|

Home Page

Discovery of Atlantis

First Empire-(1) to 261

Second Empire- (1) 361 - 409 |

| Crisis

for Atlantis – her enemies close in for the kill, 745

ATLANTIS BEGINS THE OVERHAUL OF ITS MILITARY ORGANISATION AND STRATEGY It was not until the First Battle of Vailat, and the advance of the Basquecs into Nunhelvengieh, that Atlantis really understood that she faced a crisis greater than any other in her history, certainly since the Revolutionary Wars of the 600s, and possibly even since the Helvran Wars of the Third Century. The main concern of Brancerix, the Imperial Generalissimo, and the other Imperial Officers of State who ran the Empire and the Army, was to sort out the Army. As early as January 744, all Internal Security Armed Forces were amalgamated into the main Armies, while the rearming of all forces with breech-loading rifled weapons to match the Basquecs went on more and more rapidly. Uniforms were also changed over the next year or so: the "picturesque" style of the Third Empire, with breeches, long socks, boots, large hat and elaborate coat, was abolished. In its place, the new rifle-armed infantry wore a close leather hat, a tighter-fitting jacket with fewer decorations, and trousers and socks or gaiters. As casualties mounted, and Gosscalt advanced to the Crolden Hills, the Atlantean regime realised that it needed to create massive reinforcements for the fronts, and limited conscription was now introduced. After the entry of Skallandieh into the war, conscription was extended.

Atlantean soldier, c746

By 745, there were about 40 Armies in the field, each in theory about 23000 men strong, with up to 150000 inland, garrisoning fortresses, or being trained. These PUEGGISIX were now grouped into BORPUEGGISIX (Grand Armies) of from 3 to 7 Armies each. One of more of these BORPUEGGISIX defended the various fronts, on which Atlantis faced her enemies. These Fronts became "official" after 745, and each had its own Commander, or Grand General. The Fronts in 745-5 were Central (around Cennatlantis and north), Nunhelvengieh, Manralia, Siphiya and the extreme south, and Anauren (the front opposite Skallandieh). Some changing of generals had begun in 744, but thereafter the successive Atlantean disasters led Brancerix to a much greater overhaul of his whole administration. At the start of 745, the commander of the Central Front, as it became, was dismissed and replaced by General Buentel, who had impressed Brancerix by his tenacious defence in the battle of Dravizzi. The northern front, against Skallandieh, was handed to General Elthul in 746, to try to retrieve the situation there. But the war was producing other, larger-scale social changes in Atlantis as well. Conscription and larger armies increased social mobility and a desire for change from the moribund and rigid Third Empire structure, with all power still being in the hands of the Squires. Factories had to be built, and production increased to meet the demands for new weapons, and this strengthened the status and power of middle-class businessmen and factory-owners. The military disasters of 743-746 led to a realisation by everyone that the current military structure and personnel were ossified. Brancerix, to give him credit, soon realised this, and gradually made changes, which brought non-noble but efficient commanders to the fore, purely as a result of merit, not birth. Such men, who also entered some parts of government in the crisis of the times, would not willingly want to relinquish power again, after the war was over. And what of the Emperor himself? It has to be said that he rose to the occasion. He knew his limitations, and made no attempt to lead his armies, or pretend to be a great general, like Gosscalt on the other side. Rather, he made himself a facilitator, the person who organised the whole Atlantean war-effort at the administrative level, sacking and appointing men as needed, and making sure supplies reached the fronts, and, above all, that Atlantis never admitted any possibility of defeat, even in the darkest hours of 745 and 746. DISASTER IN THE EAST – THE ATLANTEANS ARE FORCED BACK TO CENNATLANTIS Gosscalt spent the winter of 744-5 refining the next stage of his attack against the Atlanteans from the Crolden Hills. His great objective was the capital, Cennatlantis. He was certain that if he could once take that city, Brancerix would at the very least consent to negotiations towards peace, and would perforce have to hand over large tracts of territory. The Basquecs now had about 230000 men facing the Atlanteans north of the Gestes, while the Ughans had 170000, that is 400000 altogether. This far outnumbered the Atlanteans, who had about 310000 facing their enemies in these areas. Gosscalt planned a double-pronged attack against Cennatlantis: the northern prong would cross the river Burastoura, while the southern approached south of Lake Trannolla. This force would also try to find the chance to advance on to Helvris, which lay only 70 miles or so further west. The northern army also contained a token force of 18000 Ughans, though for Gosscalt, the main function of the Ughans would be to protect his northern flank. The chief problem was how to deal with the Atlantean army at present sitting at Yellis. Gosscalt decided on a feint against Yellis with 20000 men, while the main army, of 120000 men, crossed the Burastoura some 20 miles to the north, hit the Atlanteans in flank, brushing them southwards, while most of the Basquecs stormed on south down the main road to Cennatlantis, behind the now demoralised Atlantean army. Gosscalt knew there were various defences on the hills near Snattarona, and around Cennatlantis itself, but hoped that his speed of movement would enable him to sweep through these. General Buentel, who now commanded the Atlantean armies on this front, (about 120000 along the Burastoura, with another 100000 facing the Ughans north of Dravidos), was ready for tactical trickery by Gosscalt, and was not taken in by the feint at Yellis, with which the Basquecs began their campaign on March 10th 745. He heard of the main Basquec crossing of the river further north, and rushed most of his forces there to confront it (about 80000 in the end). In the scrappy running battle that ensued, the Basquecs’ advance was halted for a time, but Buentel was unable to force them backwards, and was himself gradually outflanked to the north. Outnumbered as he was, he retreated on March 12th westwards to the Babemme woods, which he thought would make a good defensive position. Gosscalt followed him up with 110000 men, and there followed on March 16th, the Battle of the Babemme. Buentel’s position on the edge of the woods proved nearly impregnable, and Gosscalt soon decided that he must manoeuvre his way past this. He sent cavalry, and small forces of mounted infantry directly south down the main road towards Gilliso, thereby threatening both Buentel’s communications with Cennatlantis, and the city itself. Buentel had foreseen this, and believed that Gosscalt would not dare march much further in that direction, as long as the Atlanteans remained in the Babemme, and threatened the Basquecs’ flank, and communications with Yellis and Atlandravizzi. But the isolated Basquec forces roaming around Gilliso, and even approaching the Snattarona position terrified the government in Cennatlantis, and though Brancerix was certainly willing to give Buentel the chance to stay where he was for a little longer, the Imperial Generalissimo insisted he move back to the Snattarona defences, and protect the capital directly. Buentel accomplished this flank move with great skill on March 20th, and placed his army on the range of hills, already entrenched, which lay north-west of Snattarona. This defensive position had long been the vital one, which protected the approaches to Cennatlantis, and the access to Atlantidieh, from the east. It had played a vital role in 525, when Cenccos and the rebels had unsuccessfully tried to defend the capital against Atlanicerex’s enveloping attack from the east in the First Battle of Snattarona. Again in the Imperialist-Republican wars of the 590s – 620s, this whole range of hills marked part of the boundary between the two sides. Since then, Snattarona itself, and the hills to the north and south had been made into permanent defensive positions, with forts and trenches and gun-emplacements. The Second Battle of Snattarona began on March 30th. Gosscalt planned to strike the main Atlantean position, on the northern range of hills, frontally, and then surprise the enemy by assaulting the southern hills from Snattarona, occupying the top of them, and taking control of the main road to Cennatlantis, which ran in a pass between the two hills. The northern attack predictably failed with heavy loss, and overnight Gosscalt moved much of the assaulting force, plus reserves, (75000 in all), to Snattarona and the woods all round it. Earlier in the day a small force had insinuated its way to the top of these hills, using one of the same paths that Cenccos had over 200 years earlier. Needless to say it ran into a strong fort specifically designed to defend this approach, and could move no further. News of this did, however, alert Buentel, who prepared some 40000 of his total force to occupy these southern hills, in case Gosscalt should try to occupy them, as was indeed his plan. As a result, when Gosscalt’s army swarmed up the northern slopes of this range of hills on March 31st, it soon met Buentel’s force partly in position, and partly approaching from the south. In a fierce daylong battle, the Basquecs slowly forced back the Atlanteans by sheer force of numbers, and seized the top of the hills by early afternoon. Buentel had continually sent more forces to help hold, and then retake these southern hills, but by the end of the afternoon, he realised the game was up, having suffered over 16000 casualties. Still holding the northern hills securely, he withdrew as night fell, and moved to cross the Cresslepp some 20 miles north of Cennatlantis. During April 1st, he completed the crossing and moved south into the Cennatlantis defences. Gosscalt was scarcely aware he had gone, at first, and made no attempt to chase him up, having himself suffered at least 15000 casualties. THE (THIRD) SIEGE OF CENNATLANTIS There now followed something of a panic within Cennatlantis, as citizens and government officers alike tried to flee from what seemed like the imminent capture of the city by the Basquecs. But the Emperor and his immediate colleagues insisted on remaining in the city to set an example, and after the first few days, a military cordon was placed around Cennatlantis, to stop any further flight. Nevertheless, over the next month most government offices were quietly evacuated to Atlantis as the enemy loomed ever closer to the Imperial Palaces and administrative offices north of the city, and the Emperor himself moved back to Atlantis, when it appeared that the city was going to be completely surrounded. In fact this never quite happened, and Gosscalt’s failure to isolate the city during the siege was one reason why he was never finally able to capture it. Nevertheless, the situation was very serious for the Atlanteans throughout the siege, which lasted a year, into 746. For although the Basquecs were just held off at Cennatlantis, other enemy armies continued to press forward on almost every other front for the rest of the year. Cennatlantis’ initial salvation was due to four things: the permanent defences around the city, the reinforcing of the Atlantean army there from the south, the decision of Gosscalt to split up his army east of the Dodolla, rather than pressing forwards with overwhelming force against the city, and his failure to involve much of the Ughan Army in a joint attack. Cennatlantis’ defences had been improved at various intervals since the sixth century, notably the updating of the forts surrounding it to withstand artillery in the 640s and 650s, and the construction of a ring of forts along the Dodolla and around the town, for a circumference of sixty miles or so, during the earlier Third Empire. These forts protected the government suburbs, but did not stretch as far west as the river Gonril. Further defences were built in the few years before the war began, partly to join up the forts, and partly to provide further defences south of the city, down to the Cresslepp. One particular military problem in this area was that the Trannolla Thounca (Marshes) had been drained after 700. These marshes had hitherto covered the whole area west of Lake Trannolla, between the rivers Burtounna, Cresslepp and Dodolla, and seriously constrained any attempt to move on Cennatlantis from the south. In 744 and early 745, cohorts of civilians, as well as army personnel, were mobilised to make Cennatlantis completely impregnable. This involved digging lines of trenches all round the capital, between the forts already there, and the deliberate destruction of the dykes and canals, which had been built to drain the Trannolla marshes. Now at the same time as Gosscalt’s main army had advanced on Cennatlantis from the north-east, a second army moved down the east side of Lake Trannolla. As in the previous year, this army’s task was to capture the hill between the rivers Burtounna and Helvenslepp, and then move on Cennatlantis and Helvris. The hill was duly captured, but then the Atlanteans attacked it again with reinforcements from Cennatlantis itself on March 12th. The Basquecs were defeated at this Battle of the River Burtounna,, and the Atlanteans began to pursue them. However, the defeats north of the lake caused them to halt, and then the shattering defeat at Snattarona led to their immediate recall to defend Cennatlantis – they counter-marched, and arrived in the nick of time. Meanwhile, as mentioned above, Gosscalt had divided his victorious army after Snattarona, sending part of it north to try to move west between the lakes at Gasirotto. As a result, he had only 80000 men with which to attack Cennatlantis initially, later increased to 110000, including a few Ughans. The Atlanteans’ two armies there in the ringed defences were over 90000. Gosscalt’s frontal assaults on various forts and trenches failed during April, with considerable casualties. Thereafter both sides reinforced themselves, and the Basquecs in particular, essayed to get past the Cennatlantis defences, either by attacking up from the south, or round the north from the north-west. The decisive battle occurred on July 12th – the Second Battle of Failrunn. This was an attempt by the Basquecs to completely surround the Atlantean defences at Cennatlantis. It led to a disastrous defeat, and the wounding of Gosscalt himself, when an Atlantean army, which had been stationed around Gentes to the west, preparatory to an attack on the Basquecs, struck the enemy in flank at Failrunn. The planned Atlantean attack followed up immediately afterwards – too soon, as the Atlanteans were held off west of the Dodolla, and forced to retire. The rest of the year on this front was spent in pointless static trench warfare, which served to teach the two sides, that now that both of them were equally well armed, and of similar numbers, the defence, if it used forts and trenches, had become much the stronger. However, to the south of Lake Trannolla, following the retreat of the Atlanteans into Cennatlantis after the battle of the Burtounna, the southern Basquec army was able to advance right up to the gates of Helvris by June. At that point, however, the strength of its defences, as with Cennatlantis, prevented the Basquecs gaining any further ground for the rest of the year. THE VICTORIES OF THE UGHANS The offensive of the Basquecs in the spring of 745 occupied the attention of the Atlanteans, and attracted reinforcements and replacements away from the armies facing the Ughans. There was a total of about six Ughan corps, or 170000 men facing the Atlanteans from Dravidos north up the river Gestes. The Atlanteans had some 140000 men, but many were locked up in fortresses across Dravidieh and Nunchalcrieh. After consultations with Gosscalt, it was agreed that initially the Ughans would protect the Basquecs’ right wing, take Dravidos, and then advance to Micazzo, as well as providing a small token force in the Basquec army attacking Cennatlantis. Further north, the Ughans had their own agenda, which involved moving into the Diefillen woods, and up the river Merros, seizing the fort of Fembepand, partly in order to broaden the front of their attacks on Gestskallandieh. The Ughans’ plans for the campaign turned out very successfully, and this year certainly represents the highest point of their war-effort. In March, 80000 Ughan surrounded Dravidos, and besieged the garrison of about 25000. Soon after, another army crossed the Gestes near Pand-aneyu, and advanced up the Merros. The Atlanteans had hardly any mobile forces in this area, and were unable to prevent the Ughans moving north to besiege Fembepand. This siege dragged on, however, because the Ughans kept withdrawing forces from the besiegers to join the battles against Gestskallandieh. It was not until July that the fortress fell, and thereafter the Ughans moved leisurely north through the Diefillen across the border with Gestskallandieh. The siege of Dravidos lasted some time, too, but the main Ughan army soon left it to rear and moved to occupy Dravizzi. Dravidos finally fell in June, and six weeks later, the Ughans moved towards Micazzo. However, the Atlanteans had built up their numbers by now, and threatened the Ughans’ right flank from the Chalcran Forests. After a series of skirmishes and small battles, both sides retreated. After this, the Ughans made no further attempt to take Micazzo, but spread out their forces across the north-east, taking Bemmetisso and Balbemme, though the latter was later retaken by the Atlanteans. At the same time, Ughan armies of over 160000 were invading Gestskallandieh, and forcing back their enemies, who had about the same number of troops. Again, though, by the autumn, the Ughans’ advance had been halted.

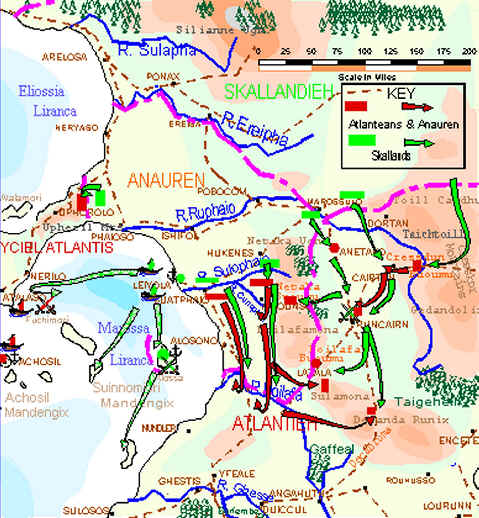

SKALLANDIEH ADVANCES ON LAND AND SEA Skallandieh began the campaigning season of 745 with as successful an attack on the Atlanteans as the Basquecs and Ughans elsewhere. The Skallands left alone the front west of the Netaka Mountains, where the two sides faced each other across the river Sulophaio, the Atlanteans and the remaining Anauren forces having the strong fortress of Amounoso to rely on. Instead they opened a new front to the east, moving through the passes of the Cresskor Mountains to surprise Cairtan in April, as well as making a frontal attack on the strong fortress of Anetako, which defended the low ground between the Netaka Mountains to the west and the river Ruphaio and the Cresskor Mountains to the east. Anetako was soon surrounded, and surrendered after a siege of two weeks. An Atlantean army, which was to have relieved the fortress, lay to the south, where it was immobilised by enemy attacks from the east. In these mountain passes, the Atlanteans had very few defences, and the Skallands pressed back the Atlantean army into the lower and more open country to the west. Another army then joined the attack from west of the Netaka Mountains, and the two combined, turned the flanks of the Atlanteans, and decisively defeated them on May 2nd, at the Battle of Runcairn. After this, the floodgates opened, and Atlantis suffered such a run of defeats as seemed to threaten in the end the very existence of the Province of Atlantis, and the whole west of the Empire. The Skallands advanced south through Runcairn, completely turning the lines on the river Sulophaio, though fortunately for the Atlanteans, a range of mountains, the Netaka, separated the two theatres. By July, the Skallands had reached the hills of the Decanda Runix, and were trying to cross the pass called the Decabrumu. If they succeeded, they would reach the rolling open country around the river Rollepp, and could then move either west on Atlantis, or south on Cennatlantis. But the Atlanteans managed to block this pass in time.

The Skalland advances during 745

To the west, the advancing Skallands threatened the eastern flank of the Atlanteans on the river Sulophaio, through the Netaka Buoumu (Pass). Encouraged by a frontal attack as well, the Atlanteans had to retreat back to the river Noilafa, where they were for the time being able to protect their eastern flank from attack through another pass, the Noilafa Buoumu, by holding the fort of Latala. But, apart from Latala, the Anaurens and Atlanteans had now been ejected from the whole of Anauren, and were on the borders of Atlantis itself. Temporarily stymied here, the Skallands now tried a direct attack on the Province of Yciel Atlantis, across the Upheril Mountains. This position was immensely strong, however, and the Atlanteans were able to hold off the attack at the Battle of the Upheril Mountains. At the same time as they were winning these victories on land, the Ughans were exploiting their strength at sea. During the year, their new navies gained control of the Marossa Liranca (Bay of Marossan). They took over the former Anauren naval base in the Suinnomiori Isles, and then sent out a series of naval and amphibious expeditions towards the other islands in the Bay, which were nearly all Atlantean possessions, but with small or no garrisons. The nearest Atlantean naval base was at Achosil, and the navy here contented itself for most of the year with fending off a series of attacks on the islands nearby. One major amphibious expedition tried to effect a landing near Nerilo on the southern coast of Yciel Atlantis, but the landing was decisively defeated after the fleet was forced off. Nevertheless the Skalland moves to the south were more successful, and by the end of the year, Skalland garrisons had been placed on all the important islands of the Bay, including those lying off Nundler, which was only 70 miles north of Atlantis. THE GREAT BASQUEC NAVAL EXPEDITION TO THE HELVENGIO South of the Helvengio, the war continued. In Marossan, neither side made much progress, despite a number of attacks by both sides, and at the end of the year, the armies were in almost the same places as they had been at the start. Further south, however, Basquec troops continued to advance slowly southwards from the river Gosal. But additional attempts to seize the Siphiyans Mountains, which would leave the Atlantean port of Siphiya at their mercy, continued to elude the Basquecs. In the far south, the Basquecs were more successful. They made further raids against the inlets and estuaries of Rabarrieh’s coast, and, having defeated its navy the previous year, were able to blockade most of its ports on the Eriphicko (Southern Sea). The most spectacular Basquec success at this time was a naval one. The Basquec navy, having defeated the Rabarran navy the previous year and blockaded its survivors in port, now faced up to the Atlantean navy in these waters, based at Siphiya. This force was in a perilous position in early 745, with Basquec armies threatening to take the port from the north, the Basquec navy hovering near the Siphiyan islands, and no hope of Atlantean naval reinforcements, because of the threat posed by the Skalland ships in the north. On the other hand, the Basquec navy could not actually harm the Atlantean navy at Siphiya, protected as it was by a maze of fortified islands, booms, and primitive minefields. But the colony was very nearly cut off from Atlantis itself, the only contact being by a difficult land route along the coast to the west, and from occasional naval convoys from Atlantis. The Basquec admiral, one of the boldest seamen of the War, now saw a chance of defeating the Atlantean navy, taking control of the whole Eriphicko, and threatening not just Siphiya, but the western coast of Th. Thiss. too. In April he moved the Basquec navy north to threaten the approach of the Atlantean supply convoy from the direction of Th Thiss, which he knew should be due to arrive shortly. Hitherto these had come with minimal naval protection, and usually with some of the Siphiya force emerging to protect the convoy for the last part of the journey. On these occasions, the only threat had been from one or two Basquec raiders. This time the convoy, which was indeed on its way, was threatened by the whole Basquec navy. As the Basquecs had anticipated, most of the Atlantean navy emerged to guard the convoy, and the Basquecs had the chance of forcing a decisive sea-battle. The Atlanteans were outnumbered and out-manoeuvred. Moreover, new technology was beginning to make its mark. Both sides now had all their main ships armed with very heavy cannon, and increasing numbers on both sides were ironclad. Finally, steam had arrived, and by now most ships were steam-powered. The battle, called the First Battle of the Siphiyan Islands, was an overwhelming Basquec victory. Many Atlantean ships were sunk or captured, and the rest fled back to Siphiya. The convoy, though damaged, managed to flee to an Atlantean port and colony some miles down the coast to the west, and its provisions reached Siphiya overland. Over the next months, the Atlanteans were firmly blockaded in port, and a landing was made west of Siphiya, which completely now cut it off from contact with the outside world. Then, in July, frustrated by his attempts to take Cennatlantis or Helvris, and unable to take control of the Helvengio, because of the presence at Giezuat of a sizeable Atlantean naval force, Gosscalt was stuck by an idea. It can be viewed as either a stroke of genius, or a harebrained folly; it was called both at the time, and has been ever since. His plan was that the Basquec navy, or nearly all of it, now in control of the Eriphicko, should sail out westwards, up the coast of Th Thiss, seize control of the forts guarding the entrance to the Helvengio, and enter it, defeating or eluding the Atlantean navy based at Giezuat. It should then help to transport an army from Noehtens to Giezuat, using transports hitherto blockaded up the river Gairase. It would take the island, then land on the shore near Helvris – or perhaps further west. Meanwhile, the Basquec navy would re-emerge from the Helvengio, and prevent or defeat any Atlantean attempt to move naval forces down from the northern bases to the Helvengio or the Eriphicko. Combined with further land attacks, the Atlanteans should then realise they were facing utter defeat, and sue for peace. The whole scheme was obviously extremely risky, and could be ruined by any number of things going wrong. In particular, it would leave the Eriphicko empty of Basquec forces, save for a token force blockading the Atlantean and Rabarran navies in port. Nevertheless, egged on by Gosscalt, it was organised and the expedition set off in October. Determined to be in at the kill, Gosscalt himself left the central front, and betook himself to Noehtens. The fleet, meanwhile, successfully made its way round and up the coast of Th Thiss., though not without the Atlanteans learning of its approach. The Basquec Admiral had anticipated this, and hoped that it would encourage the Giezuat fleet to come out of the Helvengio to face him – thus making it easier for him to slip in. To further lead the Atlanteans on, he did not take the fleet straight to the entrance of the sea, but carried on north, as if to threaten Atlantis itself. The Giezuat navy took the bait, and hurried out to protect Atlantis, which actually had virtually no naval protection of its own, although the main Sulosos navy was on alert just to the north of it, having to look in two directions at once, north to the Skalland navy, and now south to the potential new Basquec threat. The Basquecs did not intend to fight the Atlanteans head on; instead they sailed round them, and pausing only to drop off a small landing-force at Miolrel, entered the Helvengio. Hastening eastwards, the by now bedraggled fleet moved to the port of Giezuat, which promptly surrendered, amazed at the apparent disappearance of the Atlantean navy. Meanwhile Miolrel had fallen to the Basquecs (though no attempt was made to take control of the Nosinge peninsula to the north). The Atlantean navy outside the Helvengio, having beaten a small Basquec diversionary force, now tried tentatively to re-enter the sea, but was beaten back by the Basquec navy and the land batteries now under Basquec control. In the Helvengio, a delighted Gosscalt now watched his troops sail unopposed from the Gairase to Giezuat island. For a brief moment, now, Gosscalt imagined his daring plan had worked. He ordered his land armies to make new attacks on the Atlanteans, and encouraged the build-up of forces on Giezuat, preparatory to an invasion of the Helvran mainland. He also sent out a suggestion to the Atlantean Government that it might like now to consider an armistice and peace negotiations – on Basquec terms, naturally. Then it all collapsed, like a pack of cards. The Atlantean fleet outside the Helvengio was now reinforced by additional ships from Sulosos, and again tried to re-enter the Helvengio. This time, in late November, mid atrocious weather, it succeeded, as the Basquec fleet was scattered for miles around. The Basquecs, depleted by the journey, storms, and ships dispersed to Giezuat and the Gairase, were beaten in a battle to the west of Giezuat. Forced to flee, most of the navy abandoned the Helvengio altogether, and hid in the Gairase estuary, where it was shortly to be blockaded. The troops already on Giezuat island, over 15000, were thus abandoned and cut off. The year ended with an Atlantean army landing on the island; shortly, it would defeat the Basquecs, and force them to surrender. It was also only a matter of time, before the Atlantean and Rabarran navies, blockaded in the Eriphicko by a token Basquec navy, shorn of the majority of its forces which had disappeared forever into the Helvengio, realised the new situation, and emerged again to seize control of the seas. To read the next part of this history, click on (4) 746-747 |