|

Mid-Missouri |

|

P.O. Box 268 |

|

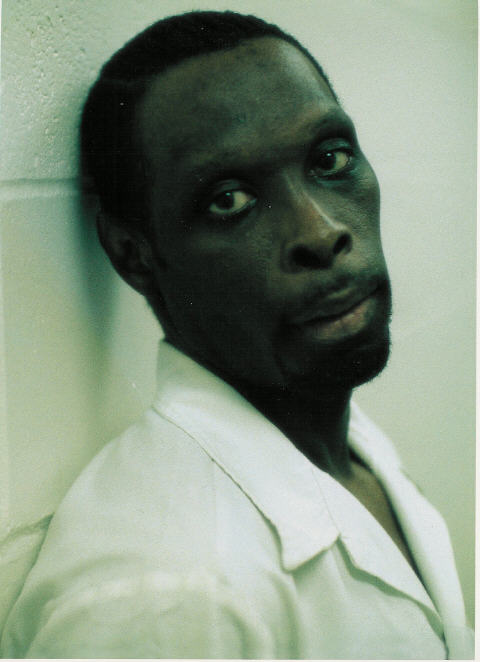

Jerome Mallett indeed did fatally shoot Highway Patrol Trooper James Froemsdorf in March 1985. We of FOR extend condolences to Trooper Froemsdorf’s widow, other family members and friends grieving his death. We condemn both his killing and the execution of Mallett, planned late Tuesday night, just after midnight, July 11, recognizing the latter as a further tragedy which would create yet another set of mourners.

The Crime.

Officer Froemsdorf stopped Mallett as he was speeding on Interstate 55 in Perry County north of Cape Girardeau. Mallett lied to the officer about his name and said he’d lost his wallet. Suspicious, the trooper handcuffed him, searched the car, found his wallet and soon learned Jerome was wanted in Texas on charges of probation violations and robbery. In his last radio transmission, Froemsdorf said he’d be bringing the fugitive to jail. Mallett, after he was apprehended a couple days later following an intensive manhunt, waived his Miranda rights and made a videotaped confession.

Mallett said Freomsdorf lightly struck him, displeased with the lies. Due to an injury he sustained as a youth, Mallett was able to slip his right hand out of the handcuff, something he said enabled him to defensively halt the trooper from hitting him again. Froemsdorf consequently drew his revolver, according to Mallett, who out of fear, said he clutched at the gun.

In the struggle the gun was fired several times, including three bullets, one hitting the trooper in the chest (protected by a bulletproof vest) then fatally twice in the neck. There were no other witnesses. Physical evidence showed there had been a struggle in the car. In a duel of theories, the jury accepted the prosecutor’s version of Mallett’s malicious intent and sentenced him to death. Yet many other issues figured more prominently in determining the outcome.

Racism and Bias

Not surprisingly, with the killing of a trooper, court officials earnestly sought the harshest punishment. Perry County Judge Stanley Murphy did grant the request of Mallett’s defense attorney Kenny Hulshoff to assign the case to another county on a change of venue. Hulshoff (who soon after this case, began working for the Attorney General’s office, securing death sentences against a half dozen defendants before being elected to congress) was concerned the county had too small a minority population to assemble a jury of his peers, racially.

Incredibly, Murphy transferrred the case to Schuyler County. The county borders Iowa, and according to the 1980 census had just three African-Americans among a population of nearly 5000 people. Curiously, the case came before Judge Richard Webber. Hulshoff learned while preparing for trial, Webber had written a eulogy for Froemsdorf, signed it with a pseudonym, and personally presented it on a plaque to the state highway patrol headquarters. Hulshoff urged Webber without success to recuse himself from the case.

Mallett’s appeal for clemency, advanced to Governor Holden’s office on Friday, reports, "Justice must be more than fair. It must also appear to be fair,... Regardless of the transferring judge’s intent, it appears as if he greased the skids for the administration of a death sentence."

The relocation had the same effect essentially as the prosecutorial practice, since ruled unconstitutional, of "striking" all Blacks from a pool of prospective jurors. African-American defendants are twenty times more likely to be sentenced to death in Missouri when no member of their race serves on the jury, according to a 1994 report prepared by UMC Sociology Professor John F. Galliher, and Dr. David Keys for the Missouri Public Defender Commission, They also noted that half of the Black defendants convicted in the state of capital murder in the state were sentenced by juries without Blacks.

The highway patrol also maintained a very high-profile presence in the courtroom, according to the document, as 11 of their 12 top officers attended parts of the trial. Many patrolmen in uniform and some in plainclothes filled the courtroom; some for security, many to show support for the widow of the slain officer. But the large contingent also suggested jurors should return the harshest sentence. Two department planes patrolled the skies over the courthouse throughout the proceedings, further conveying a sense of urgency.

Arbitrary Punishment

Mallett’s clemency application identifies a half dozen Missouri cases in which assailants killed law-enforcement officers yet they received life sentences, even though in most instances greater evidence of pre-meditation was presented. Among them, was David Tate, a White supremacist who after being stopped in 1987 while transporting automatic weapons and grenades in southwest Missouri, killed one highway patrolmen and critically wounded a second, who testified in court.

Evidence of Redemption and Rehabilitation

"Jerome Mallett is not the same individual he was sixteen years ago," contends the clemency application, submitted by his current attorney Michael Gorla and Caryn Tatelli, a forensic social worker. "He has been removed from his reckless, drug-infested lifestyle. He has grown. He has taken responsibility for his own behavior, and the consequences of that behavior."

Jerome has a loving and supportive family: a father, sister, three brothers, a cousin and other relatives who would be devastated by his execution. They note he has often expressed to them his remorse for the shooting. According to his sister-in-law Gayle Mallett, Jerome "is haunted by the knowledge that someone died at his hands."

Pages of accounts from relatives support the assertion that "despite the fact he has been incarcerated since March of 1985, he remains a vital, integral part of this family unit. He has continued to provide guidance and thoughtful wisdom born from one who has recognized the mistakes of his own past." Jerome’s youner brother Patrick, a computer technician and Army Reserve captain, recalls for instance that after separating and divorcing his wife, Jerome was instrumental in helping them work through problems. They remarried two years ago. In recent years, Jerome has served as a role model for Patrick’s five children, making clear the "kinds of problems which can come from poor life choices."

Mallett has served as a father figure to the three children—all girls, now 19, 17 and 13-- of his cousin, Jennifer Jordan. He’s written and called frequently over the past three years, soon after her husband died. Jordan was especially moved by a letter that Jerome wrote to her 17-year old daughter Jennetta on March 21, 2000. "You have a lot of talent . . . I am not able to do anything so I want you to all the things I can’t. Just have fun with your life and make smart decisions. Don’t think the way I used to think. Think as I think now."

Jerome is careful that none of her children feel left out. He recently drew and sent Tanesha, the thirteen year old, a cartoon about school. The cartoon shows her sitting in a classroom with two other students and a teacher. It is titled What do you know? The caption reads, "Nesha, if you had $833.00 and you paid 18.5 percent taxes, what would you have?" The response, "A damn headache!" At the bottom of the cartoon, Jerome wrote, "The more you know, the farther you go."

Gayle and Patrick Mallett recognize their kids’ unruly behavior changes for the better after being summoned to visit Uncle Jerome at Potosi Correctional Center. "Even now that Jerome is facing execution," the clemency application state, "he is still actively working to encourage his nieces and nephews to do postive things with their lives. In fact, he said that if he is executed, he is going to ‘milk it for all it worth’ and extract promises from each of his nieces and nephews that they will go to college. He intends to tell them that college was a dream he never achieved, and to ask them to go to college and excel in his name." His relatives express concern the execution would devastate the whole family, especially the younger relatives and Mallett’s 66-year old father whose wife died several years ago.

The application shows Mallett to be someone who would continue to find meaning in his existence even if having to dwell for all of his natural life in prison. Reports from a half dozen prisoners speak of a positive influence Mallett has made in their lives. Donald L. Williams, one of Jerome’s former cellmates writes, "I was in a gang and he showed me that I could do other things with my life . . . He showed me that I could go to college and make it . . I’m not in a gang no more and I want to fix computers when I get out . . . He help (s) everybody and show us that you can do right and still be cool."

As a final gesture of compassion, Mallett has offered to donate a kidney to a family friend who has been undergoing dialysis treatments since 1996 and is the father of three. A St. Louis hospital has been cautious since they recognize the chance for disease from an incarcerated donor is greater. He’s also agreed to donate any organ if in fact any of them would still be viable after he would be fatally poisoned.