|

Home Page

Discovery of Atlantis

First Empire-(1) to 261

Second Empire- (1) 361 - 409 |

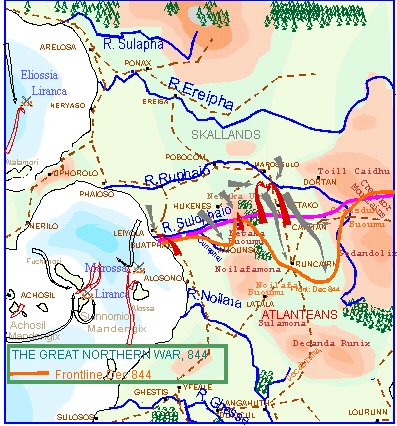

THE GREAT NORTHERN WAR: "BOUR CREHE NUNDAR": 844 - 847 A NEW SORT OF WAR The war that was about to be fought was very different to any preceding war in terms of weapons used and hence the style and scale of the fighting. The last war fought in this area, between the same combatants, had been the great Continental War from 744 to 750. Since then, changes in arms had been huge: all infantry had bolt-action, repeating rifles, capable of many shots per minute, and sighted to over 1000 yards. Machine-guns and entrenchments soon became ubiquitous, while cavalry was almost unused. Artillery, rifled and breech-loading, was much more powerful than in the earlier war, hence the use by infantry of trenches whenever possible. The results of these changes were to make attacks almost suicidal, and forced infantry to dig in to the ground. Increased firepower meant fronts grew much longer, and could be held by fewer men. Much of this is familiar to us from the period leading up to the First World War in 1914 AD. Indeed the beginnings of it had been felt in the middle and later years of the Continental War, especially in the siege of Atlantis from 744-745, and again in some of the sieges of the war against Rabarrieh after 806. But as with the 1914-1918 War, the extension of fronts meant that the whole land frontier between the two combatants became an entrenched battleground, and flanks barely existed. However a number of factors mitigated this stalemate, and meant that armies could still move, albeit more slowly deliberately than in any preceding war. Firstly, both sides had an open flank to the sea. Here again warfare had changed drastically, and the tentative experiments with ironclad steamships of the Continental War had developed into navies of mighty armoured ships with massive guns, capable of firing over 10 miles. Minefield too were spread liberally around ports and harbour installations. Nevertheless, the open sea made it impossible for fronts to solidify as on land, and naval battles and amphibious landings could have great effects on warfare on the land. Secondly, the shape of the main area of conflict on land – the couple of hundred miles between the sea eastwards up the Sulophaio through the Netaka Mountains to the Cresskor mountains -, meant that while the fronts across the Sulophaio and on the mountain ranges were secure and largely unbreachable, both sides could and did force offensives north and south between the two mountain ranges. These might extend north to the Ruphaio or south to or round the Decanda Runix. In particular advances were made up and down the great road running across the Decabrumu north to Runcairn, Anetako and up to Marossulo on the Ruphaio. And whenever either side advanced too far north or south, it laid its over-extended and unentrenched flanks open to counter-attacks from the enemy, from the east round the Netaka Mountains, or further south, from one of the mountain passes like the Netaka Buoumu, the Noilafa Buoumu, the Decabrumu or the Cressdun Buoumu, or from the Taigeheill wood or across the upper part of the Ruphaio round the Decanda Runix. However, the offensives north and south between Ruphaio and Decanda Runix, as well as some of the flanking counter-attacks, were even so only made feasible by the use of another great innovation of this war - tanks. Some steam-driven tanks had of course been used before, in the fighting against Rabarrieh, particularly in the time of the Tyrants. But by 844, the quality and quantity of tanks available to both sides had improved dramatically, and both sides saw them as a war-winning weapon. However, although they could break through stalemated fronts, given some surprise, or hit moving troops in flank, they were still vulnerable to counter-attack and breakdown – hence attacks they spearheaded usually collapsed after a certain initial success. Fighting and breakdowns quickly led to extreme attrition of tanks, and necessitated long interludes while one or both sides rebuilt or repaired its tank-force, prior to another attempted offensive. During the war, both sides mobilised armies on the fighting front, which were unprecedented even in the Continental War of 743-750. By 846, Skallandieh had 1,300,000 man in arms, while Atlantis had 1,600,000 overall. On the actual fighting front on land in 849, Skallandieh concentrated 800000, while Atlantis had 900000, including immediate reserves. Both sides had to introduce conscription, and deaths were enormous – for Skallandieh 350000, and for Atlantis, 380000. Overall casualties approached 700000 for Skallandieh, and 820000 for Atlantis.

844: THE BATTLES OF ANETAKO AND GENNOUTH – ATLANTIS IS DEFEATED IN A NEW TYPE OF WAR Atlantis attacked the Skallands without warning in June, crossing the Sulophaio and investing the capital Leiyola, and trying to secure the Netaka mountain range. At sea, the navy from Sulosos defeated the Skallands near Leiyola and landed troops to seize the disputed island of Alossa by the coast. Atlantis then unleashed its tanks inland, which stormed up the Anetako road on a widening front, beat the Skalland at the First Battle of Anetako, and had soon reached the Ruphaio along at least 30 miles. By July, it looked as if the war would soon be over. But then everything went wrong for the Atlanteans. On land, their forces were unable to take or even entirely besiege Leiyola, while Skalland forces refused to be driven off Netaka mountain. Then the main Skalland tank force emerged from west of the Netaka and across the Ruphaio, and smashed into the Atlantean tanks and the infantry behind them. This Second Battle of Anetako saw the wholesale defeat of the Atlanteans here, and their retreat right back to south of Runcairn, chased by the Skalland tanks. Another Skalland offensive crossed the Sulophaio and reached Amounso in a large salient. Finally by the winter, the whole front solidified as both sides dug in, and the Skallands found their tanks, reduced by casualties and breakdowns, could progress no further. Meanwhile at sea, the Atlanteans suffered other disasters. The Atlantean Achosil navy moved out north up the Phonerianix Lirilix. Its aim was to find and defeat the Skalland navy from Arelosa, but the latter cleverly retired west behind the headland of Phonaria north of Gennouth. It then sprang out at the surprised Atlanteans, and utterly defeated them at the Battle of Gennouth in July. It chased the Atlanteans south, and bombarded the Atlantean naval base at Phonero. It then moved south round the Achosil Mandengix. Some ships remained to face off the remains of the Atlantean fleet lurking there behind the islands and minefields; the rest moved east to find the Sulosos fleet near Leiyola. The Skalland Leiyola fleet was ordered to join the main force behind the western Suinnomiori islands. There it outmanoeuvered and beat the Atlantean navy, as it approached from Leiyola, at the Battle of the Suinnomiori islands. This Atlantean navy now retired back to the Nundler islands, thereby ending naval events for this year. To read the next part of this history, click on (4) 845 |