|

Home Page

Discovery of Atlantis

First Empire-(1) to 261

Second Empire- (1) 361 - 409 |

|

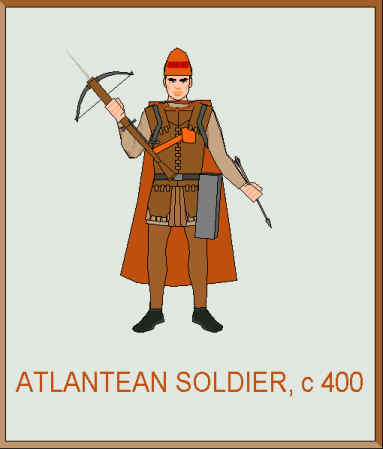

2. The Atlantean Army during the Second Empire, 361 - 585 The basic structure and organisation of the Army during the Second Empire was laid down, as we have seen, in the last years of the First Empire. From 290 there existed the "College of Military Art", which was responsible for the study of military tactics and strategy and the improvement of the Army. Since the early fourth century, the conduct of wars came under the control of the Imperial Council of War, under the overall supervision of the Emperor. After 391 this was reconstituted as the Grand Military Council. This included the Emperor, members of the College and any relevant Provincial Military Governors. These Military Governors, one in each Province, took direct administrative control of the armies based in that Province during wartime, but he would not become the commander-in-chief, unless there was an emergency - the Emperors had had enough of independent and rebellious Military Governors during the Imperial Wars from 353 to 361. This method of overall control could become cumbersome, but usually the Emperor himself was able to provide a unity and driving force behind it all. It should be noted that it was unusual throughout this period for the Emperor himself to go into the field with the armies, though there were exceptions - Atlaniphon II, Atlanicerex in the Great Civil War, and later Crehonerex III at the time of the Revolution. THE STRUCTURE OF THE ARMIES After the Empire reached its final borders, more or less in the time of Atlaniphon II, Armies were situated in all the frontier Provinces, and some interior ones. Depending on the threat from outside the borders, several Armies might be placed in a Province. Armies (PUEGGISIX) numbered about 9500 men each in the "classical" period, about 380 - 480, each consisting of ten OCHOSIX of 800 men. These were subdivided into units of 80 men (PUONDIX or Hundreds) and then to 8 men (DOULIX or Tens). The OCHOSIX were normally 8 of infantry and 2 of cavalry, plus attached artillery (torsion) and mounted infantry. The Armies were all numbered within each Province, and known, as a group, as the "....Provincial Army", commanded by the most senior General of these Armies. If a campaign involved several Armies, then these would be grouped together as an "Imperial Force", and placed under the command of the most senior Army General . After 480, in the so-called "Romantic" period, a PUEGGIS, still about 9500 men, was increased to 12 OCHOSIX, which according to the new tactical doctrines, could act more independently. During this period, too, Provincial Army Reserves were formed, to act as purely defensive forces against invasion (as in the Third Ughan War and the various incursions of the barbarians). After 540, until 587, this reorganisation was settled as 6 OCHOSIX in the Reserve Force, and 8 in the main PUEGGIS, making a total of 11500. In addition Local Forces were raised to help frontier defence, for example in Th. Thiss, Manralia, and the Keltish Provinces. WEAPONS AND TACTICS - THE CLASSICAL PERIOD The backbone of the Atlantean Army was the bayonet-crossbow ("Bourtourtso" in Atlantean) - this weapon was made of steel. Swordsmen were still retained, though in decreasing numbers, until 450, when they were finally done away with. Initially the crossbow men occupied a central bloc in each OCHOS, with bowmen on either flank, so that each gave the other mutual support. After about 420, when the proportion of swords to bows had fallen from one third to one fifth, the swordsmen were deployed behind the bowmen, from where they could come forward in the attack, or defend the rear and flanks against attack. As far as the bowmen are concerned, they used either light or medium crossbows, the former being quicker to reload ( 3 times a minute, as opposed to 2 1/2) but firing a lesser distance (250 as opposed to 300 yards). Reloading was carried out by means of an intrinsic steel lever in the case of the lighter crossbows, and with windlasses for medium ones, and also for the mechanical crossbow type of artillery. Heavy artillery (catapults) were an army reserve, though horse artillery was invented by 450, and could be attached to the mounted infantry. In the classical period, the Atlantean Army used strategy and tactics worked out in advance in great detail. The Armies advanced steadily on the enemy, stopping to fire at intervals, along with any artillery, the range of which was not much greater than that of the crossbowmen. The infantry was arranged in three ranks, firing alternately. In the end, the infantry would charge with the bayonet. An OCHOS of medium cavalry was attached to each PUEGGIS, and it would defend the infantry against enemy infantry attacks, especially if using swords, or against cavalry. If the infantry were attacking, it would wait until the infantry had softened up the enemy with their missiles, then join them in a devastating charge. Mounted infantry would already have been sent on ahead to seize important tactical features, such as hills. Light cavalry, armed with bows and arrows, would skirmish ahead and on the flanks. The soldiers had gradually done away with armour in the later 300s, until by about 420, they wore thick leather jerkins, with just metal protection for their breasts and heads (in the form of helmets). In some ways, they were vulnerable both to the arrows of enemy bowmen, and the swords of enemy swordsmen (which could be superior in strength and size to Atlantean crossbow-bayonets), but their disciplined organisation, marching and firing, plus the protection provided by cavalry and artillery, meant that they usually beat all their enemies, at least in the 400s. Indeed the Atlantean Army was superior to nearly all its enemies at this time, in every respect. The Ughans were the only serious enemy of Atlantis, and they initially had only a small Royal standing army, with a lot of unreliable noble feudal levies. Arms consisted of swords and pikes. After contact with the Atlanteans, the central Army became stronger and more reliable and was increasingly armed with bows or crossbows. But there was little armed conflict between Atlanteans and Ughans at this time. Other enemies consisted of nomadic or semi-barbarian tribes around the periphery of the Empire, and these could easily be dealt with by the Atlantean frontier defenders, infantry and cavalry. ROMANTIC PERIOD TACTICS The title of the so-called "Romantic" period really relates, of course, to the contemporaneous change from Classical to Romantic style in the arts and in philosophy. What it refers to in the military sphere is, generally speaking, a loosening of the fairly rigid standardised make-up and combined action of the Atlantean Army, as it had become over the past century. Specifically, individual PUEGGISIX and OCHOSIX were given more independence in action; commanders were encouraged to create surprise by their strategy; the use of regional and local forces was encouraged; and the current defensive-minded attitude of Atlantean commanders was halted in favour of a greater offensive-mindedness. Tactically, the cavalry was released from close co-operation with the infantry, and encouraged to scout out way ahead, or concentrate on the flanks against enemy horsemen. This was all possible because the Empire was virtually free from serious attacks from abroad, at least till the 520s. The new doctrines were successfully tried out in various small campaigns against unruly tribes in the south (around 500), pirates on the southern seas (480s), revolts amongst the North Kelts (500), and the Raziran rebellion of 500. A particularly good example of this strategy can be seen in the campaign and first battle of Snattarona in 525, during the Civil War.

THE FIRST BATTLE OF SNATTARONA, 525 Following their seizure of Cennatlantis, a rebel force of seven Armies, led by Cencos, advanced over-confidently northwards up the Snattarona road to seek the Emperor (shown by the light blue movements on the map). Atlanicerexĺs forces were collecting in the Crolden Hills, and then moved southwards. The Emperor and his military advisers now planned a typically "Romantic and exuberant strategic manoeuvre to trap and wipe out the whole rebel force, retaking Cennatlantis at the same time. Atlanicerex moved four Armies on down the road from Snattarona in the afternoon and evening to face the rebels, while two lots of outflanking forces were sent off through and behind the hills which at this place hemmed in both sides of the main road. Two Armies plus cavalry moved across the hills to position themselves on the right flank of the enemy, who had four Armies deployed across the valley during the night. Three other Armies moved more widely, and by 10am were to the right of the rear rebel Armies (shown by the mauve movement markings on the map). As the main Atlantean force advanced frontally against the rebels, to "fix" them, the first flanking force poured down the slopes and smashed into the flank and rear of the rebel right wing. Soon after, the other force attacked the rebel rear, with one Army moving far behind it to cut the road back to Cennatlantis. The battle was soon over. The rebels fled off to the west, leaving their commander dead on the battlefield, while the Loyalists moved directly on down to take the capital. This clever example of the new, vigorous strategy cost the Emperor only 2000 casualties, while the rebels lost 10000 or more. THE THIRD UGHAN WAR AND THE RETURN TO DEFENSIVENESS Even prior to the Third Ughan War of 536 - 539, increasing pressure by barbarians in the north-east required a greater commitment to fixed defences by the Atlanteans. But the Third Ughan War, with the serious defeats dealt to the scattered Atlantean forces by the newly resurgent and strongly centralised Ughan forces, led to a rapid rethink of their strategy by the Atlantean generals. The War was won largely because the Ughans, having defeated the weaker Atlantean forces in the open field, were halted by the last-ditch defences of several fortresses in Chalcr´eh. Without gunpowder artillery, fortresses of any nationality were almost impregnable in this period. Following the War, Atlantis realised that the Ughans had reached parity with the Atlanteans so far as weaponry and army organisation was concerned, and the same was likely to be the case in a war with any other major state ( e.g. Basquec´eh). The Romantic doctrines were now thrown out, and a defensive mentality took over, both in wars with major states and against nomads on the borders. Fortresses were strengthened, Atlantean armies were encouraged to dig in and use entrenchments (and armour was reintroduced for infantry), while armies were put back under tighter central control. Firepower became the watchword, making use now of a somewhat heavier form of light crossbow, with a greater range - and bayonet-attack style advances were frowned upon. Cavalry was restricted to operations against barbarians, while artillery was much increased in number and also somewhat in power.

The fortress of Dravipand on the river Gestes, the border with

the Ughans,

This doctrine met its nemesis in the Basquec War of 582-586, when the Atlanteans, as the attackers, were held up and bogged down in front of strong Basquec fortresses, and most spectacularly in the fighting against the Revolutionaries after 587, when the latter's fast-moving, loosely organised forces completely outmanoeuvred and out fought the slower and much more cautious Imperialist armies. Over the next decades, the Atlantean Army metamorphosed into something very different from its Second Empire self. To conclude, however, and as a memorial to the Second Empire Army at the height of its might, here is the text of part of a letter written by the poet Normell´el, who accompanied Atlaniphon II on his campaign against the Ughans in the Second Ughan War, and witnessed the climactic victory of the Atlanteans at the battle of Yrullia in 441.

THE BATTLE OF YRULLIA - an eye-witness account (part) by the poet and dramatist, Normell´el. All references in the first person in the original would really have been in the third person, of course. A map of this battle, with the positions of Normell´el and the Emperor is given after the account below. .... "In this position behind the centre of the battlefield, just behind the main front line of our troops, the Emperor, his staff and myself had a superb view of the enemy army about half a mile in front. There they were, the Ughans, row upon row of them, wearing costumes of all types, and all in front of me were on foot, except for a few wandering to and fro on horseback within their ranks. These I took to be their officers. As far as I could see, they were nearly all armed with swords, though I saw some with bows and arrows. Later it turned out that quite a number actually had crossbows, like our men, though inferior ones. The enemy were on a hill in the centre, but their two wings, as I saw them at that time, were on level ground like ourselves. There was a river to our right, and the Ughans had already crossed it, seeking presumably to approach our right flank, using its protection. Some of our troops were already skirmishing with theirs over there, however. "Our party moved over a little towards out left, and then the generals around the Emperor suddenly exclaimed and pointed. I looked, and there was a long line of our men advancing through the low undergrowth up a hill on the right flank of the Ughans. Streaming past them, overtaking them, and swarming up the hill, I saw our cavalry and mounted infantry. What happened next over there was difficult to make out, but obviously enemy forces were encamped upon that hill, and fighting for it continued for some time, though our men eventually seized it. This drew the enemy's reinforcements away from his centre, as I later gathered - all part of our generals' plans of course. "But now my attention was drawn to the other side of the battlefield, our right, as masses of Ughan infantry were running and howling across the ground in between onto our right flank men. Our forces stayed there quietly and unmoving to receive them, while the great catapults in front of our centre turned to face the enemy, and waited patiently till they were in range. Once they were about a quarter of a mile away, they began firing furiously, and many an Ughan was transfixed by one of our huge crossbow bolts, or crushed with his neighbours under a stone of perhaps 100 lb., hurled at him by our catapults. "Soon after this, as the enemy came ever closer to them, I saw officers cry out to our men facing them, and suddenly the front rank of parts of the OCHOSIX knelt down and levelled their crossbows, while the two rear ranks fired above them. A volley shot off, and hundreds of yards away, a line of Ughans rushing forwards, faltered and fell. These men reloaded, and others now aimed and fired. So it went on, and more and more enemy fell, and yet they still came on. Finally they reached our line, who faced the enemy's swords with their own bayonets. An indescribable scrimmage ensued, but it was always possible to distinguish the two sides by their dress. The Ughans, as I have said, wore a great variety of barbarian clothes, but our men were all in uniform. Their tall oval hats towered above the melee, while their bodies, protected by no armour nowadays, were covered in their tunics, with the belt at the waist, fastened to which were the arrow quivers, and the diagonal belt higher up, and a large leather boss over their hearts. "The Ughans seemed to be prevailing, and forcing our men back, when lo - round the right by the river marched, at high speed, our reserve infantry, smashing into the Ughan flank. And again past them, suddenly there streamed our cavalry from the rear, wielding their swords, and crashing into the Ughans' flank. The Ughans were beaten - they turned and fled -... - but the battle was far from over yet..." To read the next part of this history, click on The Army- 585 - 740

|