|

Home Page

Discovery of Atlantis

First Empire-(1) to 261

Second Empire- (1) 361 - 409 |

|

The

Descent to Revolution : "Unturgeso Tonnouphar": Meison I and

Crehonerex III, 563 - 585

MEISON I, 563 - 572 : THE ATTEMPT TO SAVE THE EMPIRE Following the death of Thildo, the "Alliance" virtually presented the throne to Meison, who had been sounded out in advance. Meison was the ex-Civilian Governor of Yc´el Atlantis, and was known as a moderate liberal. (He had in fact been dismissed by Thildo in 562, and went into hiding in fear of his life). To be exact, he was in the elite liberal tradition of most of the Emperors of the Second Empire. He wanted to return to the relatively liberal authoritarianism of the earlier Emperors, and he was evidently quite aware that to continue down the path of the harshly authoritarian rule of more recent rulers could well lead to social breakdown. The difficulty was that he could not, because he did not want to, move very far to accommodate the growing radicalism of the populists, who wanted root and branch changes to the whole imperial, political and social system. At the same time, the ruling classes of the Empire had become increasingly hidebound and traditionalist, and would become more and more resentful of almost any changes which Meison might wish to make. Meison made the last, fairly feeble, and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to turn back the Empire from the abyss which yawned in front of it. THE ATTEMPTS AT REFORM Meison was 46 when he came to the throne, and had a standard, quite liberal upbringing, and was now married with three children. Since the 550s he had become increasingly influenced by liberal artists and writers, and as Emperor made sure his advisers and Controllers were as liberally minded as possible. The backers of his coup against Thildo, many of whom were innately conservative, were gradually left out in the cold. Meison began by largely abandoning the Class and honour system set up again by Crehonerex II, and appointed no more Class Is. He re-established good relations with the Council, attended many of their debates, and at least listened to their demands. These demands, much more moderate than those being aired by the populists of the lower classes in the streets, included the abolition of the Class system, Land reform, and more poor relief for the cities. After 568, Meison began increasingly to agree to the Council's demands over appointments, longer sittings, more powers for Civil Governors and the rights of the Province of Atlantis (no Imperial Governor nor conscription). However little attempt was made to heal the growing social divide between the classes, or deal with the increase in poverty and hardship within the Empire. Indeed after 570, Meison unhelpfully decreed an increase in Court ceremonial and formality, something which his successor would continue. THE BARBARIANS PRESS ON THE BORDERS As always, there was intermittent but strong pressure by migrating nomads on the northern borders of the Empire. These barbarians, as the Atlanteans called them, had over the past 30 years forced their way gradually westwards, intruding into Geskeltan´eh and Nunchalcr´eh en route. Geskeltan´eh was by now partly settled by these nomads, and it proved impossible for Atlantis to regain control of it. Recognising the inevitable, Meison finally abandoned it as a Province, evacuating the remaining citizens, and calling it instead a Military Border. The nomads continued to bear down on the Kelts who lived outside the borders of Atlantis, while others raided through Nunchalcr´eh and Nun- keltan´eh. After 570, a second, quite different wave of barbarians, largely on horse, and wielding swords and bows and arrows, rode into the Ughan and Keltish Marches, and then into the former Geskeltan´eh and east Keltish areas. The main result was that they forced many of the first wave of nomads, who had begun to settle in these areas, to flee further west again, through or round to the north of the Kelts, after which they came up against the eastern fringes of Eliossien territory, namely its so-called Protectorate. By 585 they had completely overwhelmed this area, and then threw themselves against Eliossie proper, which they conquered and occupied by 590, after a heroic defence by Eliossien troops. Raids also grew against Atlantis' southern borders (Manralia, and later Thiss Provinces) by the partly civilised tribes and kingdoms of the desert areas. For several decades, Atlantis had encouraged local or "provincial" armies to help defend these southern zones, and throughout this period, these forces did help to protect what was, after all, their own home territory. THE REVENGE OF THE "OLD GUARD" By around 570, Meison appeared to be growing ever more receptive to the demands of the Council for reform, and was even meeting radicals of the lower classes to listen to their almost socialist programmes. In 570, he announced some extremely far-reaching reforms to be carried out over the next two years, including limitations of the ownership of land by the nobility, participation by the Council in all executive appointments. Other goals, too, were proposed, though never explicitly : in later years, it was claimed by the republicans that these anticipated many of the Council's own ideas as set forth in the Accord of 586, at the time of the overthrow of Meison's successor, Crehonerex III. However, Meison had no chance to put any of these ideas into practice, as in March 572, he was found drowned while swimming in Lake Oncia near Cennatlantis. The republicans in later years claimed that Meison was murdered by a group of conservatives, who were aghast at the Emperor's excessively liberal plans for the Empire, and who were especially frightened that he would divest them of all power in the future. There is certainly good cause for suspicion, and the consensus nowadays amongst historians of Atlantis is that Meison was indeed murdered. For one thing, of course, the next Emperor did indeed prove far more sympathetic to the conservative cause. Secondly, Meison's death by drowning is itself extremely odd, as he was a good swimmer and the lake was placid. Furthermore, he was normally always within sight of guards when he went swimming, but on this occasion he was said to have swum off on his own and disappeared. In fact his movements for over three hours are unaccounted for, as is the fact that his five personal guards ( all good swimmers) were not with him. It was claimed that this was at his own request, and yet all these guards met strange fates. One literally vanished, and another conveniently committed suicide ( drowning himself in the same part of the lake where the Emperor had met his fate.) A third guard admitted negligence at the ensuing trial, and yet was let off with a very light sentence. The other two guards gave no convincing explanation for their movements on the fatal day at all. Meison's family were at first suspicious, but seem to have been silenced by Meison's own very generous will and by a government donation. One son who persisted in protesting was imprisoned by Crehonerex III for "lese-majeste", and later died in prison. Meison had never really decided on his successor. Initially he had favoured either his elder son, or his nephew, Crehonerex, who he believed held fairly liberal views on running the Empire. Later he came to believe he should not favour a member of his own family, but he never settled on any particular person. On Meison's death. Crehonerex, supported by a group of conservatively minded Councillors and the Governor of Chalcr´eh, one of Meison's greatest enemies, proclaimed his own succession to the throne, as being in accordance with Meison's original wish. There was no effective opposition, least of all from Meison's son, who conveniently expressed no personal interest at all. Crehonerex proved in fact to be a real conservative, as his supporters knew, though Meison, earlier, was probably taken in by his flirtations with liberal ideas as a young man. Meison probably realised his mistake later on, which was why he seemed to back away from supporting him as a successor.

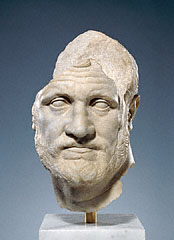

A head of the Emperor Meison I, sculpted in a

very

CREHONEREX III, 572 - 585 : THE BREAK-UP OF THE SECOND EMPIRE

Bust of Crehonerex III A LIBERAL HEART BUT A CONSERVATIVE HEAD Crehonerex III was precisely the wrong man at the wrong time as far as the survival of the Second Empire was concerned. In character he was a weak, impressionable man, who, like many such people, could also at times be disastrously stubborn. It has been said that while his head was somewhat liberal, his heart was conservative. Certainly in his youth in the 540s he had indulged in poetry and light prose, and turned put a number of moderately outspoken and liberal pieces which made him for a while the darling of the liberal artists. This was at a time when the prevailing ethos of the government , under Crehonerex II, was becoming increasingly harsh and reactionary. But this liberalism, like that of many of the upper-class liberal artists of the time, was more of an escape from the real world than any genuine or heart-felt political commitment to social change. Art, by the time of the mid sixth century, had become split, like society, into at least three very different movements. Firstly, the Romantic movement, whose greatest exponent up to the 550s in music and drama had been Thoulpas, became more and more removed from the everyday world. Poetry, music, drama, and the Total Work of Art were cultivated purely for the expression of the artist's own, subjective feelings, and such works became unintelligible to the majority of laymen. The most extreme proponents of this movement, elitist and esoteric, became known as hermeticists. One of the best-known hermetic poets was Buomusse (552-589); and Giestizzi( 543-608) was an important hermetic composer. Many people could not follow this path, including the increasingly conservative establishment, and they looked to an art which reflected the more easily understood early Romanticism of the 480-530 period. Finally, there was a completely new, radical, lower-class art , which rejected all these things as elitist, and instead fostered art as entertainment for the masses - popular songs and music, broad farces, and, increasingly, satire of the establishment. This art of the people, a true art of protest, was to form the background to popular discontent with the Imperial regime, and would in time be the only art-form to survive into the revolutionary and republican period of the late 580s and 590s. Crehonerex himself thus flirted with the forward edge of high class liberal art, which had no connection at all with the arts of the lower classes. In any case, he soon hid this side of himself, and worked his way up the usual channels to become a Councillor in 555, acting and sounding most of the time much like any other of the now conservative ruling classes. When Thildo seized power, Crehonerex seems to have gone into hiding as a country gentlemen , but evidently played some part in the conspiracy to bring down Thildo on 563. With Meison I's succession, his career resumed and he became an Advisor to his uncle in 569. He seems to have been somewhat two-faced with his opinions, showing his conservative side privately, but maintaining a sort of liberalism in his dealings with the Emperor. He had married in 560, and by 572, at the age of 46, had five children. When he became emperor himself, he seemed at times to be almost schizophrenic in the way he displayed different, often contradictory aspects of his personality. He swayed between conciliation and despotism, authority and submissiveness to other peoples' views, between excessive reverence for all that was old and traditional in Atlantis and a desire to make some small compromises to suit the changing present. In the end, a rising tide of troubles - social and political unrest, food shortages, ethnic disturbances, religious quarrels, and finally military breakdown and rebellion in the Basquec War - forced him to clamp down with increasing brutality all the time: but this in itself simply led all the more surely to the final explosion, collapse and revolution. THE GROWTH OF UNREST AND MISGOVERNMENT It did not take Crehonerex III long after 572 to surround himself with many of the same Class 1 conservatives brought to power 20 years earlier by Crehonerex II. Class honours were reintroduced in 573, while Meison I's concessions to the Council were gradually repealed. Crehonerex took little care over the character of the Military Governors he appointed, and, with no firm restraining hand from the top, these became increasingly corrupt, rapacious and independent of Imperial control, much to the anger of their subjects. Unrest in the Provinces became endemic in some areas, and more and more Provinces were militarised - Marossan in 576, Razira (a new Province) in 577, and Helvr´eh in 578. Atlantis (Prov) was also upset by proposals to introduce conscription in it for the first time, and appoint a relation of the Emperor as its Governor. Conflict also grew with the Council, and after 576 Crehonerex said that it would not be opened in the spring in future. It began independent sittings in 578, and in 580 over half the Councillors rebelled against the Emperor's pronouncements and moved themselves permanently to Atlantis for the whole year. (This was at a time when the Emperor and his court now spent 9 months of each year in Cennatlantis.) Crehonerex immediately dissolved this illegal Council, using force. In 581 the rebels declared their Council constitutionally part of the Atlantean Provincial Council, and this could not, at this stage, be separately dissolved. In fact it was simply ignored by the Government in future. From now on, the special treatment that Atlantis Province had by hallowed tradition always been accorded by the Government ceased. In 578 Crehonerex increased the "Bodyguard" Army - a small force which Emperors had always kept in Atlantis for personal protection. In 579 he introduced conscription in Atlantis, to howls of outrage. Soon after there took place an Atlantean attempted to kill Crehonerex in Chalcr´eh, the second such assassination attempt in two years. Immediately after, police activity (now centralised again) in Atlantis was greatly increased, and the links between police, Class 1 and 2 conservative landowners and the Government against provincial, lower class and radical agitators grew ever closer. Demands for reform of the government became louder and louder as the 580s dawned, and more and more people decided that they would not stand any longer for the growing gap between well-off upper classes and poor lower ones. Food shortages, bad harvests, the effects of inflation, misgovernment at central and provincial level, as well as the ambition of some Councillors and other agitators began to push the whole Empire to a crisis point. Added to this was the influence of the new popular religions and the propaganda of the populist mass art of the period, along with the hatred of the big Class 1 and 2 landowners in Atlantis and Atlantid´eh by the poorer classes. Meanwhile upheavals and troubles continued. In 581, two Military Governors issued a statement of support for the new Council, now in Atlantis, while in Helvr´eh loyal army units crushed radical civilian protests and the Civil Governor was arrested and executed. Finally in December, Crehonerex's nephew, the new Governor of Atlantis (Prov) was murdered. THE BASQUEC WAR AND THE REBELLION OF THE COUNCIL In 581 Crehonerex and a small circle of his closest cronies made a fateful decision, one which more than any other brought about their own downfalls. In some ways Crehonerex was genuinely bewildered and upset by the growing opposition both toward him and his whole governing circle. He could not possibly backtrack on his policies now - apart from anything else he was overawed by his stronger conservative advisers, who saw any concessions as threats to themselves, their way of life and their power in running the Empire. So he decided to start a war, which, after a few successes, he hoped would reunite the Empire behind him, and divert attention from social problems at home. Following some specious objections by the Atlanteans about Basquec provocations and incursions on the mutual border, Atlantis declared war on the Basquecs. (At this period, the Basquecs were ruled by the Emperor (Zuigo) Tovplich.) As far as possible, army units from the east of the Empire were used to avoid committing potentially disloyal western ones. But the impact of the war soon impinged on the western Provinces, especially Atlantis, and anti-conscription riots swept through the towns. Large landowners in Atlantis and Atlantid´eh also began to suffer attacks on their property and on their families. The Atlantean provincial and the "illegal rebel" Councils swore indissoluble links with the Helvran and Atlantid Provincial Councils. As a result, a new, tough Governor was imposed on Atlantis. Meanwhile the war with the Basquecs ("Crehei ante Basquecix") quickly bogged down into a costly stalemate. The Atlantean army came up against numerous, strong Basquec fortresses on the border, which it was quite unable to take. The Basquecs aimed to avoid open battles, and shelter within their fortifications, but even when rare battles in the field did take place, the Atlanteans found that their enemies were usually more than a match for them. Gradually the morale of the Atlantean troops fell, and soon there was increasing dissent and division amongst the army units from the various parts of the Empire. These rebellious feelings extended all over the Empire, and not just on the Basquec front-line. Thus the units raised from the Province of Atlantis, and stationed in Marossan and Naokeltan´eh were greatly influenced by the feelings of the citizens and councillors in their home province, as were the militias which had been reluctantly raised by the Imperial Government. Equally the auxiliaries in Th. Thiss and Manralia became openly rebellious due to the oppression of the Governors and the Imperial Army in those Provinces. In 583 all the Provinces of the Empire were militarised, but this met strong protests, especially from the Civil Governors of Yc´el Atlantis, Atlantid´eh and Nundatlantid´eh. In 584, the armies recruited from the Province of Atlantis refused to march to the Basquec front, and they were supported by the Council of Atlantis, as well as the Governors, Civil and Military, of Marossan, Yc´el Atlantis, the Atlantid´ehs and the Civil governor of Th. Thiss. Some of this support was due to fear, but some also due to a desire to pre-empt more extreme elements from seizing power, by overthrowing Crehonerex and replacing him with a more moderate successor. The Council also produced a Charter of its demands for change, and the hard-line Governor of Atlantis was hounded out of the Province, narrowly escaping with his life. THE OVERTHROW OF CREHONEREX Events now gained a momentum of their own. There were further defeats and heavy loss of life at the war front, and the Emperor was forced to raise more armies from auxiliaries, local militias and recently conscripted troops. Then in 585 the Helvran-raised Armies in Basquec´eh mutinied, as did the newly-raised Manralian Army. Just prior to this, Crehonerex had ordered the "loyal" Armies in Borchalcr´eh to march into Atlantis Province, occupy the capital, and arrest the rebel ringleaders. When this took place, they were confronted by rebellious militia and the arrival of the three Atlantean Armies from Marossan and Naokeltan´eh. After a small skirmish, two of the loyal Armies, in the presence of the Emperor, retired temporarily. Now a real civil war loomed, and some Governors ordered the Armies of their Provinces home to maintain order. The Emperor himself with some loyal troops returned to Cennatlantis and decreed the abolition of all councils and the replacement of several Governors and other military leaders. At the same time he told the completely loyal Armies in Dravid´eh to march westwards for a new and stronger offensive against the rebels. But as these troops marched back through Chalcr´eh, their lawless behaviour led to serious complaints, and actions by the civilians en route, and then a revolt by the Governor of Chalcr´eh I. There followed a brief civil war, during which the armies in Basquec´eh remained quiescent and largely neutral, except for the Helvrans and Manralians. The Emperor, with a hastily convened force, marched into Atlantid´eh. Using all possible means, including the signal telegraph, the Atlantean leaders got together as many rebels from Atlantis and the more northern Provinces as possible, and using small bodies of troops, they more or less surrounded the slow and cumbersome Imperial army, and forced it to retreat at the Battle of Tilrase. Other rebel Helvran and Manralian troops returning westwards from the war front were intercepted as they marched through Meistay´eh by loyal Dravidean forces and compelled to retreat into Helvr´eh. At this point, many of the Imperial Advisors and loyalist Governors, believing they were standing on the edge of the abyss, would have no more confrontation. When Crehonerex refused to back down or compromise with the rebels, they forced him to resign, in favour of one of his nephews, Meison, a noted and genuine liberal.

4. Revolution and the Triumph of the Republicans, 585 - 591. "SAISSO SIL ATLANTISAN" ("THE ATLANTIS ACCORD") OF 586 The new Emperor was a liberal-minded man, who was prepared to go to almost any lengths to hold the Empire together. In his early days he had been an admirer of the great Atlanicerex dynasty of the previous century, but he was intelligent enough to understand that the clock could not be turned back, and that the Empire must reform itself root and branch if it was to survive the internal turmoil that now threatened it. He quickly surrounded himself with like-minded Advisors and Governors, and sacked or banished all the adherents of the previous regime. Crehonerex III was sent to live on an estate he possessed in Yall. Thiss., and forbidden to move outside it or make any political pronouncements on pain of imprisonment. This gentle treatment of Crehonerex was the first of Meison's mistakes. Crehonerex's estate became the meeting-place for conservatives who hated Meison's conciliatory treatment of the Council and the other rebels. He was also not far from the main army on the Basquec front, which, as the Basquec War was ended the following year, represented a potential striking-force for anyone wishing to overthrow Meison and the liberals. In particular, the commander-in-chief of the armies fighting the Basquecs, General Lingon, did not hide his contempt for the failure of Meison to use military might to crush the Council in Atlantis.Meison now set out to find a compromise with the Council. He asked the leading reformers of the Council to set down their demands on the running of the Empire. This they quickly did, and within a few months of intensive negotiation, Meison agreed to implement nearly all their demands. This agreement was known as the "Atlantis Accord" of 586. The basic provisions were as follows : 1. The Council has an inalienable right to meet, and may never be dissolved by the Emperor. It will sit in Atlantis for 6 months in a year. 2. There should be much greater equality of opportunity for all within local government. 3. Peace must be made with Basquec´eh, the army reduced in size, and moved to the borders, and especially out of Atlantis Province. 4. Militias, under Provincial control, should take the place of the army for internal security. 5. The Inner Council must again be involved in decisions to appoint new Governors, Controllers and Advisors. (The council originally wanted a complete veto on such appointments). 6. The re-establishment of Provincial control of education, transport, trade and Atlantean affairs. 7. The dismissal of all Controllers and Governors who had supported the military suppression of the Council. (The council originally wanted this to include most of the officers on the Basquec front). 8. Limitations to be set on the size of estates owned by nobles. 9. The abolition of Classes 1 and 2. (The Council originally wanted the whole class system abolished). 10. All honorary posts in the Council are to be gradually abolished. (Compromise period was over 4 years). At this stage, the leaders of the Council, led by Fembel, and also including Tuaingeyu and Lingon, were themselves fairly moderate, as can be seen by their demands. They represented Class 3s and upper 4s, small landowners, merchants and lawyers, with some financial means of their own. They were the agitators of the 570s and early 580s, and so often in their forties or fifties. They were mostly concerned to establish their own positions, and the legitimacy of the Council's role. They did not look too far into the future, and certainly had no intention of overthrowing the institution of monarchy as such, or of forcing their views on the whole Empire by military conquest. They were opposed by another much more radical party in the Council, and outside it, of a younger generation. These people were usually strongly religious, albeit in the manner of the popular religions of the period, not the official Atlantean faith of the establishment. They came from the lower Class 4s, from families of small family businesses or from trade. They were much more passionate about their beliefs than their older colleagues, and were usually strongly republican and anti-Imperialist, and espoused radical ideas - decentralisation, democracy, equality of rights and opportunity for all, justice for all, an independent and all-powerful legal system, and peace abroad. "Ruthouso til dimebayun erneathe ruthouso til tontayun." (Pranonni, 587) "The happiness of the few will become the happiness of all." THE OVERTHROW OF MEISON AND THE RENEWAL OF THE CIVIL WAR As soon as Meison started to put the provisions of this Accord into effect, his opponents in Cennatlantis and in the army began to criticise him more and more fiercely. In the latter part of 586 and the beginning of 587, the Council took up its old right of regular sittings, and various Provinces were demilitarised. Meison began negotiations to end the Basquec War, and peace was made by the end of 586. Those Armies which came originally from the western rebellious Provinces were the first to take themselves off home. As these units consisted of five Armies of troops raised from Helvr´eh, and one from Manralia, they would clearly form a very substantial addition to the troops supporting the Council, should war with the Emperor break out again. Conservatives around the Emperor were indeed horrified at this, as well as the other concessions which Meison was granting to the Council almost week by week. The final straw came in March 587, when Meison began dismissing Governors who had supported a hard-line against the rebels in Crehonerex's time. At the same time armed mobs began to attack or sequester some of the lands of the rich Class 1 and 2 nobles in Atlantis and Atlantid´eh, as they claimed was permitted according to the 586 Accord on land reform. Meison's opponents now struck. Eight Armies, (about 85000 men) originally from Dravid´eh, Chalcr´eh and Razira, were to return to their home Provinces, now the Basquec War was over. They were fiercely loyal to their commander-in-chief, General Lingon, and he was determined to overthrow Meison and crush the rebels. Crehonerex, who had been banished by Meison to Yall Thiss, nearby, was immediately hailed as the new, or rather restored, Emperor, and the whole force veered towards Cennatlantis. Meison and his circle had virtually no friendly army to defend them, and apart from one or two officials who managed to escape westwards to Atlantis, all were captured by Crehonerex and Lingon. Crehonerex was once again made Emperor, all the old hard-line cronies returned, but this time the steely Lingon and his army were right behind the Emperor and his supporters, and future policy towards the Council was far more aggressive than before. It is now impossible to tell how far the tragic developments of the next few years were approved by Crehonerex, as it is clear that he had become little more than a rubber-stamp for the ambitions of Lingon and his Army. For nearly a year there was increasing verbal vituperation between Cennatlantis and Atlantis. The Court stayed permanently in Cennatlantis now, and the Council sat in Atlantis, surrounded by an ever-growing Army of professional troops and militia from Atlantis, Helvr´eh and Marossan. The Council demanded the return of Meison, and when his death was announced, conveniently, another similarly-minded Emperor. Crehonerex ordered the Council to stop building up its armed forces, to move itself to Cennatlantis for its sittings, and to allow three Armies from Cennatlantis to move into Atlantid´eh and Atlantis unopposed. Border skirmishes began to proliferate, and then suddenly in February 588, without warning, Atlantean troops made an all-out dash over the border to seize Cennatlantis and Crehonerex, if possible. They reached and surrounded the city, but were then badly defeated by Lingon and his armies at the second battle of Cennatlantis.

Crehonerex II : his capture and death : 588-591 THE BATTLE OF FOURTIS AND THE CAPTURE OF CREHONEREX Both sides now prepared for the civil war. Crehonerex was able to draw support and troops from Razira, Yall Thiss, Meistay´eh, Dravid´eh I and II, Chalcr´eh I and Vulcan´eh. The Council was fully supported by Atlantis, Yc´el Atlantis, Marossan, Th. Thiss, Manralia, Helvr´eh, Nundatlantid´eh and western Atlantid´eh. The remaining Provinces remained nervously neutral, or in the case of eastern Atlantid´eh, pro-Council but under Imperial occupation. In the summer of 588, seven Imperialist Armies (57000 men), led by General Lingon and accompanied by Crehonerex and much of his Court, moved slowly and cautiously westwards through Atlantid´eh, across the border of Atlantis at the river Bore, and on towards the town of Fourtis, about 65 miles east of Atlantis city. All this time the Atlantean rebels had fallen back steadily, though skirmishing constantly and wearing down the enemy. But as the enemy advanced ever deeper into Atlantis, the simmering rivalry between the more moderate Councilmen like Fembel, Tuaingeyu and Lingon on the one hand, and the more radical republicans such as Pranonni and Soucon came to a head. All-out conscription, fast mobilisation of all troops, and the declaration of a republic were demanded by the young radicals. Soucon devoted himself to the necessary military preparations, while Pranonni called for the resignation of Fembel and his party. In May, after undignified scuffles in the Council chamber, Fembel and the moderates were forced to resign, and Pranonni took over as Council Leader. By July, the Council's troops were as ready as they could be to face Crehonerex's army. Their plan was to meet the enemy in a good defensive position, and then attack them, using small units, able to travel quickly round flanks and into the rear of an enemy. Up to a sixth of their forces were skirmishers, and all the infantry would attack in open lines and a loose formation. This sort of organisation would suit these partly trained but immensely enthusiastic forces, and should be difficult for the slow, heavily armed and cautious Imperialists to deal with. Thus it was that at the battle of Fourtis, on July 4th 588, the rebels confronted the enemy as they approached a line of hills to the west of Fourtis. The rebels attacked the Imperialists' left flank from behind a marshy stream, while on their right other rebel troops successfully defended some woods against all attacks. Meanwhile other rebels circles right round this flank and entered Fourtis behind the imperialists. The latter, having made no progress in their attacks, and now cut off in their rear, finally retreated. Crehonerex and some of his Court, were caught up in a traffic jam as they retired through Fourtis, became separated from their bodyguards, and found themselves surrounded and then captured by the rebels in the town. The rest of the Imperialist force retired around Fourtis, including Lingon, who claimed he did not know until too late of the capture of the Emperor. Others claimed he did not try too hard to rescue him, as he himself wanted to seize the crown. The Imperialists lost 7500 casualties and 12000 prisoners. The rebels, about 47000 strong to begin with, lost 4100 men.

THE FALL OF CENNATLANTIS The more moderate members of the Council tried now to persuade the captive Crehonerex to end the war and accede to their demands. Crehonerex, who at this stage was treated very well, still had high hopes of rescue, despite the defeat of his army at Fourtis. He therefore haughtily refused even to speak to the representatives of the Council unless they released him to return to Cennatlantis. Then the Council's leaders would have to come to him to beg terms. Pranonni, as Leader of the Council, of course refused, and on August 7th declared Crehonerex dethroned. Crehonerex was imprisoned in a small part of one of his own palaces outside Atlantis city, and was kept in some comfort still, because Pranonni hoped he might still be useful as a bargaining point with the Imperial government in Cennatlantis. At the end of the year, the rebels advanced their armies eastwards. They moved fairly deliberately, taking time en route to eject all the noble owners from their country houses or palaces. The buildings were at first often looted and set on fire by the army, and by the increasing number of Atlanteans who followed the army and were anxious to show their support for the Republicans - and their desire for turning the tables on their former masters. Many of these nobles and their families were killed or badly mistreated if they were not able to escape east in time. In due course the Council imposed a bit more discipline on its motley supporters, and in future many nobles were sent as prisoners back to Atlantis, where they were imprisoned, often near to Crehonerex in the old palaces. They were pulled out from time to time and made to march in humiliating processions, along with other prisoners of war, through the centre of Atlantis whenever the Council wanted to celebrate another victory. By July of 589 the Imperialist forces had been pushed right back to Cennatlantis. Pranonni expected to capture the city within the next few weeks, and wanted to use the occasion to declare the Empire a republic ("Saindatea"), which would then be given a completely new constitution. This led to bitter arguments in the Council between moderates, who wanted to elect another Emperor, and the republicans, led by Pranonni, who wanted to make a clean break with the past. But the radicals were very much in control now, and a republic was declared on July 16th 589. At the same time, Atlantis city was declared the capital of the Republic (Empire no longer). Cennatlantis, however, had not fallen, but was under partial siege by the Republicans. The Imperialists, under the energetic Lingon, who now called himself "Imperial Governor", had steadied his armies, whose morale had been close to collapse after the defeats of the previous year. It was not until the October that the Republicans were finally able to cross the river Dodolla, thanks to the desertion of some Imperialist troops. Cennatlantis was now properly surrounded and besieged. Lingon, from the east of the river, made a number of serious attempts to relieve the city, and military details of the four attempts to relieve it by the Imperialists can be found here: The siege of Cennatlantis, part 1 The Siege of Cennatlantis, part 2 The Siege of Cennatlantis, part 3 The siege of Cennatlantis, part 4 The city finally surrendered to the Republicans after a couple of abortive breakout attempts, in January 591. Thereafter, continuing to use their successful tactics of skirmishing, use of loose formations and camouflage, speed of movement, and living off the land, the Republicans advanced on eastwards, overrunning all of Chalcr´eh I in 591 and 592. Their enthusiasm and Úlan overwhelmed the Imperialists, but it must also be remembered that the near-despotic republican government was sending spies to check the loyalty and efficiency of all fighting units, especially the generals. Any failure meant dismissal, and after 590, usually execution. During this period, and afterwards, the whole of the Atlantean Empire, was gradually dividing into two camps, Imperialists and Republicans. The Republicans held the Provinces of Atlantis, Marossan, Yc´el Atlantis, Atlantid´eh, Nundatlantid´eh, the South Island, Th. Thiss. (except for the far south), Helvr´eh, Manralia, Naokeltan´eh and over the next two years, those parts of Chalcr´eh which its armies conquered. On the other side were most of Chalcr´eh I, Chalcr´eh II, Dravid´eh I and II, Meistay´eh, Yall. Thiss., Razira, Vulcan´eh, and Phonerianix. The remaining Provinces remained warily neutral. In 590-591, Crehonerex was tried and executed by the Republicans. For a contemporary account, click Execution of Crehonerex To read about the period of the Republicans and Imperialists, click on Republicans and Imperialists- (1) 591 - 600 |