foot to his father Captain Zachariah (or Jack) Roberts’ plantation for safety. Finding the home abandoned, the raiding party pillaged the Asa Roberts’ farm, stealing all they could carry and his only horse, and burned the rest.

The booty laden raiders fled before the militia arrived to facilitate their capture, but it wasn't long before the vengeful Roberts men and other local militia were on their trail. Most of the raiding party escaped, but two did not and were buried outside the fence of the cemetery where Captain Jack Roberts laid to rest his friend James Osteen.

At the Osteen farm,

Martha and Simeon Dell were found wounded, and of course, James was dead, but

they both survived and the children had escaped.

Therefore, I and many of my cousins are here today, and I am certainly thankful for the brave

acts of James Osteen and Simeon Dell.

Now this is the way I heard the

story. If any of my cousins out

there, Parrish’s or Osteen’s, know anything different, or have anything to

add, please let me know. A niece of

Simeon Dell wrote to her family in Savannah about the attack. The Savannah

Georgian printed a story on the murder of James Osteen entitled "More

Indian Butchery", and the article was reprinted in the national newspaper

the Niles' National Register of Baltimore on June 15, 1839.

In conclusion to this story, as

if life wasn't hard enough in the Florida wilderness, Argent Osteen had lost her

husband and Asa Roberts had lost everything but his children. The two

eventually found comfort and relief in each other, and the widow and widower were

soon married. Asa Roberts raised the Osteen children as his own with

support from their two influential families (well, three when you include the

Cason's). James' two

oldest sons also served in the militia during the Seminole War, and the youngest

Osteen son became a lieutenant in the Confederate Army where he gave his own life on

the altar of Southern freedom. The

baby girl was born five months after her father’s death.

Cassa Osteen eventually married a schoolteacher who distinguished himself

in Confederate service, and their son became a state senator.

All is well

that ends well.

In addition, one of Argent's

surviving children founded the town of Osteen in Volusia, and you can see a

picture of J.D. and Martha’s grandson, Solomon Osteen, on my 1st

Florida Special Cavalry page.]

Chief

Micanope, a powerful Seminole leader.

Colonel R.C. Parish’s mounted

militia fought with a large party of Seminoles near Watumpka in Gadsden County

(named for Capt. James Gadsden, Army Engineer of the 1st Seminole

War). Watumpka was the site of the

U.S. Arsenal constructed in 1834 by the Department of the United States Army

Ordinance. The mounted militia

repelled the ambush at Watumpka, but the reverse happened at the Dun-Lawton

Plantation Sugar Mill and Rum Distillery on the Hallifax River [near Port Orange where you can

still visit the large cane press]. Chief

Coacoochee defeated Major Benjamin Putnam’s “Mosquito Roarer” militia, who

even after heavy fighting were unable to save the settlers’ homes, the

distillery, and the

sugar mill from being looted and burned.

Having suffered more defeats

than victories won (some of which are omitted here for brevity), the

Floridian’s begged President Jackson to send more regular army to assist them.

Not only did he not send immediate assistance, he became down

right belligerent and insulted the Floridian’s, stating that he and 50 women

could have whipped every Indian in the state.

Adding to the insult, he said the Floridian’s might as well let the

Indians kill them, so their women could find new husbands whose offspring might

be brave enough to defend their own country, and replied to the request, “Let

the damned cowards protect their own country.”

For obvious reasons, the

Floridian’s, who were enduring such hardships, and fighting much of the time

for no pay (General Call ultimately penned a formal letter of protest stating the

government was cheating his militia out of their due pay), were infuriated by

the President’s words. The

Florida Herald published their reply in March of 1837:

“We belong to no political faction, have few party predilections, and neither fear the frowns of the court, the smiles of the Whig or democrat; but we belong to Florida…. Our character and interests are identified with hers; and no man, or set of men, however, high in office, or any party, shall trample with impunity upon her rights, or wantonly on her honour, without receiving merited censure.”

In other words, “President or

no, you had better watch your mouth.”

After publishing the letter, a

party was held in dishonour of the President. Speeches were made repeating their disgust with the current

administration, and to boot, the ladies gave a toast in honour of their men,

basically saying regardless of Old Hickory’s insults and statements to the

contrary, they were quite content with the men they had.

The military blundering

continues even after the illustrious General Winfield Scott is sent to Florida

to take command. He and General

Edmund Pendleton Gaines (famed for his arrest of Aaron Burr, the Vice President

who killed Alexander Hamilton) squabble over control of the Florida troops, and

continue to suffer defeats in the meantime.

The ongoing Creek War is clearly a distraction to Scott, who also

quarrels with General Thomas Sidney Jesup who had been sent by President Jackson

to assist in command of the Georgia based troops fighting the Creeks and the

Florida based troops fighting the Seminoles. Talk about too many chiefs, too few Indians…

General Winfield Scott.

General Call is made

Provisional Governor of Florida much to the joy of the militia who served under

him, and he is soon placed in charge of all Florida forces.

And though, a number of U.S. Army forts, like Fort Alabama (rebuilt as

Fort Foster, located northeast of Tampa), were being overrun by the Seminoles,

the Georgia and Florida militias were meeting with some success against the

Creeks and Seminoles in the north. Under

Gen. Jesup, Col. John Warren’s regiments around Columbia County earned

commendations for their victories in the Okefenokee Swamp.

The mounted militia engaged in constant firefights along the

Georgia-Florida border and managed to capture and kill many of the Creeks who

were fleeing Georgia and Alabama to join their Seminole brothers to their south.

Many of the Creeks decided to

adopt the “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” stance and signed on to

interpret and fight for the U.S. Army. A

couple of these were sent out one rainy evening in September 1836 to reconnoiter

the area south of Newnansville, where earlier that day, five men had come under

fire while gathering corn. These

“spies” located the attacking Indians deep in the San Felasco Hammock.

The next morning, Col. Warren

and his militia, accompanied by a detachment of regulars and artillery, rode out

to meet the Indians. They entered

the hammock in three columns and were immediately attacked on their right.

The Indians fought tenaciously that day making at least two charges on

the cannon, but their difficulty, as with other engagements, was that so few were

trained in the military use of firearms and tactics.

Often, the Indians would use

musket balls incorrectly sized for their weapons, as well as firing

foreign objects. Frequently they

would pour powder down the barrel in unmeasured amounts, then stuff a ball in

the top of the barrel without correctly seating the ball with a ramrod.

This would cause the ball to spin wildly off target when fired, or

depending on the amount of powder, the ball might not have enough velocity to

puncture the heavy clothes worn by the soldiers they were fighting.

Some soldiers recalled seeing their fellows leap into the air to catch

Indian fired musket balls in their bare hands, thus demonstrating the low

velocity produced by an improperly loaded musket.

These factors outweighed the Indians obvious superiority at stealth and

stalking, which meant they constantly surprised the soldiers, but rarely did

more than wound those they had surprised.

One tall Indian on horseback

drew the fire of an entire company as he rode down the line directing the

Indians to attack, but even though shot from his mount in plain sight of the

troops, neither he nor any of the others were found after the Indians were

driven back into the hammock. Witnesses

stated the ground was covered in blood, but no bodies found.

The fight had lasted well over an hour with sustained fire throughout,

and there was no body count. Fortunately, none of the soldiers were killed and only a few wounded.

So ended the Battle of San Felasco Hammock, but there would certainly be more to come.

General

Thomas Sidney Jesup.

The Army and Florida militia

began to push the Seminoles, led by Chiefs Osuchee (Cooper) and Yaholooche

(Cloud), down the Withlacoochee River, back into the Wahoo Swamp.

General Robert Armstrong and General (Governor) Call had been joined at

Fort Drane by a large compliment of Creek militia who under the leadership of

their Chiefs John O’Poney, Jim Boy, David Moniac, and Paddy Carr had been

sworn in as volunteers and placed under the command of Colonel John Lane.

Colonel Lane, like most of the soldiers who died in the conflict,

succumbed to illness, though. He

died soon after reaching Fort Drane, and his command was passed to Lt. Col.

Harvey Brown. But this did not stop

the Creeks, and the sight of hundreds of red and white turbaned (which they wore to

distinguish themselves in battle) Indians marching to fight on the side of the

white men, infuriated and intimidated the Seminoles.

I’m sure seeing the detachment of over 500 Tennesseans who had arrived

to reinforce Fort Drane did not bring the Seminoles great joy either.

After some fierce fighting

around the outskirts of the swamp and in the area of Dade’s Massacre, the Army

generals were looking to make a decisive strike. Only a day or so earlier, the soldiers, who were concentrated

on the eastern bank of the Withlacoochee, had been attacked by a large force of

Indians opening fire from the opposite bank.

General Call had decided to pull back towards Volusia to re-supply.

Notably, during this fight, the now famous Major (Chief) David Moniac,

who to that time was the only Native-American (actually of mixed heritage, since

he was part Scottish, Dutch, and English as well; and interestingly, he was

married to Osceola's cousin, Mary Powell) to have graduated West Point, was

killed while trying to locate a ford for his Creek troops to cross and

counterattack the Seminoles on the western bank. He had received his

promotion to Major only a week prior.

Dawn of November 21, 1836, a

large force including Col. Warren’s 1st Florida Mounted Militia,

Major Gardener’s Middle Florida Volunteers, Lt. Col. Brown’s Creek

Volunteers, Col. Henderson’s Tennesseans, as well as the U.S. Marines and U.S.

Army infantry and artillery closed in on the Wahoo Swamp. War whoops erupted from the hammock rimming the swamp, and

Seminoles could be seen in mass along the edges.

The troops broke into battle

formation and approached the swamp while calmly holding their fire until they

were on top of the Seminoles, then opened a fearsome fire.

The battle raged for much of the day with incursions into the swamp.

But, in the swampy mire, the officers struggled to keep form, and often

had to withdraw to regroup.

Basically, there was no clear

objective beyond “meet and kill the enemy”.

The 200 Negro rebels, 400 Seminole braves and their families who had been

living in and around the Wahoo Swamp were either forced deeper into the swamp

where they couldn’t be reached, or were driven across the Withlacoochee where

the soldiers would not follow for fear of drowning (even though unbeknownst to

them, the black waters of the river were only 2-3 feet deep in most areas, thus

the easy escape of the knowledgeable Indians and Negroes).

The official report described the action as a resounding victory because

of the brave and relentless fighting of the men involved.

In the larger scheme, the engagement had accomplished little other than

the thinning and dispersal of the enemy. Beyond

that the troops had gained more battle experience, quite a few injuries and very

hungry bellies (the battle was a logistical nightmare, supplies falling far

short of the food and ammunition required, and following the battle General Call

is replaced by General Jesup as commander in Florida).

In 1837, the tide began to turn

against the Seminoles. At this

time, the United States was in its first big depression due to Jackson’s

reckless economic policies. The

election of former Vice President Martin Van Buren as President did not help

matters, but Florida, still a territory, was not receiving much federal aide

anyway, and her residents were mostly self sufficient.

Fortunate for the Indian fighters with President Jackson being replaced

and the former Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army heading the Florida

forces, a steady influx of soldiers and supplies was trickling into the

territory (although the militia was still having difficulties claiming their due

pay). As a matter of fact, by the

end of the year, over half the U.S. Military would be located in Florida.

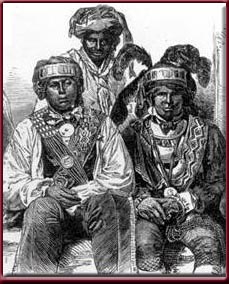

Chiefs

Jumper, Abraham, and Bowlegs (from left).

The Seminoles were also losing

leaders. John Caesar, advisor to

King Phillip Emathca (Black Seminole chief and brother-in-law of Chief Micanope),

and his group attacked the Hanson Plantation (a mile and a half outside St.

Augustine on the St. Johns River). The

St. Augustine militia caught Caesar in camp that evening, killing him and a

couple others. A few days later,

almost the same scenario happens near Lake Apopka and Chief Osuchee is killed.

Chiefs Jumper, Micanope, and

Abraham (Abraham was a Black Seminole Chief, who served as interpreter to

Micanope and was married to Chief Bowlegs widow, Hagan) called a stop to the

fighting. But other chiefs ignored

them, as up to 400 Seminoles and Negroes, including Louis Pacheco, under King

Philip and Chief Coacoochee (King Philip’s son), attacked Camp Monroe [on Lake

Monroe -the body of water you cross on I4 before entering Volusia Co. from

Orlando]. The camp was later

renamed Fort Mellon after Captain Charles Mellon who was killed at the battle,

and settlers named the surrounding area Mellonville [now part of Sanford, around

the modern Fort Mellon Park site].

Finding only moderate success

against the Seminoles, General Jesup again parleyed with the Seminole chiefs.

Agreements were reached, and many of the Seminoles began to turn

themselves in at Fort Brooke for relocation.

By May 1837, over 700, including Chiefs Micanope, Jumper, Alligator, and

Yaholooche, awaited transport to the West, but Osceola had other plans.

Due to changes made by the whites after the agreements were made, or so

said Osceola, the

Seminoles were no longer accepting the deal. And when he and 200 warriors

arrived at Fort Brooke, the soldiers inside were more than happy to let their

wards be on their way. As many as 900 Seminoles and their Negro counterparts faded back into the Florida

wilderness.

General

Joseph Hernandez.

Infuriated by having been so

close to his goal, and now so far removed, General Jesup resorted to the

longstanding, though under appreciated, tactic of treachery.

General Joseph Hernandez, leader of the St. Augustine militia forces, had

captured King Philip, Coacoochee, and Yuchie Billy near the abandoned Mosquito

Inlet [now Ponce De Leon Inlet]. The

chiefs and their men were imprisoned at Fort Marion [the Castillo de San Marcos

in St. Augustine], and Gen. Jesup let it be known they would be hanged if the

other Seminole leaders did not surrender.

Gen. Hernandez sent a prisoner to contact Chief Osceola and set a meeting at

Moultrie Creek, the site of the newly constructed Ft. Peyton (built near the site

of the Treaty of Moultrie Creek signing). Osceola

and his compatriots were on the road to Ft. Peyton under the flag of truce when

they were met by Gen. Hernandez's men and immediately placed under arrest and imprisoned at Fort Marion [many years later,

the famous Warrior Chief Geronimo was also imprisoned at Fort Marion for eight

years]. General Jesup defended his actions by reiterating that the

Seminoles were in violation of the treaties they had signed, and his answer to

detractors was simply that he had offered no parley, and any Seminoles arriving

under white flag were simply surrendering.

The Seminoles at Ft. Marion

immediately hatched a plot to escape. They

began a hunger strike to starve themselves thin enough to slip through the bars,

actually killing Yuchie Billy only days before the daring escape.

[Having been to the Castillo de San Marcos (Fort Marion) many times (St.

Augustine being the town of my birth), I am still amazed at the daring escape.

You would do well visit the beautiful fort and site of the escape.

I can guarantee, you’ll get chills thinking of it.]

November 27, 1837, Coacoochee,

John Cowaya (Black Seminole leader), sixteen braves, and two women slipped

through the bars of their cell, and managed to escape over the moat to freedom.

Immediately, they headed south to join Chiefs Alligator, Arpeika, and

Jumper and prepare for what was to be the largest battle of the Second Seminole

War.

The Battle of Lake Okeechobee.

Colonel Zachary Taylor was

dispatched from Fort Brooke with the largest collective force of the war.

General Jesup was fed up with the guerilla tactics that had served the

Seminoles so well and was determined to crush the Seminoles with overwhelming

odds [compare the drawn out debacle in Vietnam to the current Iraqi conflict].

Christmas Day, 1837, the force converges on swamp surrounding Lake

Okeechobee, but as was the case in the Wahoo Swamp, the regimented formations of

the U.S. Army did not work in the muck and cypress hammocks of the Okeechobee

and heavy losses were suffered as a result.

Still, Col. Taylor’s men were able to drive the combined Seminole and

Miccosukee force from the swamps, and General Jesup finally had his victory.

[In appreciation, Colonel Zachary Taylor was promoted to General due to

his triumph, and having captured the eye of the American public, he eventually

won a bid for the White House.]

Though the number of Indian

casualties from the Battle of Lake Okeechobee is unknown, and considered

minimal, the effect the battle had on the Indian psyche was devastating.

The majority of them fled to the relative isolation of the Everglades,

and others were captured. The U.S.

government moved many of the imprisoned Seminoles, including Osceola, King

Philip, Micanope, and others, to Fort Moultrie in South Carolina where they

would no longer present an immediate threat or be encouraged to escape.

Further representing the effect this had on the Seminoles, Osceola died

within a month of reaching his new prison in the Carolinas.

King Philip died not long after.

The war managed to drag on for

another four years with constant skirmishes, raids, and sniping from the

Seminoles led by Chief Billy Bowlegs and other remaining chiefs, but the concerted resistance was, for the most part, broken.

Those who did not escape, such as Coacoochee and his tribe, were

relocated to the Indian reservations in the West, and many Negroes were returned

to slavery, though many more were allowed to travel with the Indians as their

“possessions” and relocate with the Seminoles.

In 1842, the U.S. Army finally conceded that the remaining Indians should

be allowed to remain in Florida, and the Second Seminole War was officially

concluded, though attacks on white settlers continued for years, as did the

deportation of Indians to the West. Still, the Seminoles were one of the

only tribes to never officially surrender.

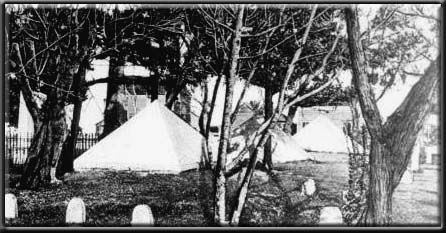

In August 1842, a memorial

service was held to honor the fallen servicemen of the Second Seminole War.

Remains disinterred from random battle sites (i.e. Dade’s Massacre)

across the state were reburied in St. Francis Cemetery [now the St. Augustine

National Cemetery]. Three large

pyramids were erected in monument to those buried in the mass grave.

Second Seminole War Monuments, St. Augustine

National Cemetery.

[Many say the cemetery, St.

Francis Park, and even the nearby St. Francis Inn are haunted.

Now why would dozens of soldiers slaughtered by Indians, dug up, and

reburied under pyramids virtually on top of an ancient Indian burial ground (St.

Francis Park), want to haunt us?

As an added note, after the

death of her father, the daughter of retired British Royal Marine Colonel Thomas

Henry Dummet turned his St. Augustine residence into the St. Francis Inn (which

is directly across the street from the Castillo de San Marcos, a.k.a. Ft.

Marion). This was his second home,

as his primary residence was the enormous plantation he purchased for a bargain

price in 1838, The Dun-Lawton Plantation.

I can’t resist adding that

one of Dummet’s daughters married the famous Confederate General William J. Hardee,

author of the "United States Rifle and Light-Infantry Tactics". The unmarried

daughter, Anna, who founded the inn, was key in erecting the Memorial to the

Honourable Confederate Dead obelisk in St. Augustine. My hometown. What

a small world.]

I wanted to list the names of

my ancestors who fought in the Seminole Wars, but I actually ended up making

this page far longer than I intended. Therefore,

to save space, I am only going to list the names of those in my direct ancestry

who fought and will omit their units for now. Maybe

some day soon, I will add another page to honour those units.

I am also omitting their ranks, as many were privates during one

enlistment, a sergeant or captain the next.

In no particular order (the ones I’m sure of):

John D. Osteen, Fisher Gaskins,

Willis Medlin, Willis Robert Medlin (Jr.), Allen Osteen, Zachariah (Jack) Davis,

and Joseph (Josiah) Parrish, Henry Smith, and Bunyan Mathis.

Others in question (do not have

positive proof yet, but are almost convinced of their participation): William

Riley Hays, Robert R. French, and Benjamin Hale.

Almost all of these men, my direct

ancestors, had numerous brothers and cousins and friends who served right alongside them, and to these

men I offer my thanks for keeping them alive, so I could be here today.

If you have any information to

share on the names listed in my “no positive proof” category, I would love

to add them to my “positive proof” group.

Any other questions, give me a shout, and I’ll see if I can help.

![]()

![]()

©Ty Starkey, April 2003.